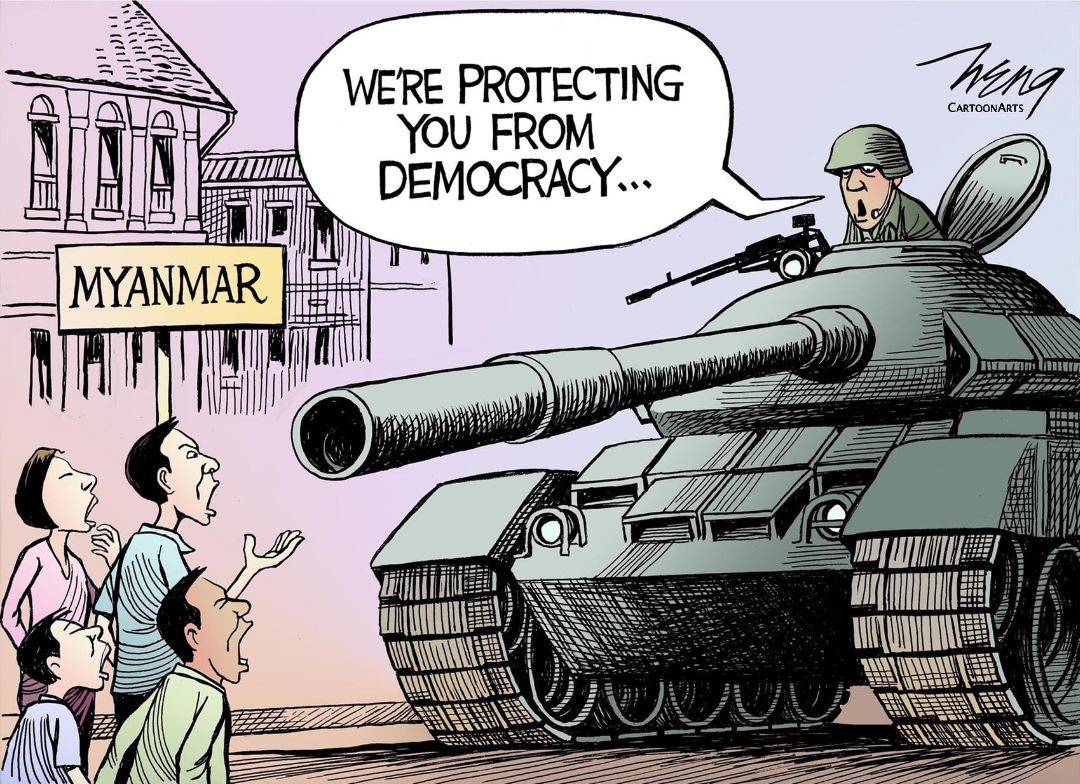

Myanmar has a history of coups and long periods of military rule. The depth, size and persistence of the protests means a return to civilian control of the government is not an impossibility, but the legacy of past military brutality means indefinite junta rule is also possible.

The Tatmadaw, as the military is known, may have been motivated to act on the fear that Aung San Suu Kyi would use her massive re-election in November to consolidate her party’s political position and exorcise the military’s dominance from national affairs. Its timing may have been influenced by other countries’ preoccupation with the pandemic and the global democratic recession, including in Thailand next door where the generals have successfully institutionalized post-coup military control.

Who can fill the leadership gap? The coup presented U.S. President Joe Biden with an early foreign policy crisis and also thrust Myanmar to the center of the intensifying Beijing-Washington geopolitical contest. For the West, support for democracy and human rights in Myanmar is a low-cost exercise in virtue signaling.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.