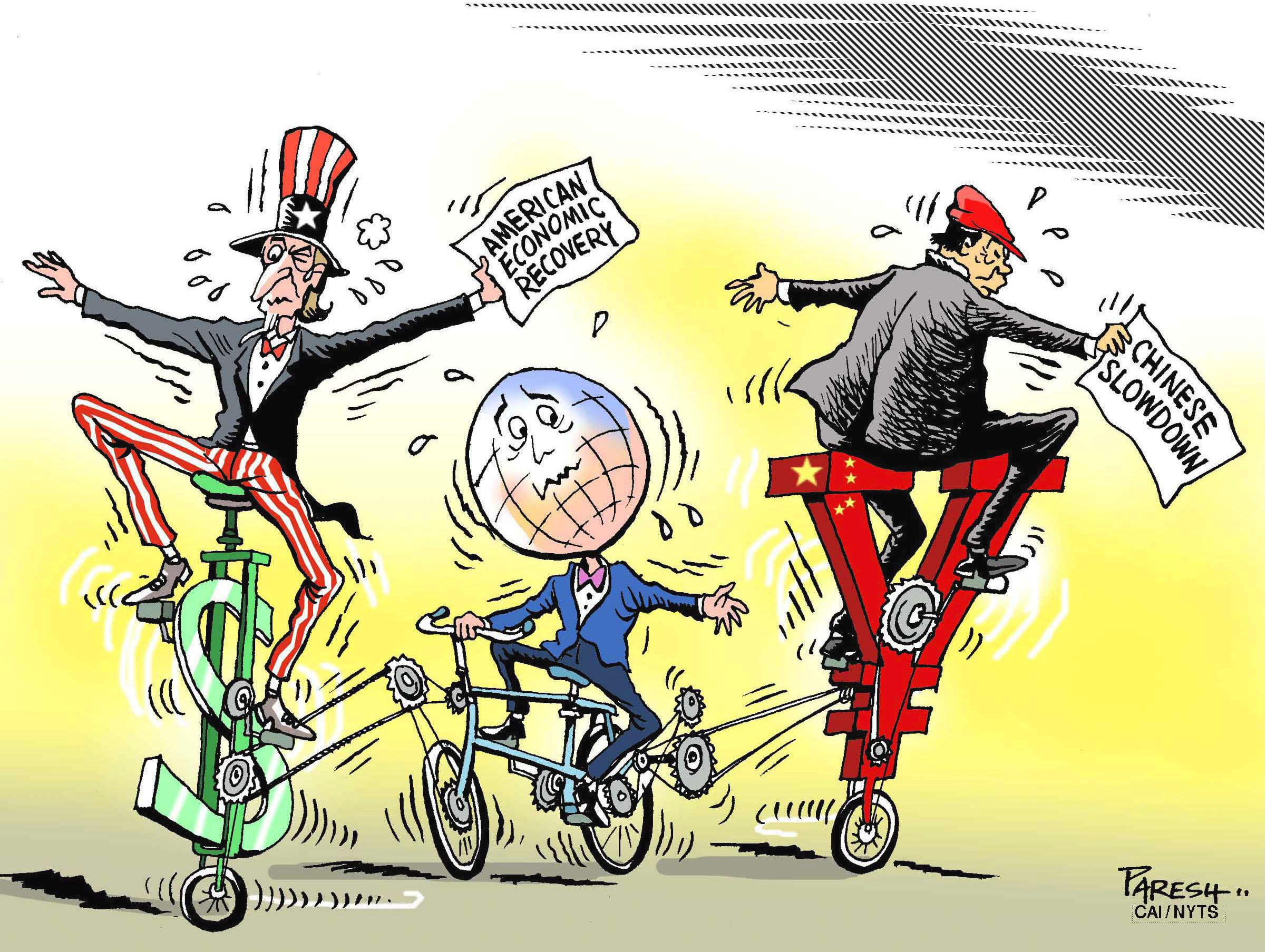

Earlier this month, global financial markets nearly imploded. From East Asia to Western Europe, currencies swooned and equity prices tumbled — all because of China's decision to allow a modest devaluation of its currency, the renminbi (RMB), also known as the yuan. China's economy is on the brink of collapse, pessimists warned. A new era of currency wars is about to be unleashed, doomsayers chimed in. To call this an overreaction would be a gross understatement.

Admittedly, the Chinese economy has been slowing, not least because of a sharp decline in the country's exports. And devaluation of the RMB could be viewed as an aggressive move to reverse the export slide and restore domestic growth — a move that could prompt competitors in Asia and elsewhere to push down their exchange rates as well, triggering an all-out currency war. So, in this regard, investor fears were not without merit.

But how serious was the threat? In reality, China's devaluation was puny — less than 5 percent in all. Compare that to the euro's 20 percent drop so far this year, or the yen's 35 percent dive since Japan embarked on its "Abenomics" reform program in late 2012, and it is clear that overblown headlines about the RMB's "plunge" were woefully misleading. Had China really wanted to grab a bigger share of world exports, it is hard to imagine that its policymakers would have settled for such a modest adjustment.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.