When Yoshihide Suga declared in October that Japan would be carbon neutral by 2050, he became the first Japanese prime minister to set a specific timeline in the country’s bid to become emissions free.

As ambitious as Suga’s pledge may be, it’s far from being a pipe dream. The world is slowly taking concrete steps to address the climate crisis, and Japan simply can ill afford to sit on the sidelines any longer.

Japan is as vulnerable to climate change as any other country in the world. Its 2019 typhoon season was the costliest on record, closely followed by 2018. What’s more, scorching heat waves hospitalized thousands across the country in 2018 and 2019, while record rainfall in this period forced millions to evacuate from their homes.

“Typhoons that are supposed to (make landfall) only once in 100 years seem to be striking Japan every year,” says Soma Kondo, a spokesperson for Climate Youth Japan. “I think any more damage will have the entire country concerned about global warming.”

Many of these aspects of climate change are no longer projections, but realities. In 2018, the Environment Ministry reported that annual temperatures recorded in Japan are rising faster than the global average — and that the archipelago gets an extra day of “heat wave” weather once every five years. The report noted more days of heavy precipitation, fewer days of rain overall and a snow depth reduction of about 13% per decade.

It has recently become evident just how deep the consequences of climate change run in Japan, cutting deeply into the fabric of the country’s economy and society. The economic consequences of the climate crisis in Japan include storms that bring ruin to local infrastructure and businesses, and climate-related agricultural damage to pillars of regional economies and cultural pride such as rice, fresh produce and seafood.

The most dramatic consequence of the climate crisis comes in the form of increased rainfall and powerful typhoons. Annual instances of extreme precipitation in Japan have increased by 50% since the 1970s, and it has certainly felt that way: Between Typhoon Lan in 2017, Typhoon Jebi in 2018, Typhoon Hagibis in 2019, and torrential rain that caused millions to evacuate in western Japan in 2018 and Kyushu in 2017, 2019 and 2020, the impact has been nothing short of devastating. In 2019, damage caused by Typhoon Hagibis exceeded ¥1.8 trillion, a record for a water-caused natural disaster that wasn’t related to a tsunami. The previous record was the heavy rain recorded in Okayama and western Japan in 2018.

“Everything (is at risk),” says Miguel Esteban, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Waseda University. “From an engineering point of view, it would probably be better to move everybody out of this country and resettle them elsewhere.”

Tropical storms form as a consequence of heat and so, generally speaking, the hotter the weather, the more typhoons occur. Studies show that global warming has increased the proportion of severe tropical storms around the world.

Most of the economic damage during such storms occurs to infrastructure and buildings. Last summer, heavy rain in Kyushu killed 64, forced 200,000 residents to evacuate, caused 105 rivers to overflow, 316 mudslides, and, according to Kumamoto prefecture, monetary damage of more than ¥556 billion. The area around the Kuma River was particularly hard-hit, with houses and bridges being swept away.

“Heavy rain in Kumamoto in recent years has caused major floods and landslides,” says Toshio Fujimi, a professor of engineering at Kumamoto University’s Center for Water Cycle, Marine Environment and Disaster Management. “As a result, we have seen heavy damage to major roads and agriculture by sediment flowing into farmland, as well as the destruction of dams and reservoirs.”

There is also a ripple effect on local businesses and the local economy. In November 2019, Nikkei Asia reported that Typhoon Hagibis had significantly disrupted the tourist season in Hakone, cutting off mountain railway services as well as spring water to hotels and inns. Fujimi anticipates that Kumamoto will suffer from the same problem, as tourists shy away from visiting disaster-struck regions.

Even the temporary suspension of a bullet train can cast a long shadow over local economies in the nearby region.

“Tourist numbers have been slow to recover, even after the bullet train resumed operation,” Tateki Ataka, president of Hokkoku Bank in Ishikawa, told Nikkei Asia after Hagibis. “It seems that tourists remain reluctant to make trips as the impact of the typhoon lingers.”

