If parties of the left cannot appeal to the working class, what's their use? The 21st century may be the one in which the umbilical link between the main left parties and organized labor is broken in favor of a politics of identity, and a grasping after some form of direct democracy that translates desires and frustrations into instant policies. Lurking over this movement is the fear of such an unsustainable politics producing authoritarian leaders, especially if the Western economies worsen.

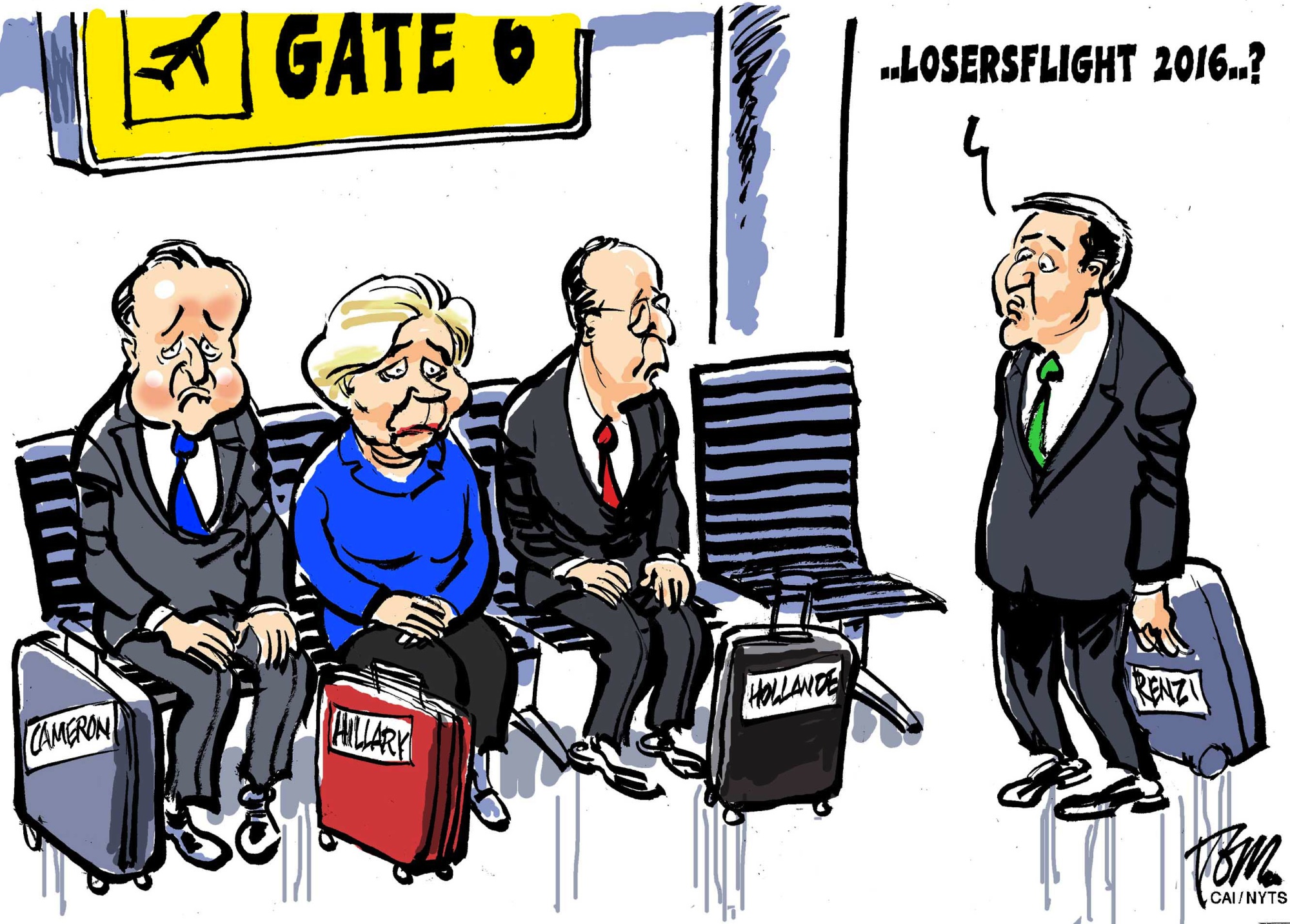

The first week of December saw two leaders of the European left — Prime Minister Matteo Renzi of Italy and President Francois Hollande of France — forced to admit defeat and to leave the political scene, their reputations and policies shredded, their parties embarrassed by their very presence. In Italy, Renzi announced his resignation after losing a referendum on constitutional reform. In France, Hollande bowed to his nation's unchanging contempt and announced that he would not seek the presidency for a second time — an unprecedented move in postwar France.

Hollande, who came in on a rhetorically leftist platform of "hating the rich" was forced to discreetly drop plans to raise their taxes to a marginal rate of 75 percent on annual incomes of more than €1 million. It was actor Gerard Depardieu who called Hollande's bluff most dramatically — by moving across the border into Belgium. Depardieu remains a working class hero. The president who tried to take money from the few rich to give to the many poor has been mocked from office.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.