Japan's annual slaughter of thousands of dolphins began Oct. 8 in the traditional whaling town of Taiji on the Kii Peninsula of Honshu's Wakayama Prefecture. These "drive fisheries" triggered demonstrations, held under the "Japan Dolphin Day" banner, in 28 countries. The protests went almost entirely unreported in Japan, where only very few people are aware of what goes on.

The culling, spanning a period of six months, is officially condoned as part of traditional culture, and is described as "pest control" by practitioners. However, it is the inhumane way in which the mammals are killed, by stabbing and spearing them, that especially provokes such widespread revulsion.

Taiji fishermen begin the oikomi (fishery drive) by going out to sea in motor boats to locate pods of dolphins. They then place long steel poles with flared, bell-like ends into the water and bang them to create a wall of sound that amplifies underwater and drives their prey into a narrow cove. Once there, the dolphins' escape is cut off by nets strung across the mouth of the cove. The following day -- after they have rested so, it is thought, their meat becomes more tender -- they are herded into another cove nearby where the slaughter is carried out. Much of the meat is then processed for human consumption -- even though eating it could well be a very foolhardy thing to do.

A video with footage shot at Taiji in January 2004 by One Voice, a French-based animal rights group, and other footage from a similar oikomi in Futo, Shizuoka Prefecture, by a cameraman who requested anonymity, shows dolphins thrashing about wildly as they try to escape and the water turns red.

Drive fisheries appear to be carried out in as much secrecy as possible, and the killing cove in Hatagiri Bay at Taiji is hidden between two mountains. There, a gigantic tarp is strung over the shoreline to cut off the view from land, and paths leading to the cove are closed off with chains and posted with signs reading "No Trespassing!" and "Keep Out, Danger!" said Ric O'Barry an official with One Voice.

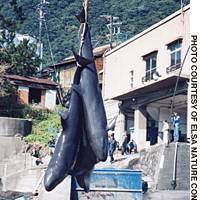

O'Barry, a former trainer of the dolphins used in the U.S. television series "Flipper," recently returned home to Miami from Taiji after shooting footage of freshly killed dolphins being lifted onto a pier in the harbor there. Speaking prior to his departure, O'Barry said that the Taiji dolphin-killers are proud of what they do, and boast of a tradition dating back 400 years. "However," he commented, "if they are so proud of this, why do they take such pains to hide their activity?"

O'Barry said he met with the local Taiji fishery group and offered them a subsidy to stop the killings, but was rebuffed and told the dolphins were "pests" that competed with the commercial fishery. Noting that there are no scientific studies showing dolphins are responsible for falling fish stocks in the area, O'Barry cited overfishing as the probable cause.

But it is not just those doing the killing who make every effort to hide it from the world. Japanese officials also strongly discourage outsiders from seeing, recording or protesting the blood-letting.

During a fishery drive on Nov. 18, 2003, two members of the Washington state-based Sea Shepherd Conservation Society were arrested by police from Taiji's neighboring town of Shingu for jumping into freezing waters and releasing 15 dolphins trapped in a net awaiting slaughter. The pair, Alex Cornelisson from the Netherlands and American Allison Lance-Watson, were held without bail and only released on Dec. 9, 2003, after being indicted and fined for "forceful interference with Japanese commerce." Meanwhile, two other Sea Shepherd members staying in a trailer park in Taiji had their cameras, film, computer and some personal belongings confiscated by police, according to an online news release from the group. Undeterred, Sea Shepherd is offering a $10,000 reward to anyone who provides the best footage of the drive fishery.

In response to allegations that the oikomi dolphins suffer from shock and die slowly, in a Sept. 19, 2005, letter to British-based animal welfare and conservation charity the Born Free Foundation, Jun Koda, Counselor of the Japanese Embassy in London, said: "In some small parts of our country we have a long tradition of consuming dolphin meat. Japanese fishermen are careful to minimize suffering as soon as possible and cause as little pain to the dolphins as possible."

Koda went on to say that the dolphin "almost instantly meets its end within a maximum of 30 seconds and does not suffer any pain."

A rebuttal from Born Free said the data in which Koda based his claim is taken from Faeroe Island dolphin hunts in the North Atlantic, which have not been subject to independent scrutiny and hence have no bearing on the Japanese culls. Koda's assertions are also countered by observers from One Voice and Sea Shepherd, who have reported seeing wounded dolphins writhe in pain for almost six minutes before succumbing to their wounds.

Meanwhile, another Japanese official was equally forthright in countering critics' objections to killing dolphins for food. In a telephone interview this month, Hideki Moronuki, assistant director of the whaling section in the Far Seas Fishery Division of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, expressed the view that, "If someone eats a cow, why should one object to a dolphin being eaten; they're all mammals."

He added, "If Australians want to eat kangaroos, we don't care. . . . Please do not care what Japanese do. . . . Dolphins and whales are part of Japanese food culture."

Furthermore, speaking in English, Moronuki expressed his view that dolphins are killed humanely in the fishery drives. Then, comparing the slaughter of a dolphin to that of a cow or a pig, he declared: "Killing is killing."