And while rising sea levels in Japan don’t pose an immediate problem to many of the country’s residents, the World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that about ¥12 trillion will be needed to protect infrastructure and coastlines against a 1-meter rise in sea levels. And, as if that’s not enough, replacing infrastructure that is damaged by storms every year is difficult enough without having to set financial resources aside to fight COVID-19.

“The river flood defenses in Tokyo are currently being upgraded to withstand 1-in-200-year events,” Esteban says. “Adaptation is much cheaper than leaving things vulnerable.”

In a 2016 study, Esteban and his team calculated that the cost of inaction could exceed ¥100 trillion in damage, compared to the ¥370 billion investment required to upgrade Tokyo’s infrastructure to defend the city against storm surges and rising sea levels.

The climate crisis has also already led to changes for some of Japan’s most important agricultural products — first and foremost, rice.

When growing rice, high temperatures can cause white immature grain as well as cracked grain by reducing starch production and breaking apart the husk. The Environment Ministry reported that cases of both white immature grain and cracked grain have been increasingly seen around Japan — as well as a reduction in yield in unusually warm years. As early as 2012, 25 prefectures had already reported an increase in rice grain damage.

JA Oita, the regional cooperative of farms in Oita Prefecture, says that high temperatures and irregular, but extreme, rainfall have combined to make last year extremely poor in terms of a rice yield.

“The quality of the rice has deteriorated because the night temperature does not drop due to global warming,” says Yasunori Hitomi, a representative from JA Oita. “The number of ears of rice is also decreasing because of less rainfall overall. As a result, the rice-crop index of Oita Prefecture last year was 77, compared to the national average of 98.”

Extreme heat’s effects on rice quality and yields can have knock-on business consequences. When actual shipments don’t match the projected yields, the balance of supply and demand is disrupted, causing over- or under-supply and unexpected competition between different regions.

“We haven’t been able to make shipments according to our plan, so our prices won’t rise,” Hitomi says.

Projections suggest that 30% decreases in rice yields for most of Japan outside of Hokkaido and Tohoku are possible in the next 50 years.

Rising temperatures are also having consequences on fruit. The Environment Ministry has reported that high temperatures and low summer precipitation has caused damage to grapes, apples, persimmons, oranges and peaches.

A study on apples showed that negative effects of high temperatures have been observed in Nagano Prefecture, and predicted that the climate would be too warm to grow apples in the country by 2060. Farmers cited in the study were particularly concerned in the short-term over paler colored apples, which drastically lower prices, since the Japanese market highly values colorful fruit. Nagano farmers described earlier blooming as well as higher fall temperatures, later frosts and more hail storms — events all linked to the climate crisis.

Katsutoshi Osanai of JA Aomori says that high September and October temperatures are inhibiting the ripening of their apples and even burning the fruit.

“We haven’t seen large impacts on our vegetables yet, but the mild winter snowfalls ... (are) definitely a different climate from the old Aomori Prefecture,” Osanai says.

Storms can also bring devastation to farmers, such as when Typhoon Hagibis caused damage totalling ¥102 billion to crops such as rice, apples and cucumbers.

