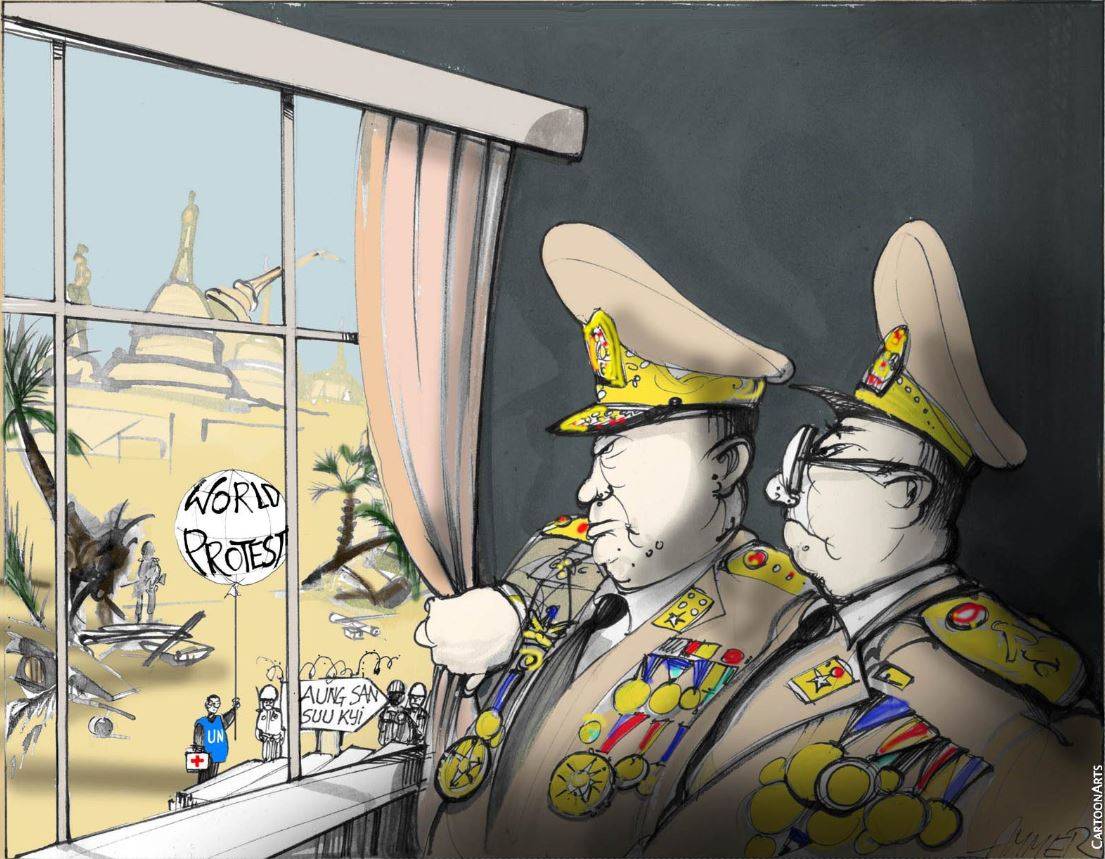

Directly or indirectly, the military has always called the shots in Myanmar. And now that it has removed the decade-old facade of gradual democratization by detaining civilian leaders and seizing power, Western calls to punish the country with sanctions and international isolation are growing louder. Heeding them would be a mistake.

The retreat of the “Myanmar spring” means all the countries of continental Southeast Asia — Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Myanmar — are under authoritarian rule, like their giant northern neighbor, China. More fundamentally, the reversal of democratization in Myanmar is a reminder that democracy is unlikely to take root where authoritarian leaders and institutions remain deeply entrenched.

Given this, a punitive approach would merely express democratic countries’ disappointment, at the cost of stymieing Myanmar’s economic liberalization, impeding the development of its civil society, and reversing its shift toward closer engagement with democratic powers. And, as in the past, the brunt of sanctions would be borne by ordinary citizens, not the generals.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.