Somewhere in the South Pacific, thousands of miles from the nearest landfall, there is a fishing ship. Let's say you're on it. Go onto the open deck, scream, jump around naked, fire a machine gun into the air — who will ever know? You are about as far from anyone as it is possible to be.

But you know what you should do? You should look up and wave.

Because 438 miles (705 km) above you, moving at 17,000 miles per hour (27,360 km per hour), a polar-orbiting satellite is taking your photograph. A man named John Amos is looking at you. He knows the name and size of your ship, how fast you're moving and, perhaps, if you're dangling a line in the water, what type of fish you're catching.

Sheesh, you're thinking, Amos must be some sort of highly placed international official in maritime law. ... Nah.

He's a 50-year-old geologist who heads a tiny nonprofit called SkyTruth in tiny Shepherdstown, West Virginia, year-round population, 805.

Amos is looking at these ships to monitor illegal fishing in Chilean waters. He's doing it from a quiet, shaded street, populated mostly with old houses, where the main noises are (a) birds and (b) the occasional passing car. His office, in a one-story building, shares a toilet with a knitting shop.

With a couple of clicks on the keyboard, Amos switches his view from the South Pacific to Tioga County, Pennsylvania, where SkyTruth is cataloging, with a God's-eye view, the number and size of fracking operations. Then it's over to Appalachia for a 40-year history of what mountaintop-removal mining has wrought, all through aerial and satellite imagery, 59 counties covering four states.

"You can track anything in the world from anywhere in the world," Amos is saying, a smile coming into his voice. "That's the real revolution."

Amos is, by many accounts, reshaping the post-modern environmental movement. He is among the first, if not the only, scientist to take the staggering array of satellite data that have accumulated over 40 years, turn it into maps with overlays of radar or aerial flyovers, then fan it out to environmental agencies, conservation nonprofit groups and grassroots activists. This arms the little guys with the best data they've ever had to challenge oil, gas, mining and fishing corporations over how they're changing the planet.

His satellite analysis of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010, posted on SkyTruth's website, almost single-handedly forced BP and the U.S. government to acknowledge that the spill was far worse than either was saying.

He was the first to document how many Appalachian mountains have been decapitated in mining operations (about 500) because no state or government organization had ever bothered to find out, and no one else had, either. His work was used in the Environmental Protection Agency's rare decision to block a major new mine in West Virginia, a decision still working its way through the courts.

"John's work is absolutely cutting-edge," says Kert Davies, research director of Greenpeace. "No one else in the nonprofit world is watching the horizon, looking for how to use satellite imagery and innovative new technology."

"I can't think of anyone else who's doing what John is," says Peter Aengst, regional director for the Wilderness Society's Northern Rockies office.

Amos' complex maps "visualize what can't be seen with the human eye — the big-picture, long-term impact of environment damage," says Linda Baker, executive director of the Upper Green River Alliance, an activist group in Wyoming that has used his work to illustrate the growth of oil drilling.

This distribution of satellite imagery is part of a vast, unparalleled democratization of humanity's view of the world, an event not unlike cartography in the age of Magellan, the unknowable globe suddenly brought small.

With Google Earth, any bozo can zoom in from a view of the globe to their house, the car in the driveway. Google and Time magazine recently developed Timelapse, a website that lets viewers pick a location and see a time-lapse video of how it has developed over 30 years. Last year a German enthusiast put together a stunning time-lapse video of the world at night, with images taken from the international space station.

"It's revolutionized the whole way we analyze things; it's transformed the way the Earth is pictured," says James B. Campbell, author of the collegiate textbook "Introduction to Remote Sensing" and professor of geography at Virginia Tech, speaking of satellite imagery in general and Amos' work in particular. "You can see the growth of cities, the growth of irrigation systems, agricultural patterns, the way we use water resources and transportation systems, the tremendous growth in the amount of land we've paved over and devoted to roads and parking lots and airport runways."

The world, and what we've done to it. Do we really want to look?

Let's go back to that fishing ship in the Pacific: How does Amos know so much about fishing ships, anyway?

First, the basics: Chilean officials wanted to know if they had an illegal fishing problem off Easter Island, their territory 2,000 miles (3,220 km) off their coast. Chile was working with the Pew Charitable Trusts on the issue; the trusts hired SkyTruth to figure it out.

The problem: These waters are one of the most remote places on Earth and cover 270,000 square miles (700,000 square km).