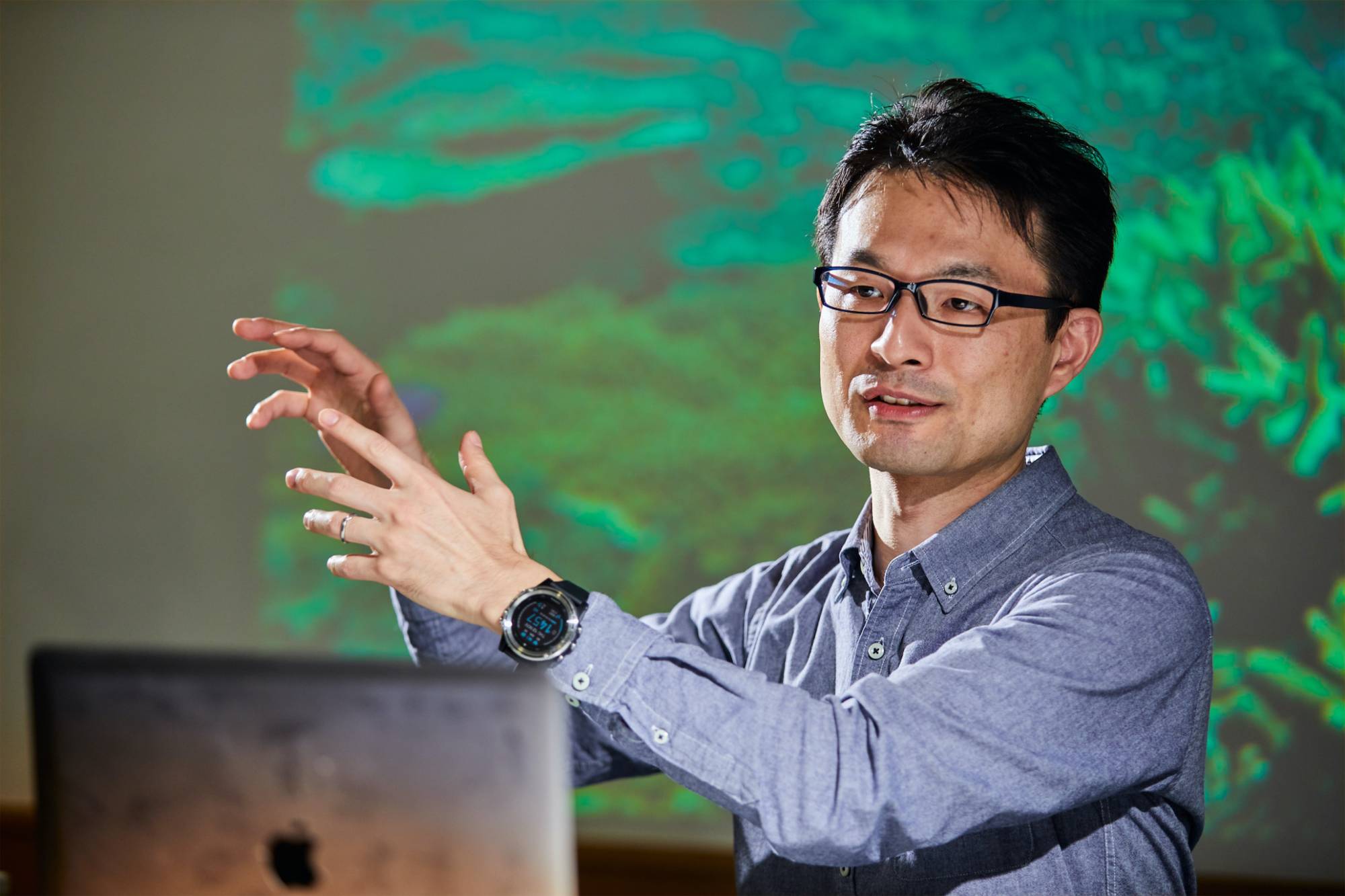

The climate crisis is further beginning to have effects on Japan’s fisheries. Jorge Molinos, a professor at the Arctic Research Center at Hokkaido University, who studies the effects of the climate crisis on the marine ecosystem, says that climate change is causing a rapid reorganization of marine life by relocating species within warming oceans.

Japan’s unique geography puts temperate waters in contact with tropical waters. Fish are sensitive to changes in temperature, so tropical species are pushing north.

“Tropical herbivorous fish, which are arriving in increasing numbers to the temperate costs of Shikoku or Kyushu are putting extra pressure on temperate seaweed, posing a serious threat to these valuable ecosystems,” Molinos says. “The tropicalization in Japan has many faces, like the expansion of tropical coral reefs ... or the population decline of temperate species.”

Challenges for the fishing industry have emerged all over the country, from Hokkaido’s salmon, Pacific saury and squid catches to the disappearance of abalone and anchovies in Tokyo Bay. While difficult to link directly to climate change, the salmon catch has plummeted in Hokkaido by 70% in the past 15 years.

“The fishing industry is very concerned,” says Shinichi Ito, a professor at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute at Tokyo University. “Higher water temperatures are causing problems for nori and wakame (seaweed).”

