Kanji Murakami began his reporting career in January 1941, joining the Asahi Shimbun's bureau in Seoul, or Keijo as it was then known, when the Korean Peninsula was under Japanese colonial rule.

At that time media censorship was strong. A 1909 law imposed many restrictions and curbed freedom of speech. Every newspaper was loyal to the Imperial government, which urged the nation to sacrifice for victory.

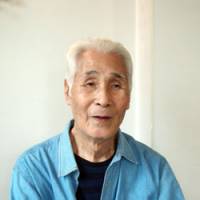

Murakami was assigned to cover day-to-day business at the Government-General of Korea, the Imperial government's headquarters for the peninsula. Now 92, Murakami recalled that reporters were allowed to ask questions to a certain extent at news conferences and reasonably free to walk around inside the government offices to do their reporting.

Murakami said in an interview with The Japan Times that he was troubled by the prevailing media censorship and the blatant discrimination the Korean people were forced to put up with at the hands of Imperial government officials.

One example, Murakami recalled, was when a bureaucrat overseeing public health said he was concerned about the rise in Japanese catching infectious diseases on the peninsula but rejected plans to improve sanitation because it would also mean saving the lives of Koreans.

"The official was a very nice person, but what he said represented the basic attitude of the Japanese (authorities) against Koreans at the time," the soft-spoken journalist said.

Murakami said he was personally against Korea being under colonial rule and claimed he did not harbor any discriminatory feelings toward Koreans. But he didn't write about the bigotry.

"Discrimination against Koreans was serious, but it was taken for granted, and we couldn't write those things. That's just the way things were," he said.

At the time, Koreans were forced to learn Japanese and to adopt Japanese names. Many had to endure harsh discrimination in every aspect of their lives as Japan tried to erase their culture.

Even so, Murakami said he forged close ties with Korean reporters who shared the same press club. It was through them that he was exposed to strong anti-Japanese sentiment. "One of them once told me that if Japan and the U.S. were to go to war, they would side with the Americans," he said.

Japanese reporters in Korea were aware of the hostility, but "newspapers, including mine, did not write these things for fear of the authorities and reported only the official line," Murakami wrote in his memoir "Yurakucho wa moeteita" ("Yurakucho was burning"), published in 1996.

"When we were growing up, Japanese society was already embracing militarism, and people probably didn't think of the war as an invasion. I vaguely thought it was, but then I didn't have the courage to openly run an antiwar campaign," he said.

Murakami, however, said he did his little part.

When asked to write about the public reaction in Korea on Dec. 8, 1941, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and drew the United States into the war, he reported that "it was eerily quiet."

While the words he chose were not explicit, the former Asahi reporter said he tried to convey the disquiet he felt that the Koreans calmly welcomed the news as the chance for their liberation. "I don't know how Japanese readers took it, though," he said.

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1915, Murakami was 20 years old when he quit Hosei University in Tokyo and went to live on the Korean Peninsula in 1935. Part of the reason was to help take care of a family matter there, but he admitted believing the move would also save him from being drafted. The Imperial Japanese Army units stationed in Korea were not being deployed to war zones.

But after war with China broke out in earnest in July 1937, Murakami was drafted into the army. As part of a field artillery unit, he experienced combat in Shianxi Province in northern China, but was demobilized in just over a year.

"(When drafted) I thought my life was over, so I felt really lucky," he said. "Of course I couldn't say this to anyone and just kept it to myself. But I doubt anybody was happy to be a soldier then."

Media censorship tightened as the war proceeded, and Murakami's work became even harder because he could not write freely.

In 1942, Murakami was transferred to Harbin in Manchuria, but was soon relocated to the newspaper's main bureau in Changchun, the capital of Manchukuo, to cover the Kwantung Army — the Imperial army unit that effectively ran the puppet state.

There, the army would only provide information at its convenience, and rarely, he said. Reporters also had limited access to army headquarters.

After learning from a passing soldier about Japan's defeat at the August 1942-February 1943 Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, Murakami felt the tide of the war was turning against Japan. The media, however, continued to minimize the "negative" and stressed a victorious Japan was still forging ahead.

Despite the state-positive propaganda and limited official information, Murakami said he was aware Japan was not winning. Gleaning bits of information from people from the front lines who passed through Manchuria, Murakami said he formed an objective view of the situation.

Murakami also knew Kwantung Army troops were moving south by train. The official explanation was that they were being sent to gather the remains of soldiers killed in fighting in Nomonhan near Mongolia in 1939. But in light of the information he possessed, Murakami sensed this was not true, and that they were in fact on their way to the southern front.

In early 1945, Murakami was recalled to Tokyo to take up a new assignment. On his way to Japan, he passed through Seoul and met with a high-ranking official he knew at the Government-General of Korea.

"He asked me, 'Mr. Murakami, how does the war situation look?' So without any words, I did this," the former reporter said, waving his hand slowly in front of his face in a gesture of futility. By then, Murakami knew it would not be long before Japan lost the war.

Mobilized again in May, Murakami was on a military base in Kagoshima Prefecture when the war ended on Aug. 15, 1945. Upon hearing of Japan's surrender, he thought of quitting as a reporter.

"I felt I should take responsibility for not writing the truth during the war," he said.

Colleagues who shared his concerns left the paper on Aug. 15, criticizing the Asahi for supporting the war and deceiving the public. Murakami said, however, the very same people sent him a letter urging him to stay on.

"I thought that was friendly advice from those who had regrets about leaving the paper abruptly out of rage," Murakami wrote in his book. Around the same time, he received a telegram from his boss urging him to return to Tokyo because changes were taking place within the paper that he should be a part of.

In the end, Murakami remained a reporter. "I was determined to cover the truth from then on" and report from the people's perspective, not the government's, he said.

Murakami's postwar work focused on labor issues. He spent his entire career as a rank-and-file reporter and retired from the Asahi in 1970.

Having witnessed the impact of Japan's militarism on the lives of many Koreans and Chinese during the war, Murakami is critical of today's political leaders for failing to establish good relations with neighboring countries even 62 years after the war's end.

"I think Japan has been leaning too close to the U.S. It's important to develop good relations with Asian countries," he said.

In this series, The Japan Times interview firsthand witnesses of Japan's march to war and ensuing defeat who wish to pass on their experiences to younger generations. This is the third installment of the Witness to War series. To read more, see the Witness to War archive.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.