From Pacific saury to seaweed to shrimp, ocean warming stemming from climate change is having an adverse effect on marine species all over the world.

The impact in waters around Japan is showing up in myriad ways: decreased sizes of species including mackerel and anchovy in the country’s typically rich eastern coastal waters, a dramatic drop in konbu (kelp) yields off Hokkaido and an increase in hybrid species of pufferfish, posing concerns for catches of the delicacy.

The issue is likely to become more pronounced as warming continues — ocean temperatures are rising four times faster now than in the late 1980s, a recent study by the University of Reading shows.

And yet, seafood is a vital part of the Japanese diet and a crucial source of sustenance for billions around the world.

On the whole, it’s also more environmentally friendly than land-based animal proteins like beef, pork and even chicken, while seaweed is potentially a major carbon sink, making the industry an important part of decarbonization efforts.

Faced with these challenges, researchers in Japan aren’t sitting still.

At home and abroad, a series of aquaculture projects are underway that aim to improve the sustainability of aquaculture and boost production even against the strong current of climate change.

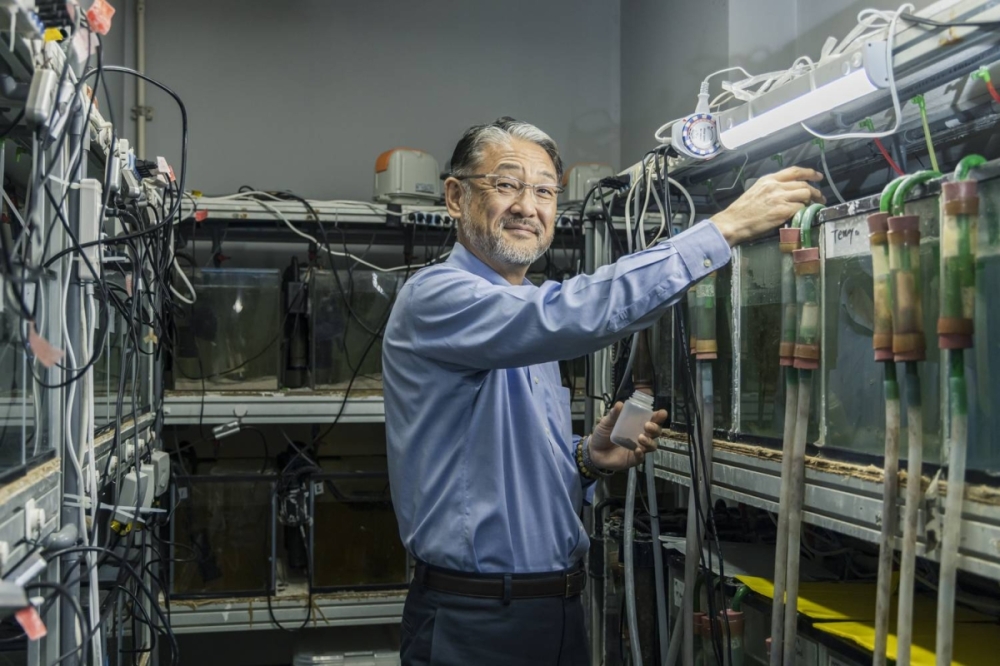

“The natural stock of fish and shrimp is not increasing and may be decreasing due to climate change and overfishing and some pollution of the environment,” says Ikuo Hirono, a professor with the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology. “However, the world population is increasing, so we need more and more animal protein sources.”

Invasive fish

While seafood produced through aquaculture compares favorably with beef, poultry and pork in terms of emissions, the industry still accounts for 0.49% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2020 study in Nature.

Not all types of aquaculture are climate friendly, either. Farmed shrimp, for example, produces 12 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent for each kilogram of food — less than a quarter of that produced by beef production but double that of poultry. There are also concerns about pollution via fish farms, as nutrient-rich water that leaks from them into the natural environment can cause severe ecological damage.

Even with those issues, there’s little hope of reducing reliance on aquaculture, particularly in tropical nations. A separate study published in Nature in 2020 shows that the catch potential in some tropical exclusive economic zones is expected to fall by as much as 40% by 2050 from the 2000s under an extremely high emissions scenario, due to warming, a reduction in the ocean’s pH level, deoxygenation and sea-level rise.

With aquaculture making up over half of all seafood production, the impetus to improve sustainability is clear.

Since 2019, Hirono has helped spearhead the Thai Fish Project, an initiative funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Japan Science and Technology Agency that aims to boost the sustainability of aquaculture in the Southeast Asian nation.

