To mark the 62nd anniversary of the end of the war, The Japan Times is publishing a series of interviews with firsthand witnesses of the country's march to war and crushing defeat. Each of our subjects — speaking with the authority that only those in the evening of life can command — testifies to the destruction humanity can inflict upon itself. But each has also shared their view of how younger generations can avoid the same tragic path.

If Masamichi Shida, 80, had known a bit more about the world back in 1942, he might never have become a kamikaze.

But Shida was just an impressionable junior high school kid when he took the first step toward being a warrior for the Emperor.

In 1942, the decision to enlist seemed proper. Basking in the glory of its successful surprise attack on Pearl Harbor the preceding Dec. 7, a seemingly invincible Japan had then overrun the Philippines and Malaya and crushed the British stronghold at Singapore.

"The war was ours to win," said Shida, now a tall, spry man with bushy mustache and beard.

It was with such optimism that the 15-year-old Shida passed the naval-academy exam that August.

Shida and many other people, though, were unaware that Japan had in June suffered a decisive reversal of fortunes, losing the Battle of Midway to the U.S. The Imperial navy lost four aircraft carriers, in excess of 300 planes and thousands of its best-trained warriors.

The military that Shida had just joined was already doomed, but Japan was none the wiser.

"There was nothing in the papers about the Japanese naval defeat," he said. "Would I have taken the exam if I knew we had been destroyed at Midway only two months earlier?"

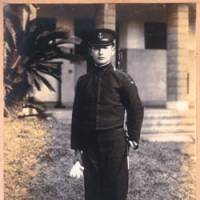

Shida set off for the naval academy in Hiroshima. He and other boys were arranged into squads of 50 and issued work clothes and "tanken" — the short sword that was the envied hallmark of a naval cadet.

Then the reality of military life sank in. Drills were conducted with brutal discipline and upperclassmen did not think twice about slugging new recruits for even the smallest transgressions. And learning to fly a fighter plane, as he found himself doing, didn't come easy.

But there was something much worse than the rigors of training. During his slightly more than two years at the academy, waves of senior classmates graduated, then died in droves at sea. Navy pilots, Shida said, perished in particularly large numbers. Japan had entered the throes of defeat.

When the military realized it could not prevent the Allies from retaking the Philippines, it began training pilots to dive straight into enemy vessels. Airplanes were strapped with bombs and extra gasoline tanks. Pilots were assured death, but — it was stressed — an honorable one in defense of the homeland.

The first attack by kamikaze, or "tokkotai" (special attack unit), occurred on Oct. 25, 1944, when five Navy pilots smashed their Zero fighters laden with 250-kg bombs into U.S. warships and transports off the Philippine coast. One of Shida's classmates was among the pilots.

Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi of the First Air Fleet judged the attack a success and called for additional suicide forces. More than 2,000 kamikaze aircraft were dispatched and are believed to have sunk 34 ships and damaged hundreds of others.

In March 1945, Shida himself graduated from the academy, and a week before being commissioned he and fellow pilots were handed a questionnaire asking: "Do you strongly desire to become a kamikaze? Or only moderately? Or not at all?"

Today, Shida takes great pains to explain what was going through his head when he chose certain annihilation. For starters, he'd worked hard up to that point and didn't want to back out now. And he was about to become an officer in a navy that placed honor before all else. He and most of his fellow pilots answered: "Strongly."

One comrade was rumored to have demurred and quietly left the unit in shame as the others looked on with a mixture of pity and contempt. The young man — this elite soldier — had disgraced himself. But before long, Shida would find himself envying his "courage" to resist the call.

A kamikaze was expected to fool the enemy into thinking he had no ill intent, then fall out of the sky to wreak havoc before antiaircraft fire found its mark. Shida's specialized training began.

By summer, his foreboding intensified. Waking after nights of practice flights in Hokkaido, he remembers hearing the cicadas' whine and thinking to himself, "They say an adult cicada dies after a week. How nice. At least they get to live out their lives, granted some kid doesn't get to them first. We kamikaze don't."

Training ended Aug. 12. The atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima, not far from the naval academy where his studies began, and on Nagasaki. But — as with Japan's debacle at Midway — news of the events barely reached him.

Around the 13th, he was told to prepare for redeployment to a base in Ibaraki Prefecture, from where he would fly his plane into a U.S. aircraft carrier. He thought his time was up.

"An order was an order. If they told you to die, you said, 'Yes sir!' " Shida said.

But fate spared Shida.

Partway on their journey to Ibaraki, on Aug. 15, the pilots' train pulled into the main station in Sendai.

The mood was surreal, and not only because Allied bombs had made a moonscape out of the city. The 36 tokkotai knew something was definitely off when the words "Commander Stalin" rang out. That most reviled of Soviet communists would never be honored with such a title. Unless, of course. . . .

The war had been lost. The pilots would not die in flames.

After weeks of idling at the Ibaraki base, where the men lived on foraged scraps and sake, Shida was finally dismissed. He returned to his home in Yokohama to find his entire neighborhood burned to the ground by U.S. bombs. By some stroke of luck, his was the only house that remained standing.

For some three decades after Japan's surrender, Shida flew for Japan Airlines — a job that offered new insight on the war.

One of several American fellow pilots at one point remarked, "In war, an order to undertake a mission with even a one-in-a-million chance of survival is not illegal. But ordering a kamikaze mission, that's murder." In Singapore, locals threw stones at him and Japanese flight attendants, probably to register their anger over Japan's oppressive 1942-1945 occupation.

Perhaps colored by such encounters, or maybe because he, too, came close to sacrificing himself in what he now describes as a reckless, imperialist adventure by his own government, Shida has become an outspoken critic of militarism — particularly Japan's security alliance with the U.S. and any attempt by political conservatives to tamper with the Constitution's war-renouncing Article 9.

Shida speaks tirelessly to public audiences and the press, and attends weekly vigils to oppose the U.S. war in Iraq. Yet, with six children and five grandchildren, Shida worries that younger generations cannot — indeed, seem unwilling to — grasp the lessons that he yearns to teach. "We Japanese forget war so easily," he said.

Article 9 states that Japan shall "forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes," that "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained" and rejects Japan's "right of belligerency."

And if there is one message he wants to get across, it is that the statute must remain. Otherwise, he believes, Japan's wartime past will come back to haunt it.

"Thanks to Article 9, Asians trust — well, not quite trust Japan — but at least view this country with some forbearance. But change Article 9 and Asians will believe we are a state capable of warfare and they will become tense," Shida said. "Then if Japan destroys Article 9 outright and sends soldiers abroad, Asia will explode."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.