Amos began by going small: What would fishermen be after? Tuna and swordfish, it turned out. They were fished in certain seasons, and that narrowed both the type of ships he was looking for and when.

Next, Amos started buying Automatic Identification System data. AIS is sort of like air-traffic control on the high seas: Ships send radio signals with the ship's name, size, speed and ownership, little identifying radar blips. But this didn't quite solve the problem: Fishing vessels are exempt from having to use AIS transponders, since captains don't want competitors to know where they're fishing.

Still, Amos used AIS as a screen to identify most ships passing through Easter Island's no-fishing area, and this formed his first layer of data.

Next, he hired a multinational satellite operation (Canadian-built, Norwegian-operated) to take radar images. Although each image covered an area of 115 miles (185 km) by 115 miles (185 km), the region was so vast that Amos needed strips of images to create a composite. This meant the satellite had to take a sequence of photographs. It took nine sequenced images: three strips of three images, taken from three orbits of Earth, at about $5,000 per image.

Now he had a map of ships in the area on a specific day and time, and this formed his second level of data.

He then matched the days and times of both maps — the AIS information and the radar images — and laid one over the other. Here's a freighter loaded with cars, steaming from South Africa to Japan, check. There's an international cruise ship, check.

But the radar map also showed other ships, ones with no transponders. Since they were in protected waters during fishing season, they were highly suspicious, some making the telltale back-and-forth patterns of trawling nets.

"If the ship is big enough for us to detect on a satellite image, and they're not broadcasting, we're pretty sure it's a fishing vessel," he says, acknowledging it could be even more serious illegal activity, such as human trafficking or drug running.

There — unidentified ships in the South Pacific, running without transponders — spotted from 5,000 miles away by a couple of guys looking at computer screens in a tiny office just a couple of blocks from the Blue Moon Cafe over on High Street.

In late October 1946, U.S. Army scientists in New Mexico developed film from a V-2 rocket, pictures taken of the American Southwest from 65 miles (105 km) up. It was grainy and black-and-white and, basically, you couldn't see a darned thing.

This is officially the first picture of Earth from "space," and the dawn of the new era. Amos' dad, Fred, was at the White Sands Missile Range at the time, in the Army's 1st Guided Missile Battalion, a crew that tracked and filmed those rockets. It's likely he saw that very launch.

The picture that changed everything, though, was "Earthrise," or NASA image AS8-14-2383, one of the most widely viewed pictures in history. As Apollo 8 circled the moon on Dec. 24, 1968, Earth rose on the horizon.

"Oh, my God, look at that picture over there," exclaimed mission commander Frank Borman. With a handheld camera, astronaut William Anders snapped a picture of Earth — a startlingly blue, startlingly delicate half-sphere — floating in a black void, above the pockmarked surface of the moon.

Galen Rowell, the famed nature photographer, dubbed it "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken," for it showed just how lost and alone we were in the cosmos.

John Amos, growing up in Rochester, New York, remembers that photograph, for he grew up in a scientific household.

His father, after completing his military service, became a geologist and paleontologist for Ward's Natural Science Establishment, a firm supplying instructional materials to science teachers. His mother, Jackie, worked at the public library and, at night, ironed her children's socks and underwear.

In this highly disciplined environment, the fields of science, astronomy, geology gleamed. The natural world seemed a wonder box teeming with mysteries.

"I can recall many frigid, crystal-clear winter Rochester nights in the back yard with Dad, gazing at the rings of Saturn and looking for meteorites while trying to ward off frostbite," Amos wrote in a eulogy for his father earlier this year.

Landsat, the first Earth-gazing satellite (a joint project of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey), went up in 1972, when Amos was 9. It orbited the poles, 560 miles (900 km) up, with two cameras.

Today — well, what hicks we were then! Gushing about Earth because it was blue! Taking pictures with film! Today, we are on Landsat 8 — 438 miles (705 km) up, orbiting every 99 minutes — and it is only one of dozens of civilian satellites gazing down at us. To put the speed of change in perspective, consider this:

A few weeks ago, 45 years after "Earthrise" dazzled Amos and the rest of the world, NASA engineers in Greenbelt, Maryland, finished building a microwave radiometer that will go on a satellite next year. It will map soil moisture levels, taking 192 million samples per second, via a microwave beam that simultaneously filters out other microwave emissions, goes through vegetation, and gathers the "naturally emitted microwave signal that indicates the presence of moisture," according to NASA. Armed with information about the dirt beneath our feet, those microwave beams will then ricochet to the satellite, then down to laboratories for analysis.