O'Barry believes this is the attitude of most Japanese fishermen. "They don't think of dolphins as intelligent, highly complex animals that love to play and interact with people," he said.

But such sentiments are not confined to welfare and conservation groups.

On April 6, 2005, U.S. Sen. Frank Lautenberg, a Democrat from New Jersey, sponsored Senate Resolution 99, "Expressing the sense of the Senate to condemn the inhumane and unnecessary slaughter of small cetaceans . . . in certain nations." The submission, currently referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations, not only cites the fact that "those responsible for the slaughter prevent documentation or data from the events from being recorded or made public," but it describes how, "each year tens of thousands of small cetaceans are herded into small coves in certain nations, are slaughtered with spears and knives, and die as a result of blood loss and hemorrhagic shock."

C.W. Nicol, the renowned environmentalist, author, whaling expert and Japan Times columnist, recently made an M.B.E. by Queen Elizabeth II, witnessed the Taiji dolphin slaughter while living there in 1978. Speaking last week, he said: "It's been a cancer in my gut ever since. It's no good to kill an animal inhumanely, and to do so is not to the advantage of Japan."

However, not all the captured dolphins are killed. Every year, an unknown number of healthy young specimens are selected and removed from the killing coves to be sold into the international dolphin captivity industry, to be kept in aquariums, trained to perform at dolphinariums or for swim-with-dolphin programs. At Taiji, those involved appear to reap rich rewards in this way, and O'Barry said he was told there that the fishery drives would stop and those carrying them out would go back to catching lobsters and crabs if they were not offered huge sums for "show" dolphins.

Echoing this, Nicol said he vehemently opposes the dolphin massacre, adding, that "dolphins not selected for dolphinariums should be returned to the sea."

However, in a further, darkly ironic twist, serious health issues would seem to surround meat from the slaughtered animals, which is available at supermarkets in Shizuoka Prefecture and Kyushu.

At present, Hiroyuki Uchimi of the Japanese health ministry's Food Safety Division explained, the provisional advisory safety levels set in 1973, and still in effect for methyl mercury, are 2 micrograms a week for pregnant women and 3.4 micrograms a week for all others, including children, for each kilogram of body weight.

But according to Tetsuya Endo, a member of the Pharmaceutical Sciences faculty at Hokkaido's Health Science University, mercury in a sample of the meat he tested in 2003 from a supermarket in Ito, Shizuoka Prefecture, was 14.2 times higher than the government's maximum advisory level. "It is terrible," he said this month.

Endo's finding was amply supported by those of a 2000-2003 joint survey of small cetacean food products sold in Japan by the Daichi College of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Fukuoka, Kyushu, the university where Endo works, and the School of Biological Sciences in Auckland, New Zealand. Published in 2005, this found that all dolphin food products "exceeded the provisional permitted levels of 0.4 micrograms per wet gram for total mercury and 0.3 micrograms per wet gram for methyl mercury set by the Japanese government. The highest level of methyl mercury was about 26 micrograms per wet gram in a food sample from a striped dolphin, 87 times higher than the permitted level." Methyl mercury is a particularly dangerous form of mercury, a neurotoxic metal.

The paper concluded, "The consumption of red meat from small cetaceans . . . could pose a health problem for not only pregnant women, but also for the general population."

Despite this -- and that Senate Resolution 99, which cites "warnings regarding high levels of mercury and other contaminants in meat from small cetaceans caught off coastal regions" -- health warnings are not posted on the labels of such food products sold in Japan.

In addition, critics of the drive fisheries claim there is little monitoring of government culling quotas, already the highest in the world. At present, these quotas set by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries -- with drive fishery licenses then issued by prefectural governments to local fishery cooperatives -- stipulate that in the current 2005/06 season, 21,120 small cetaceans can be killed, besides those selected for captivity. O'Barry estimates that "more than 400,000 dolphins have been killed in Japan by dolphin hunters over the past two decades."

O'Barry, who added that he is passionate about banning dolphin hunts, said he even reversed his position on hunting cetaceans "to be clowns" in aquarium shows after Cathy, one of the dolphins that portrayed Flipper, died in his arms. As a trainer, O'Barry said he discovered that dolphins were among the very few creatures in the animal kingdom that were not only highly intelligent, but also self-aware, like gorillas and humans, as evidenced by recognition of themselves when they saw their reflection in a mirror or watched themselves on a TV monitor.

Perhaps a similar self-awareness on the part of dolphin hunters would point a way forward. This may already be happening, as film-maker Hardy Jones of the California-based Blue Voice conservation group found last month when he was in Futo, where recently there has been a drastic decline in dolphin catches.

In a phone interview last week, Jones explained that while in Futo he heard from a source close to former dolphin hunter Izumi Ishii that "Ishii has switched from hunting dolphins to conducting 'dolphin watch' tours. So far this year he's taken 2,600 tourists, who pay 4,000 yen each to enjoy seeing dolphins in the wild."

As Jones observed, "With Ishii making more money from the tours than he ever did as a dolphin hunter, he is setting a great example for the Taiji fishermen to follow as well."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.