It’s not a small undertaking — in 2019, Thailand ranked 10th in the world in aquaculture production in 2022, making the sector an important part of the country’s economy. Seafood is also a key food source in the developing nation, with 56% of Thais saying they eat fish one to four times a week, and another 19% five or more times a week, according to 2023 data from Statista.

But all of that production has come with a major drawback: invasive species.

Thai fish farms have typically raised tilapia, a fish native to Africa, and whiteleg shrimp, which comes from South America, both of which are among the most farmed species in the world, according to Hirono. Tilapia is popular as a farmed species in part because it can be raised in freshwater, making it possible to convert agricultural land into aquaculture ponds. Whiteleg shrimp, on the other hand, are omnivorous, making them cheaper to feed, Hirono says.

The potential for specimens to escape into the wild poses a threat to natural ecosystems. A report by researchers involved with the Thai Fish Project noted that whiteleg shrimp has been found in Thai waters since it was introduced to the country through aquaculture in the 1990s, causing the spread of an exotic pathogen and increasing competition with native shrimp species.

“Some of the tilapia and shrimp escaped from cultured ponds and they already reproduced in nature,” Hirono said. “Such an escaped alien species gives a lot of negative impact to the native species.”

Hirono added that, at the government level, there are no plans to curtail production of these species despite the mishaps, because the industry is simply too important for food security and the economy.

So Hirono’s project decided to focus on raising species native to Southeast Asia, namely Asian seabass and banana shrimp. The overarching goal is to improve productivity while employing sustainable practices that limit the impact of infectious diseases and preserve the natural environment. The initiative also promotes the education of young researchers with an eye toward the future.

The challenges with raising Asian seabass had been finding the right feed and solving issues related to breeding.

So far, the results for the project, which was due to wrap up in 2025 but was recently extended for another five years, have been promising.

Scientists successfully developed a new type of seabass feed to lower costs while also making the fish more nutritious for consumers. It’s also passing taste tests and is gaining interest for its commercial potential among Japanese businesses, according to JICA.

For banana shrimp, researchers have achieved artificial insemination, which is necessary to make genetic selections to improve growth and disease resistance. This posed a significant hurdle because the species is highly sensitive to changes in its environment.

In the area of disease prevention, the researchers have also developed new vaccines for seabass and have found certain microorganisms that have benefited the shrimp.

Now, part of the project’s focus is about scaling up their innovative techniques, including by bringing their know-how to other countries in the region.

The populations of Japan and Thailand are graying, but many Southeast Asian nations are seeing growth. “After we develop our technologies, we can introduce the seabass and banana shrimp to not only Thai farms, but also (farms in) Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Laos and Myanmar,” Hirono says.

Vegetables of the sea

It’s not just the ocean’s protein sources that are under threat from climate change. Seaweed, a key part of the Japanese diet and a primary food source for many fish as well as marine mammals like the manatee, is being impacted by rising water temperatures and ocean acidification — a gradual reduction in the pH level of the ocean, caused primarily by the absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere.

Essentially, warmer oceans risk becoming deserts, devoid of the nutrients needed to support seaweed growth.

Seaweed is also a major carbon sink, although some researchers have warned that it’s not a silver-bullet solution and its support of other marine life may actually increase emissions on the whole.

Already in some parts of the world, kelp forests — rich ecosystems that are important drivers of marine biodiversity — are disappearing. According to agriculture ministry statistics cited by the Yomiuri Shimbun, seaweed production in Japan fell by as much as 70% over three decades to about 60,000 tons in 2022, in part due to sea-temperature rise.

With the ocean no longer providing a reliable environment for cultivation, multiple Japanese projects are looking toward land-based solutions and growing seaweed in large tanks where water conditions can be carefully controlled.

Last month at a meeting of international participants in the upcoming Osaka Expo, a project by KaisouLab was highlighted as a “Best Practice,” an expo program that highlights solutions to important global issues.

The project, based in Tokushima Prefecture, aims to tackle the twin issues of high costs associated with land-based farming and limited cultivation periods by combining two species of seaweed — aosa (green seaweed) and akanesou (red seaweed) — to form one that can be harvested year-round. Employing biotechnology techniques and observations from the natural world, researchers have developed a new method of growing seaweed that is less susceptible to environmental changes.

In 2023, the method obtained organic certification from the government-run Japanese Agricultural Standards.

“We believe that this method is a system that can be used anywhere in the world, as long as there is easy access to water from the surrounding seas,” Hirofumi Yamamoto, a professor at Tokushima Bunri University and a research adviser for the project, said during a presentation at the Osaka Expo meeting.

“We hope that this technology will be deployed worldwide, so that we will be able to provide safe and nutritious food to children all over the world,” he said.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.