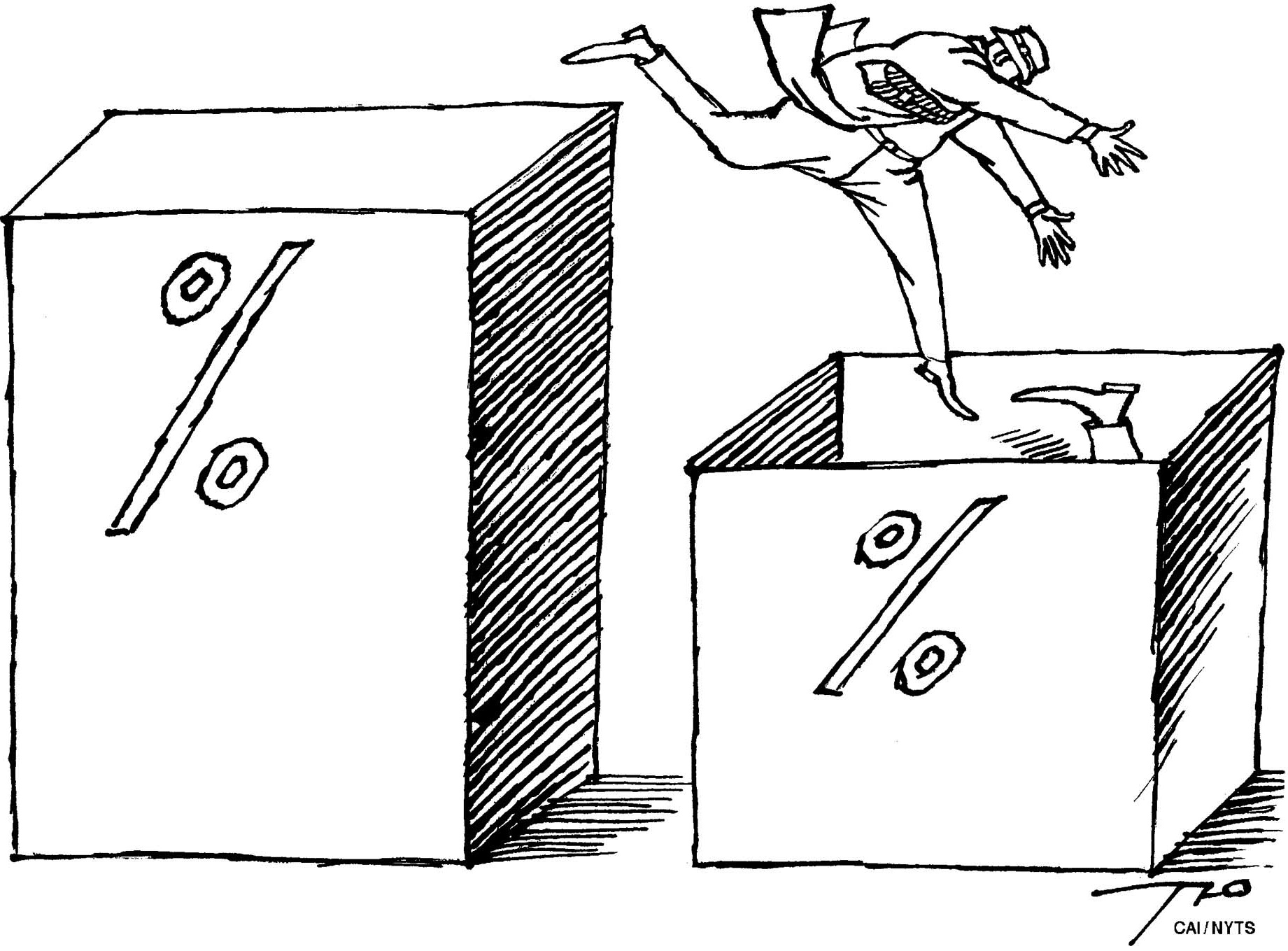

Ever since major central banks cut short-term interest rates close to zero in autumn 2008 and subsequently purchased huge volumes of bonds as part of their quantitative easing operations, economists have debated about when and how fast the "exit" from these unorthodox monetary policies would be.

But, a decade later, developed economy interest rates are stuck far below pre-crisis levels and likely to remain so. Germany's ten-year bond yield of minus 0.02 percent (as of March 23) signals market expectations that the European Central Bank will maintain zero policy rates not just until 2020 (the official ECB forward guidance) but to 2030. Japanese bond yields imply zero or negative interest rates for even longer. And while 10-year yields in the United States and the United Kingdom are just above 1 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively, both of these suggest minimal or no increases in policy rates for another decade.

The 2008 financial crisis may have inaugurated a full quarter-century of dramatically lower interest rates. In this new normal, still more unorthodox policies — including forms of monetary finance — may in some countries be needed to maintain reasonable growth.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.