Hannah Lewis couldn’t stop reading. She knew she was on to something.

An article in her local paper described how, facing a proposed road expansion in Nantes, France, environmental organization MiniBigForest created a small, dense planting of native tree species. These would quickly become forests that would protect residents from noise and pollution from the increased traffic while also offsetting carbon emissions. As she read, it became clear to Lewis, a researcher for the United States-based nonprofit Biodiversity for a Livable Climate, that this technique was the answer she’d been looking for.

It was called the Miyawaki method.

“I wanted to be able to do something about all these problems I was reading and writing about related to climate change — flooding, drought, intense heat waves, pollution — but it’s hard to know what to do,” says Lewis, who lived in France at the time. “The planting (in Nantes) recreated the ecosystem that had been there long ago, so it was ecologically sound and viable. It was also replicable. MiniBigForest went on to work with over a dozen different schools and community groups in the area.”

Lewis reached out to the organization and eventually proposed a similar idea in the French town of Roscoff. Planted in December 2021, this new mini-forest and the process of making it a reality became the seed for “Mini-Forest Revolution: Using the Miyawaki Method to Rapidly Rewild the World” (Chelsea Green, June 2022). Lewis’ book introduces similar reforestation projects in different countries and a how-to section for others and their communities to plant their own.

“People are aware that we have big problems but unclear about what they can personally do to make a difference,” Lewis says. “People all over the world ... saw this method as a good way forward.”

Created in the 1970s by Akira Miyawaki, a professor of plant ecology at Yokohama National University who passed away in 2021, the Miyawaki method calls for the creation of dense, random plantings of diverse, native trees and shrubs to combat deforestation. The mix, often anywhere from 10 to 30 different species, is tailored to the planting site’s particular climate and geology and creates a mature or climax stage forest destined to stand anywhere from hundreds to thousands of years. Saplings, selected at random from the species mix, are placed three per square meter and then heavily mulched with straw or other locally available natural material to suppress weeds and conserve soil moisture. After an initial three years of weeding and watering, a Miyawaki forest maintains itself with trees capable of shading out new weeds and growing an average of one meter a year.

The result after a few decades is a forest that would normally require nature hundreds of years to grow.

“The idea is based on ecological succession,” says Lewis. “In an earlier successional forest community, there are plants that need to grow in the sun. Climax species germinate in the shade of those other tall plants. When they finally take over the canopy, they shade out the earlier species such as pine, birch or poplar trees.

“That's what you're trying to recreate — that stable species composition of shade-tolerant plants that will perpetuate until the next ice age or some major disturbance.”

Dense stands of randomly positioned, diverse species are not only a hallmark of the Miyawaki method but also of mature, natural forests. The tight quarters of mixed types encourages plants to compete and collaborate as they create a mesh of life above and below ground.

“Different trees have different growth strategies,” says Kazue Fujiwara, professor emeritus of Yokohama National University and Miyawaki’s former research colleague. “For example, an evergreen oak grows to 20 or 25 meters, and it has a very deep tap root. The camelia, though, is an understory tree in a climax forest. It has a shallower root system that spreads and allows it to coexist with the big trees. These shallow and deep root systems make a network that stabilizes the soil and maintains water levels.”

The resulting water retention and soil stabilization make a Miyawaki forest ideal for slopes where landslides might be a concern due to deforestation or where monocultures dominate. Fujiwara works with The Association for Fostering a Green Globe to replant the slopes behind Tsukuba Shrine in Ibaraki Prefecture currently dominated by Japanese cedar and cypress plantations. A common sight on mountainsides everywhere in Japan, these species were planted post-World War II as a renewable cash crop for building materials. However, changing trade laws and modern construction materials made domestic timber too expensive, leaving more cedar and cypress trees than would naturally grow.

Today, many places in Japan feel the ecological impacts from this forest mismanagement.

“Cedar and cypress are shallow rooted trees,” Fujiwara says, “so a commercial forest is very weak in terms of strong wind or heavy rains. It is meant to be harvested after 45 years, which means nothing else grows underneath. When broad-leaved trees are added, the trees and soil hold water better. It will become a healthy forest.”

