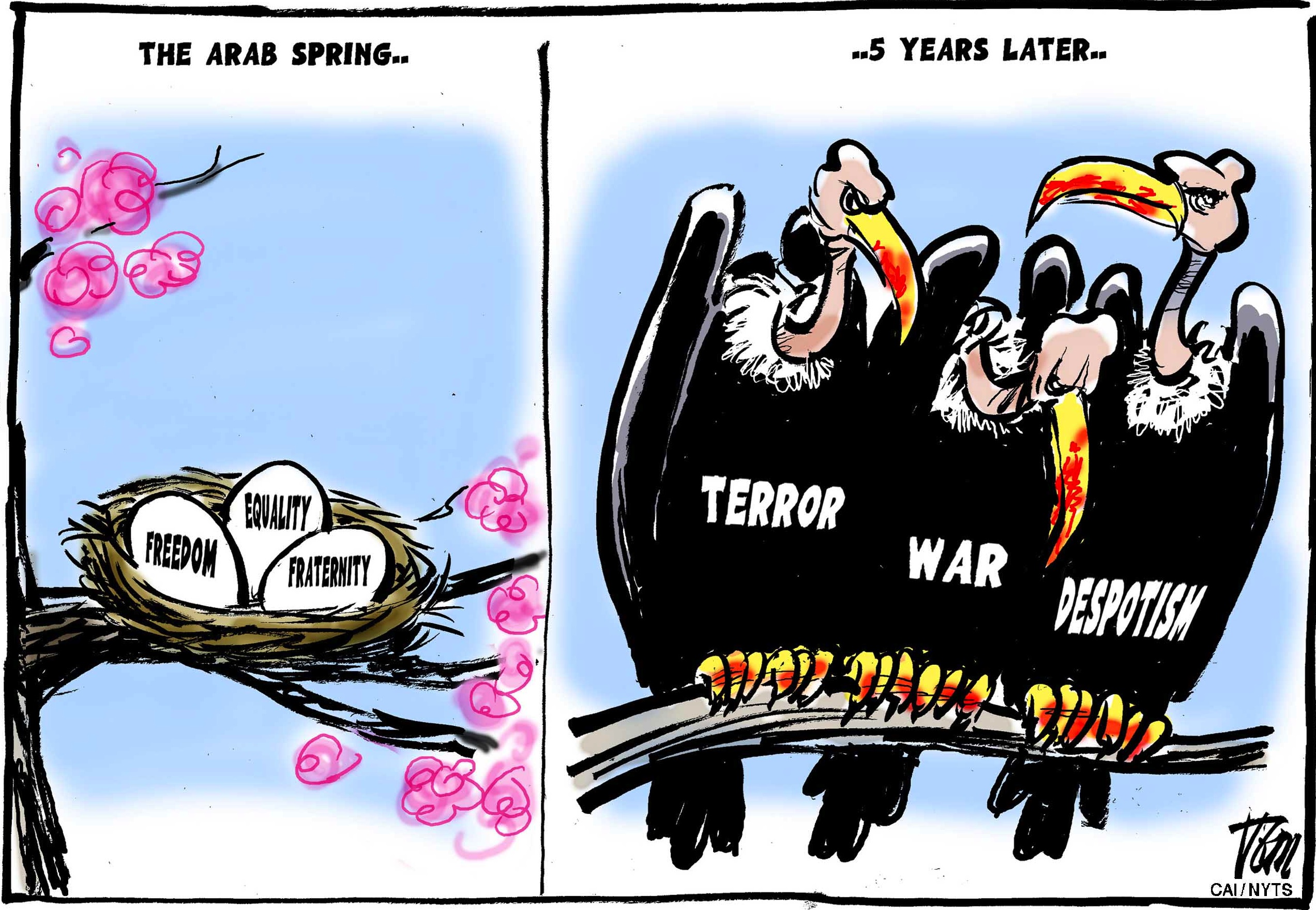

"Only the dead have seen the end of war." George Santayana's dictum seems particularly appropriate nowadays, with the Arab world, from Syria and Iraq to Yemen and Libya, a cauldron of violence; Afghanistan locked in combat with the Taliban; swaths of central Africa cursed by bloody competition — often along ethnic/religious lines — for mineral resources. Even Europe's tranquility is at risk — witness the separatist conflict in eastern Ukraine, which before the current cease-fire had claimed more than 6,000 lives.

What explains this resort to armed conflict to solve the world's problems? Not so long ago, the trend was toward peace, not war. In 1989, with the collapse of communism, Francis Fukuyama announced "the end of history," and two years later President George H. W. Bush celebrated a "new world order" of cooperation between the world's powers.

At the time, they were right. World War II, with a death toll of at least 55 million, had been the high point of mankind's collective savagery. But from 1950 to 1989 — the Korean War through the Vietnam War and on to the end of the Cold War — deaths from violent conflict averaged 180,000 a year. In the 1990s, the toll fell to 100,000 a year. And in the first decade of this century, it fell still more, to around 55,000 a year — the lowest rate in any decade in the previous 100 years and equivalent to just over 1,000 a year for the "average armed conflict."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.