Yoshinori Suzuki quit his job as an administrator at a cram school to take over his family's farm in Niigata Prefecture. Now the 39-year-old rice grower is just trying to survive.</PARAGRAPH>

<PHOTO>

<TABLE WIDTH='300' ALIGN='RIGHT' BORDER='0'>

<TR>

<TD><IMG ALT='News photo' BORDER='0' SRC='../images/photos2009/nn20091204f2a.jpg' WIDTH='300' HEIGHT='189'/></TD>

</TR>

<TR>

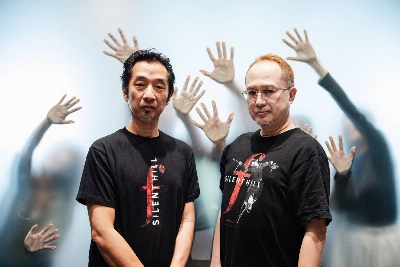

<TD><FONT SIZE='1'><B>Growth industry: Katsuichi Kobayashi stands in front of a paddy where he grows arrowhead potatoes in Iwatsuki Ward, Saitama.

</B> NATSUKO FUKUE PHOTO</FONT></TD>

</TR>

</TABLE>

</PHOTO>

<PARAGRAPH>'I never wanted to be a farmer,' he said. 'I've known since childhood that farming wasn't lucrative. I wanted to keep my administrative job.'</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>Suzuki came back because after his father passed away he felt compelled to help his aging relatives. Returning to farming is rare in his neighborhood, he said, because other farmers' children are engaged in more profitable, nonagricultural work.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>To support full-time farmers like Suzuki and revitalize the agricultural sector, the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Ministry under the Democratic Party of Japan is planning to funnel ¥561.8 billion into an income compensation system for farming households.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>Farmers would be paid the difference between higher production costs and market prices. The agriculture ministry hopes to get rice farmers nationwide into the program in April.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>The ministry, however, is in a tug of war with the Finance Ministry, which wants the subsidies to go only to large-scale farmers or farmers in targeted regions.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>The final shape of the program will remain unclear until the budget-making process for fiscal 2010 is finished later this month.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>The subsidy program for individual farming households 'will be too big as a model project,' said Yutaka Harada, chief economist of Daiwa Institute of Research. He argues that while the new system will stabilize the finances of full-time farmers, it should be applied first to those who grow wheat or soybeans — two crops now mainly imported.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>'It seems the DPJ is trying to show it is keeping the promise it made before the election to farmers,' he said, adding the farm ministry needs to cut some projects that are quite simply a waste of money.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>The economist said the ministry spent ¥50 million to open a farmers market in the Akasaka Sacas shopping complex in Minato Ward, Tokyo, but most of the money just went for rent.</PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>'They should invest money in the compensation system, not a project like that,' he said. </PARAGRAPH>

<PARAGRAPH>Nobuhiro Suzuki, an agriculture professor at the University of Tokyo –

, agrees that direct payments to full-time farmers would at least give them a minimum wage. "Their income is rapidly decreasing" because of declining food prices, he said.

The average annual income from farm products for full-time rice farmers was ¥3.37 million per household in 2007, according to the agriculture ministry, but "it is an income for a household with 2.6 people engaged in farm work," the Todai professor said.

Japanese farmers are sometimes criticized for being overly protected with subsidies, but he said in actuality they're not, compared with farmers in the European Union. "Ninety percent of their income is covered" because the EU budget is used to purchase the products when prices fall below the intervention price, he said.

In Japan, the prospect of an unstable income has been one of the main factors behind the dwindling numbers of full-time farmers.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.