Large-scale losses of seaweed cultivation grounds were previously observed in Kyushu and Yamaguchi Prefecture in 2013. Then, in last year’s summer, local divers and fishers in Tokyo Bay reported the additional loss of seaweed beds. Tropical reefs were first confirmed in Kanto waters as recently as 2007.

“With the loss of the seaweed beds, large abalone, which were our local specialty, died out,” Koichi Hirashima, head of a local fisher’s association tells Kyodo News. Hirashima says that it has also become nearly impossible to catch anchovies and cherry bass in February due to higher ocean temperatures.

Adaptation to the climate crisis is possible and already underway. Farmers around Japan have even changed crops to get by. In the Nanyo region of Ehime Prefecture, farmers started growing Tarocco orange, which can tolerate higher levels of summer heat. On the islands and coastal areas of Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, farmers have begun cultivating avocados to cope with warmer climates. A sake brewery that operated in Nakatsugawa, Gifu, for nearly 150 years recently relocated to Hokkaido due to global warming.

“The colder the weather is, the better the quality of sake,” Koji Yamada, president and master brewer of the company tells the Asahi Shimbun. “This is an issue we must resolve over the next 100 years.”

Hokkaido fishing operators, already suffering from poor salmon hauls and encountering inedible sunfish for the first time ever, are rapidly changing to yellowtail and even bluefin tuna in order to stay afloat.

“Yellowtail is an important fishery item mainly in southern Japan,” says Naoki Kumagai, a researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Studies. “When it started to be caught in Hokkaido, it was (worthless). Now however, yellowtail has been priced well also in Hokkaido.”

But the cultural loss cannot be quantified. The indigenous Ainu people had 133 words for salmon, the crucial ingredient in Hokkaido’s beloved sashimi rice bowl. Fishing operators can catch yellowtail instead, but what is Hokkaido without salmon?

To protect their apple trees, farmers in Nagano Prefecture delay harvests and place reflective materials on the ground. But even these measures can’t prevent severe typhoons from wiping away entire harvests, much like Hagibis did two years ago. Nagano Prefecture is highly prized for its apples, and currently contributes to 18% of the national harvest. What is Nagano Prefecture without apples?

Thus, the climate crisis has begun to threaten long-standing regional specialties and local culture. The prices and accessibility of fish, fruit, grain and vegetables may create consequential changes in the economic and cultural life and image of regions around Japan.

Climate change, with its challenges, brings opportunities for innovation. The Environment Ministry reported on the growth of agriculture support services and technologies to improve the heat tolerance of buildings.

“The past few years have seen Japan’s national resilience — green infrastructure, smart city and other initiatives — turned into platforms that specifically link national agencies, subnational governments, business and civil society,” says Andrew DeWit, a professor of economics at Rikkyo University. “These partnerships have seen growth rates of several hundred percent over the past year.”

The larger problem is that Japan’s climate policy, despite Suga’s ambitious declaration, remains in limbo. After the 1992 Kyoto Protocol, Japan’s climate strategy was based on nuclear energy. However, following the nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima No. 1 power plant in 2011, Japan deactivated all of its nuclear reactors — and just a handful remain in operation today. This shift led to a decade of resurgent fossil fuel use in the 2010s. Combined with stagnation in renewable growth, Japan is far from reducing emissions targets that align with the Paris agreement’s objectives.

“Since the Environment Ministry is in charge of climate change policy, measures are limited to homes and offices, and there is no energy or transportation policy,” says Kenrou Taura, a representative from Kiko Network, a Kyoto-based climate organization. “Many of the policies have further convinced people that measures against climate change are inconvenient and inhibit economic growth.”

Now, climate change itself is inhibiting economic growth, affecting infrastructure, rice, fruit, fisheries — and livelihoods — across Japan.

“We do not disregard individual efforts to be eco-friendly, but we believe there is a need for major social and economic changes,” Taura says. “We need adaptation and mitigation measures for each region, and information and educational programs to promote the participation and understanding of residents. Raising CO2 reduction targets should be given top priority.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.