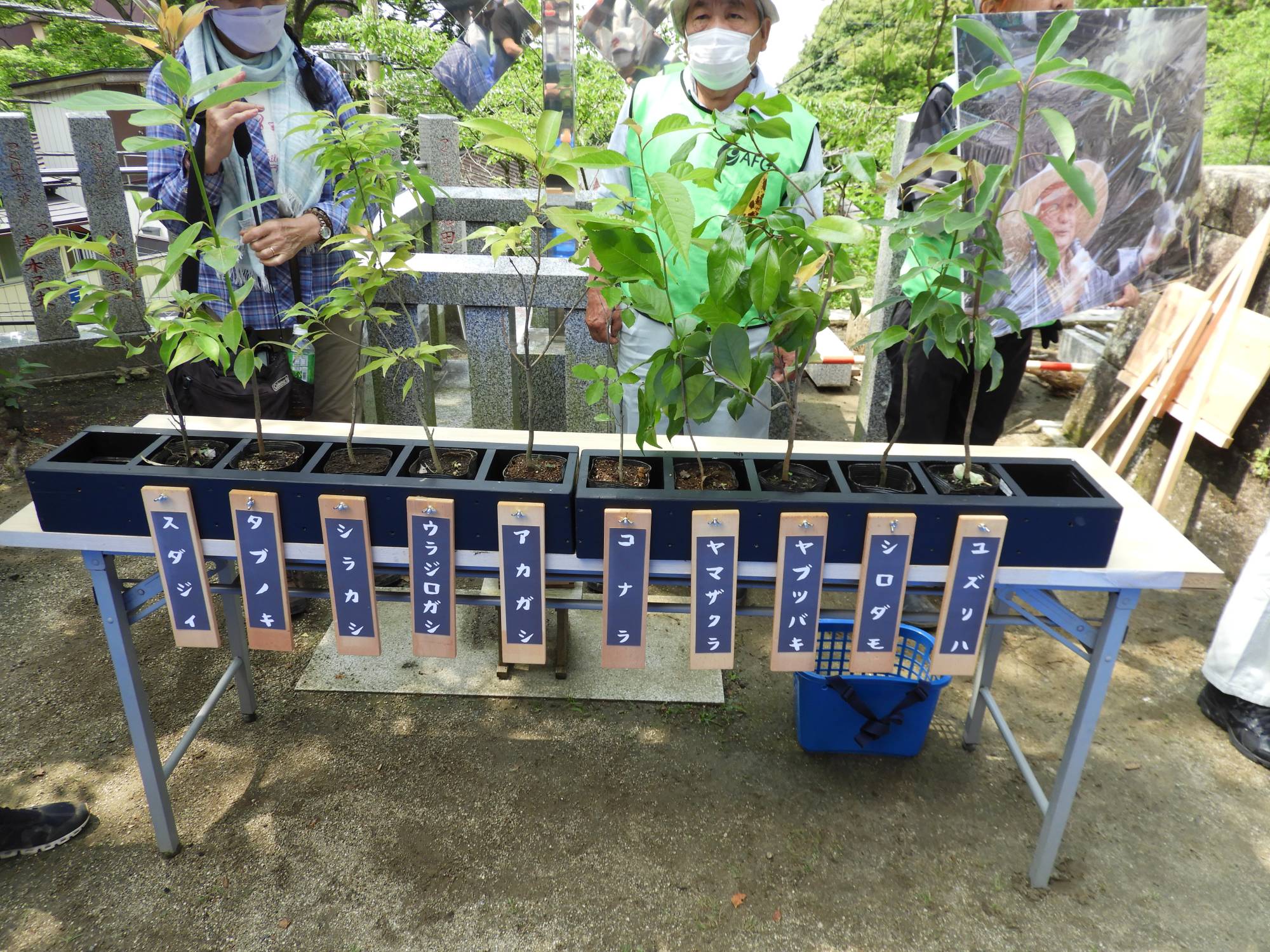

Since 2007, The Association for Fostering a Green Globe’s director, Ayako Ishimura, and its volunteers have raised saplings of native trees from seeds gathered around the Tsukuba Shrine area. Because the young trees are not planted until they reach a sturdy 3 years old, Ishimura estimates that each year they tend to upward of 50,000 seedlings in various stages of growth.

Once a location is selected and a planting date set, site preparation begins. In the case of Mount Tsukuba, plantation trees are thinned and their trunks used to create rough terraces along the slope. Branches are set aside for mulching the soil once the saplings are in the ground.

In June, 300 people gathered at Tsukuba Shrine to plant and mulch 1,000 seedlings on a roughly 500-square meter site. While the new saplings barely rise past the knees of volunteers, trees at a nearby spot planted four years earlier stand over eight meters tall between straight, red-barked columns of cedar and cypress. The soil underfoot is littered with leaves and tiny seedlings while birds and butterflies bustle overhead in the branches of shirakashi (bamboo-leaf oak), sudaji (chinquapin oak), yamazakura (mountain cherry) and yabutsubaki (Japanese camelia).

That dense weave of roots and trees is also what Makoto Nikkawa, organizer of Tohoku-based Mori No Project, was looking to bring up to Japan’s northeast. Spurred by the 2011 quake, Miyawaki enlisted Nikkawa and others to create a natural sea wall to check the power of tsunamis that regularly pummel this part of the coast. In addition to mitigating incoming waves, Miyawaki forests also stem the flow of debris back out to sea when the water retreats.

Begun in 2013, 10-meter-wide plantings in the towns of Iwanuma and Yamada, Iwate Prefecture, and Minami-Soma, Fukushima Prefecture, now flourish along the shore.

“If we plant and protect them,” says Nikkawa, “these natural forests will also protect us. They are part of our tradition and culture.”

That cultural legacy is what drew Kiyokazu Kusayama, chief priest of Izumo Taisha Sagamibushi in Hadano, Kanagawa Prefecture, to the Miyawaki method.

“After World War II, people associated the word for native forests, chinjunomori, with the armed forces and fighting because chinju also means military,” he says. “But native forests are the heart and soul of our culture. They are where diverse gods are enshrined, where the roots of Japanese culture and mentality are found. I wanted to change that perception, so I went to Dr. Miyawaki for help.”

In 2007, Kusayama and over 200 volunteers planted Hadano's first Miyawaki forest along the west side of his shrine as a 3,000 square meter buffer between it and a busy road and train crossing. Seventeen years later, more than 30 different species of trees rise as high as 20 meters on either side of a narrow path and waterway. Sunlight filters into the cool interior through leaves that rustle with birds and cool breezes while children on their way home from school search the stream for insects. Kusayama reports he has already seen fireflies this year.

Since then, he and the community have planted forests at schools, a hospital, along a major highway and at the site of a former garbage dump where a researcher plans to measure the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed over the course of five years. For Kusayama, each planting restores and deepens a connection between his community and nature that he believes will grow into the future.

“When people help with planting a forest, they become aware of the importance of trees and are more concerned about the environment,” he says. “It plants the green in their hearts.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.