This was scarcely reported upon.

On the morning of April 21, 2010, Amos flicked on his home computer and saw that a BP oil rig had exploded overnight.

He blogged about it, warning that the damage might be severe. Within a day, he was looking at satellite images: "SkyTruth analysis of two NASA satellite images taken hours apart yesterday suggests the Deepwater Horizon rig may have been drifting."

This was an editorial "we," as Amos was SkyTruth's only employee, but this would be his defining moment, and he was well prepared.

After leaving home, he had gone to Cornell University, then to the University of Wyoming for a graduate degree in geology. He married his college flame, another outdoorsy New Yorker, Amy Mathews, and the couple settled in an Arlington, Virginia, bungalow.

Amos was no environmental radical. He went to work for consulting firms that used satellite technology and remote sensing to search for oil and gas. It's highly technical work. Ask him how to detect oil deposits in satellite pictures of rock formations, and he'll pause and say: "pattern recognition."

His wife, a committed environmentalist for nonprofit groups, politely considered her husband to be working for the enemy.

"I didn't say anything," she says now with a laugh. "John's job paid, and we were a young couple that needed the paycheck. I didn't want to dictate to him what was acceptable, but I could see it wasn't satisfying to him."

As the years passed, Amos was, in fact, developing second thoughts. He says a "series of small epiphanies" led to his conviction, in the late 1990s, that he was aiding in the overconsumption of Earth's resources. Given his family background, this was a serious moral issue.

The decisive moment came when he came across a 1993 image of the Jonah oil field in Wyoming: sagebrush, grassland, cows, pronghorn antelope, a few gravel roads. He got a fresh image for a project he was working on. In just a few years, the gas wells — five-acre (2-hectare) pads — had multiplied, as had the roads accessing the remote sites.

"It had gone from ranchland to industry, just that fast," he says.

Deeply concerned that he had been using his talents in a "disservice to the planet," he started SkyTruth in 2001. He had no clients, no resources and no fundraising experience. He worked on a throwaway desk in the couple's unfinished basement with a space heater for warmth. He got one grant for $15,000 his first year, as seed money, and $16,000 his second year. The couple had decided not to have children, so the only risks they were facing were their own, but still: This was not a promising start.

Mathews was doing consulting work from a home office on the second floor, and the couple did not fraternize during work hours. "We sent each other emails," she says now. "It was a little weird."

At the same time, they were burning out on Washington — "the glamour was sort of gone," Mathews says. They attended Shepherdstown's annual arts festival one year by chance. They fell in love with its Mayberry charm and in 2003 bought a house outside town, the back deck hidden in a canopy of shade trees.

Amos worked in a 3-meter by 3-meter office just off the kitchen. He worked on projects in Wyoming and Appalachia, and documented oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico after Hurricane Katrina. He was sometimes asked to testify before congressional committees about oil and gas exploration, but there was very little funding.

"John's bigger problem was not if he could single himself out as unique," says Angel Braestrup, executive director of the Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, who gave SkyTruth its first grant. "It was, could you take the awareness that the organizations on the ground needed a higher [scientific] power, and connect that story to donors, who were unaware of the need."

Of course, a lot of people didn't like his work, perhaps none more so than Sen. Mary Landrieu, Democrat of Louisiana, a staunch supporter of offshore drilling.

When Amos finished testifying about the danger of such drilling before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in November 2009, Landrieu mocked him repeatedly. At one point, she asked him to read a chart saying offshore drilling accounted for 1 percent of oil spills. When he said he was too far away to see it clearly, she said, voice dripping sarcasm, "Well. Let me try to read it for you."

After a few more gibes, she turned to lecturing. Offshore drilling, particularly conducted by rigorous American standards, she said, posed no realistic threat to the environment. She said he was trying to frighten people with misleading satellite photographs.

"You do a great disservice — you and your organization — in not telling the American people the truth about what happens in domestic drilling, on shore and off, and putting it in the perspective that it deserves," she said.

