In 1983, I talked myself into a marvelous job with a Japanese magazine. I set off in the early summer, when the days would be long and the nights short, to tour around Scotland with cameraman Moriyama Touru. We visited as many whisky distilleries as we could, with Touru doing the driving and, during the day at least, me doing the story-gathering and whisky-tasting.

The previous year I'd spent a month in India and Nepal filming a whisky commercial. That was fun too. It also got me an invitation to visit the Nikka whisky distillery in Yoichi, Hokkaido, which, despite it being in Japan and not Scotland, is one of the most traditional distilleries in the world of the nectar known in Gaelic as usquebaugh (meaning "water of life") — which in its short form, usky, is the origin of the word "whisky" in English.

I was met by car at Chitose Airport and driven through Sapporo to Yoichi. It was a long journey, and having come all the way from Kurohime that day, I dozed off in the back seat and only awoke as we drove through the big stone gateway of the distillery. It had been snowing.

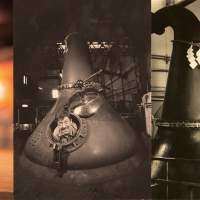

Stepping out of the car, and looking around at the stone buildings, the smoke coming from a tall chimney, billows of steam carrying the fragrance of whisky all around, I felt as if I had been magically transported to Scotland. The stones even had the distinctive black staining caused by an airborne, alcohol-loving fungus.

My very gracious hosts escorted me to a visitors room that was just like a lounge in a castle somewhere, with big old furniture and a toasty warmth from its log fire. There they handed me a glass of one of the best single-malt whiskies I'd ever had.

In those days, everyone believed that the better Japanese whiskies were that way because Scottish malt whisky had been blended into them — which was, to some extent, quite true. Nobody was putting pure Japanese malt whisky out onto the market, they were just using it in their many blends.

Yet as that liquid amber passed my lips and slid delightfully down my throat, so smooth, so warming, with just the right touch of peat, I came very much awake.

"This is fantastic! You definitely should put it on the market! It will do amazing things for the image of Japanese whisky!" said I, prophetically.

As it happened, I was eventually asked to become an official adviser to the Nikka company, and the honorary curator of their whisky museum in Yoichi. In that capacity, I strongly insisted that their malt whisky should be bottled and sold.

Unfortunately, and in Japan especially, there are always those who don't want to do things that are different or new. So some people said that an advertising campaign just for single malt would cost too much. I countered that they needn't spend money on advertising; writers and broadcasters like me would write about it and air its qualities on radio and television. Consequently, their malt whisky would become famous by word-of-mouth.

Another negative argument stick-in-the-muds came up with was that it would be costly to design a new bottle and label. I said they should use their regular sample bottles with a simply printed label.

Anyway, any genuine, unprejudiced whisky-drinker now knows that Nikka single malt is one of the finest whiskies in the world (and, of course, Suntory soon followed suit when they saw what was going on). And though there are purists who may be loathe to admit as much, even in Glasgow I have never found anyone who would turn down a swig or two of Japan's finest.

I had another suggestion about advertising. Commercials emphasized the quality of water, of barley, of clean air and of the surrounding nature, but nobody had really managed to show the actual time it takes to make a good whisky.

I suggested that they let me make a barrel of single malt, and to follow me through all the steps on the way — from making the barrel to spreading the water-soaked barley grain in the malting loft and keeping the barley mixed until the little seeds began to send out roots and the starch inside them was converted to maltose sugar. Then the peat furnace would have to be fired up and tended, with the heat from it stopping this process and also imparting a peaty, smoky flavor.

Next we'd get to the milling and brewing of the malted barley to produce the sweet liquid to which yeast would be added, thus converting the maltose into alcohol before this mildly alcoholic beverage was stilled and condensed twice over to produce a clear, fiery liquid of almost 80 percent alcohol.

This would then be laid to rest in an oaken barrel. Oak is just porous enough to allow the barrel to "breathe" without leaking. Over the years, 15 being just about right, the barrel would "pay" the batch's so-called angels' share of the really volatile stuff that would give a man a fearful headache, as it evaporated away together with a percentage of the alcohol.

My argument was that by the time we got the whisky bottled, in 12 to 15 years, then the elapsed period of aging could be shown in a commercial by the aging of my face and those of the experts who were teaching me how to make whisky.

We did it. We made a new oak cask and seared the inside with a gas-fired burner to turn sugar in the wood to caramel and impart a slight color and taste to the alcohol. We fired up the peat for 12 hours, because I liked "smoky" whisky such as Laphroaig, the strong-tasting Islay whisky from Scotland.

After three years we decided to switch my whisky into a barrel in which sherry had been imported, and which had then been used to mature a batch of 10-year-old whisky. This barrel would give it a smoother, more delicate taste.

To finally realize the finished product, we turned to the very first whisky still ever made and used in Japan. It was small, able to produce only one barrel, and had not been used for decades. I spent most of three days inside that copper pot with a wire brush and a hosepipe, scouring it until it was perfectly clean and shining. I was 46 then, and could just manage to squeeze in and out of the round hole. Now, at 72, I'd get stuck like Winnie-the-Pooh if I tried to do that again.

After this very special barrel of whisky had been maturing in an earth-floored, stone-walled warehouse, we drew some of it off so that a very famous British whisky expert could taste it. (Understandably, I had been visiting Yoichi to sample it a few times in the meantime, just to make sure everything was going fine.) The British expert would be sniffing and tasting about a dozen different whiskies, most of which were from Scotland, so he definitely did not know that one of the anonymous but numbered glasses would contain whisky that I had made.

When the expert tried my whisky he was visibly surprised. "This I would place in the top six whiskies of the world, but I've never had it before. It's very peaty, but not from Islay," he declared. I was chuffed.

He also said that we should hurry up and bottle it, because it was just starting to get a woody flavor (from the tannins in the oak).

We did indeed bottle it, and over the years I have shared this whisky with and given it to many people — including a few Japanese prime ministers and Bill Clinton (who sent me a very nice card). Now, 26 years later, there are just nine bottles left of the 360 we got from that one barrel.

However, as those involved in that process decades ago retired or changed positions in both the whisky company and the advertising agency, the intended commercial never got made, although we filmed every process through those 14½ years. That was a disappointment, but the downside was as nothing compared with the pleasure the whisky has given me and several hundred other people.

And better yet: My manager got a little worried along the way that Old Nic would lose his zest for life if he didn't have another barrel of whisky maturing in the warehouse, something else to look forward to. She can be very persuasive. So it came to pass that I was allowed to make another barrel. This time I cut down the duration of peat burning to six hours because, as I aged into my 60s, I was tending to prefer a milder whisky for serious drinking, although a peaty one is just right for a pick-me-up.

The second barrel of Yoichi single-malt, single-cask whisky was bottled at the end of 2012. I have tasted it, and honestly, even if I hadn't taken part in its making, I'd say it really is one of the smoothest, finest whiskies I've tasted.

It has been bottled under the name of Old Nic's Dram — and no, I don't get a percentage of its sales revenue, but the company has become one of the sponsors of our Afan Woodland Trust. And of course, they've been kind enough to present some bottles for Old Nic himself.

I wonder if they'll let me make another barrel?

We are having a party in Tokyo on Feb. 20 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Old Nic first coming to Japan; 10 years since Afan Woodland Trust was founded; and the bottling of Old Nic's Dram. Any readers who are interested in attending should email the C.W. Nicol Afan Woodland Trust at [email protected].

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.