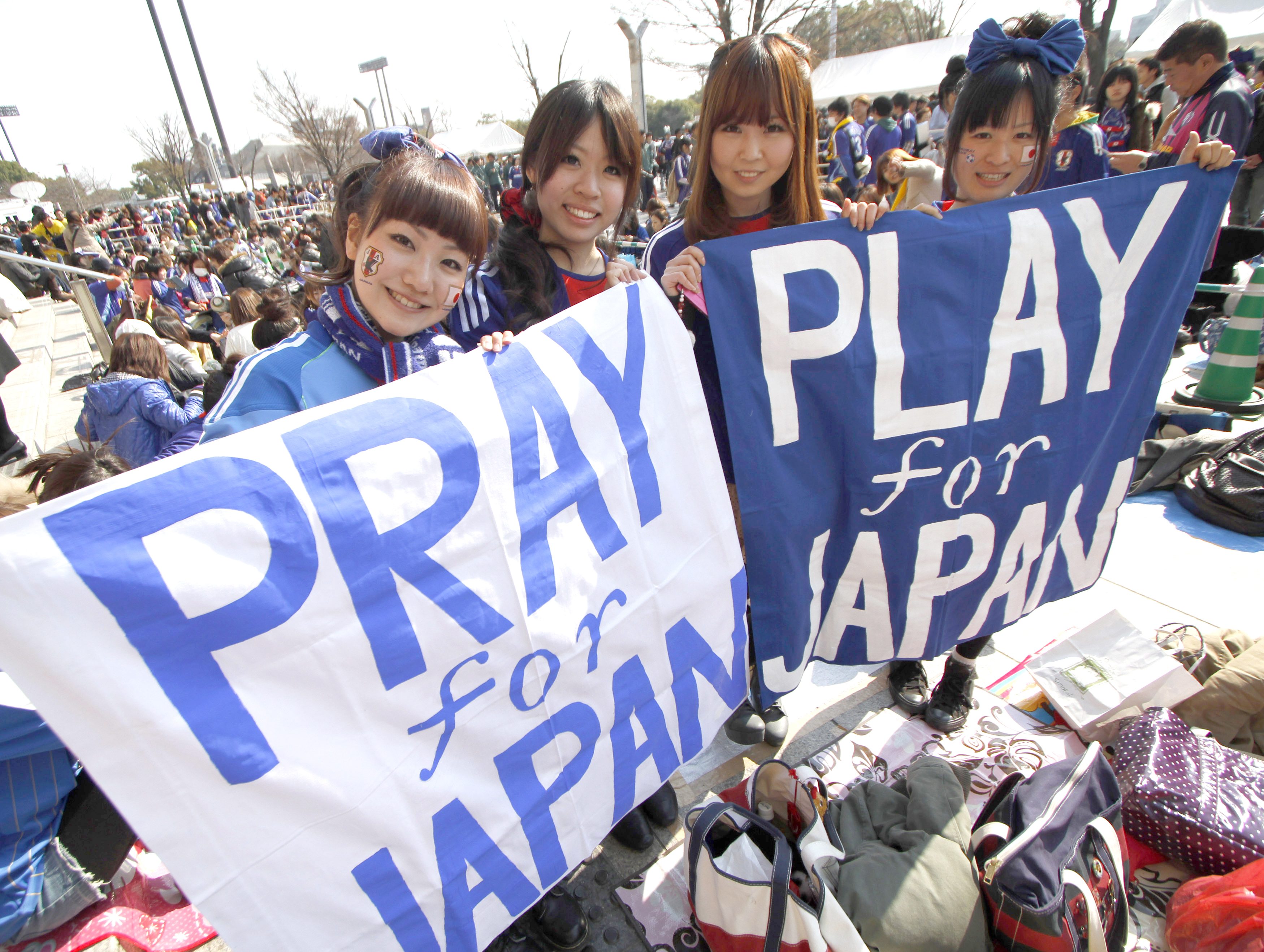

My friend Naoki has a new strategy when it comes to getting dates; these days he says the best bet is to kusuguru (くすぐる, tickle, or appeal to) a woman's sense of aikokushin (愛国心, patriotism).

This seems like a risky undertaking, considering that aikoku (愛国, love for one's country) used to be a dirty word. Back in the 20th century, the combination of the kanji characters ai (愛, love) and koku (国, country) immediately alerted one to the presence of uyoku (右翼, right wingers), which meant the yakuza (ヤクザ, gangsters) couldn't be far behind. Normal, law-abiding young women professed zero interest in anything remotely wa (和, specifically Japanese) and poured their energies into procuring Italian handbags.

Before minshu shugi (民主主義, democracy) set in, chūkun aikoku (忠君愛国, loyalty to the emperor and love for Japan) was hammered into each and every kokumin (国民, Japanese citizen). Among other things, it encouraged zettai fukujū (絶対服従, absolute obedience) to power and authority. After World War II, the Allied Occupation put a rapid stop to that, and aikoku was replaced by kojin-shugi (個人主義, individualism) which implied among other things, that it was best to keep one's national identity under wraps. Admitting to one's Japaneseness came with a pretty heavy burden, having to do with buryoku (武力, armed force), haisen (敗戦, defeat) and kutsujoku (屈辱, humiliation).

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.