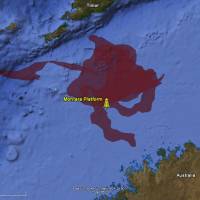

Five months later, in April 2010, Amos was looking at the BP oil spill, 41 miles (66 km) off the coast of Landrieu's state. It was doing something Landrieu had said couldn't happen to an American-run well: spew out of control. The oil slick spread to 817 square miles (2,116 square km), then to 2,223 square miles (5,757 square km), he could see from NASA satellite images.

Given that range, Amos reasoned, the BP and the Coast Guard official estimates of 1,000 barrels per day couldn't be right.

Oil is lighter than water, so most of it floats to the surface and spreads out in layers just microns thick. But to reflect enough light to be seen from above, it has to be a certain thickness, giving rise to established formulas about the size of spills.

Amos and Ian MacDonald, a friend and an oceanographer at Florida State University, figured that the spill had to be at least 5,000 barrels per day, and perhaps many times higher, depending on the size of underwater plumes.

On April 27, Amos blogged: "Based on SkyTruth's latest satellite observations today of the size of the oil slick and published data on the thickness of floating oil at sea that produces a visible sheen (1 micron, or 0.000001 meters) we think the official estimate of the spill rate from the damaged well has been significantly too low."

He went on to catalogue his computations with MacDonald, concluding that the spill had to be at least 6 million gallons — about half the size of the Exxon Valdez spill, then the worst in American history — and was now gushing at 20 times the rate that BP and the Coast Guard reported.

By May 1, the pair was saying the spill had passed 11 million gallons.

Their report was picked up by environmental groups and news organizations. The federal government immediately upped its estimate to 5,000 barrels per day. The blog went viral. Amos became a hot television news property. He was quoted in The Washington Post, The New York Times and dozens of others.

Spill Cam, the unofficial name for the company's video of oil gushing out of the underwater ruptured pipe, transfixed the nation. The government's new spill-rate estimate was quickly questioned by the news media, dismissed as too low, with MacDonald and Amos being quoted as the more reliable experts. The Coast Guard gave up, saying exact estimates were "probably impossible." A BP official said, in May, "there's just no way to measure it."

But MacDonald and Amos were pretty accurately estimating the spill, co-writing a New York Times op-ed piece late in the month that argued that such estimates were vital to cleanup and restoration.

Landrieu, talking to National Public Radio's Scott Simon, in June, eight months after she had ridiculed Amos, sounded much different.

"BP made some terrible judgments about how this should — well, should have been operated, closed, you know, brought online — terrible judgments." Her website credits her with playing a leading role in legislation that directed "80 percent of the Clean Water Act penalties paid by BP directly to the Gulf Coast."

When her public affairs staff members were asked recently if the senator had changed her mind about SkyTruth, they responded with a statement from Landrieu saying that she thought BP should pay for the spill. It did not address SkyTruth. When asked again about SkyTruth, they did not respond.

The size of the spill is still being fought out in court. But it's at least 172 million gallons (651 billion liters).

SkyTruth had broken through.

On a recent morning in Shepherdstown, Paul Woods, SkyTruth's new chief technology officer, is working with two interns on maps that will detail fracking operations in Tioga County, Pennsylvania. He's also on a Skype call with Egil Moeller, a computer programmer in Göteborg, Sweden, whom they've hired to build a crowdsourcing website. The idea is to give volunteers a short online tutorial, then have them make simple classifications (active, not-active, etc.) about each drill site, based on aerial and satellite imagery.

This will help build county and statewide maps of the reported 3,600 Pennsylvania fracking operations. Woods says there are "gaps in the state data" that make it unclear if some permits were ever drilled, or if some drill sites actually used the high-pressure water blasting techniques that have made fracking so controversial.

There are other truth-squadding projects such as tracking natural gas flares in Nigeria and a crowdsourcing project about water quality in Appalachia, and the list keeps getting longer.

SkyTruth is no longer a one-man show, and it's no longer quite so tiny. Annual donations and grants had averaged about $75,000 per year before the gulf oil spill, but are now at $405,000. There are four full-time employees, two paid interns. They're active on their blog, on Facebook and Twitter, and Amos now spends more of his time fundraising and less on the technicalities.

"We want to play Tom Sawyer, to get the whitewash and the fence, and then get people to do the rest of the work, looking at their own patch of the planet," Amos is saying. "Really, what I'd like, the goal here, is for 'SkyTruthing,' to be an activity, a verb, like 'Googling.' As in 'I Googled this' or 'I SkyTruthed that.' "

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.