Takashi Nagase still breaks down when he remembers the young British man he helped torture. "I couldn't bear his pain," he says, choking back tears. "He was crying 'Mother! Mother!' And I thought: What would she feel if she could see her son like this? I still dream about it."

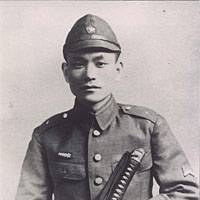

Nagase was an interpreter for the dreaded Kempeitai, military police in the prison camp made famous in the Oscar-winning 1957 film, "Bridge on the River Kwai," when POW Eric Lomax was caught with a concealed radio and map.

Neither man has ever completely recovered from what took place in the following days as Lomax was relentlessly tortured.

For the 22-year-old Signals Corps' engineer from Edinburgh, it was the beginning of a nightmare that has taken him 60 years to shake off. "The psychological damage stays with you forever," he says.

For his 21-year-old tormentor, it was the start of one of the most remarkable and courageous stories of repentance.

Lomax was beaten relentlessly and dragged broken and weak before Nagase and his commanding officer for interrogation. He remembers the officer's face "full of latent and obvious violence." But it was the "hateful little interpreter," for days intoning in a flat, inflectionless voice, "Lomax you will be killed," who he really despised.

Nagase's voice droned in his ear as he was repeatedly held down and water was hosed into his nose and mouth, filling his lungs and stomach. Lomax survived -- barely -- to spend the rest of the war in a brutal military prison, and for half a century nursed his hatred of his interrogator. "I wished to drown him, cage him and beat him," he says.

Hell on earth

Today, Nagase is a frail 87-year-old retired English teacher who says he understands the hate directed at him. "People who have been to hell do not forgive easily," he says. "And we were in hell. But I wanted to help him in some way. I searched my brain for the right English expression, and as he was leaving the camp I said to him quietly, 'Keep your chin up.' I still remember his astonished face."

The Thai-Burma (now Myanmar) Railway was one of the great evil follies of World War II, a 415-km track hewn mostly by hand through rock and tropical jungle that consumed the lives of up to 100,000 men, including an estimated 16,000 slave laborers conscripted from the ranks of the decimated Allied forces. Vast numbers of Thais, Chinese, Indians and other Asians -- nobody knows how many because records were destroyed -- also perished on the project.

The British had abandoned the plan to link Bangkok with the Burmese capital of Rangoon because they believed it was impossible, but military commanders in Tokyo revived it in preparation for the Japanese invasion of India.

By the time what became known as the "Death Railway" was completed, the line was littered with thousands of flimsy wooden crosses marking the bodies of young men from Glasgow, London, Liverpool and the like who had succumbed to starvation, disease and beatings; 60 years later some of the corpses are still held in the jungle's swampy embrace, lost forever.

Nagase, who was chosen as an interpreter because he had been taught by U.S. Methodists in a Tokyo college, remembers entering the stinking, malaria-ridden Kanchanaburi prison camp, on the railway's route to Burma, in September 1943. "It was surrounded by these brazen vultures attracted by the stench of the corpses. Men were sitting in huts with no roofs, wrapped in soaking wet blankets, near death. I still shudder when I think of it."

His halting, imperfect English was often the only conduit between the camp commanders and thousands of prisoners, and he helped interrogate many POWs. But it was the memory of Lomax that lingered.

"As I watched him being tortured and heard his cries, I felt I was going to lose my mind. I thought he was going to die, and I still remember my relief when I felt his pulse."

Journey of atonement

When the war ended, Nagase spent seven weeks locating 13,000 abandoned bodies along the line for the Allied War Graves Commission; many now lie in a cemetery in front of Kanchanaburi Station. For most, this gruesome work would be penance enough for sins committed under orders during wartime, but Nagase was only beginning his long journey of atonement.

"The work of searching for bodies changed my whole life," he says. He began to write and lecture in Japan about the horrors he had seen, harshly criticizing, at some personal risk, the Japanese military and the Emperor system that survived the war.

"It should be completely abolished," he says today. "The Emperor should apologize for what was done in his name."

He used much of his own money to build memorials across Thailand, including a Buddhist peace temple near the Tham Kham Bridge over the Kwai Noi -- the bridge spanning the River Kwai -- and to fund education programs in the area. Most remarkably of all, he has returned to Thailand 125 times, the last time in June this year, on trips that, he says, "calm my soul."

In 1976, Nagase organized the first of a series of reunions between ex-POWs and Japanese soldiers, a tense affair on the famous bridge which was overseen by Thai riot police, "just in case."

Nagase was criticized by the Japanese press for holding the Thai national flag rather than the Rising Sun that had once fluttered over the camp.

"Do they know how many Thai people were slaughtered under that flag?" he asks.

But he had to wait until March 1993 before there was a reunion on the banks of the Kwai with the tall, blue-eyed Scotsman he had helped interrogate. Although not yet ready to forgive, Lomax had been disarmed by an "extraordinarily beautiful" letter from Nagase. He had gone to Thailand not knowing what to expect, and ended up comforting a shaking, crying Nagase who simply kept saying: "I am so sorry, so very, very sorry."

The formal forgiveness that Nagase craved came later.

"I knew he had hated me for 50 years, and I wanted to ask him if he forgave me, but I couldn't find a way," says Nagase today. "So I said: 'Can we be friends?' and he said, 'Yes.' " And the old soldier who will again travel to Berwick-upon-Tweed on England's northeastern border with Scotland next month to see the man he now calls "my friend" is again wracked by sobs.

When they meet, the men will swap war stories and share their astonishment at the "utter futility" of the project that scarred their lives so profoundly.

Lomax wrote in his biography, "The Railway Man": "The Pyramids, that other great engineering disaster, are at least a monument to our love of beauty, as well as to slave labor; the railway is a dead end in the jungle. . . . The line has become literally pointless. It now runs for about 60 miles [100 km] and then stops."

A shared responsibility

Nagase has never got over his bitterness at the waste of lives, and he believes, controversially, that young Japanese today share responsibility for what happened. In July this year, he astonished a group of British high-school students on a trip to Japan sponsored by the Imperial War Museum in London by tearfully apologizing to them and demanding that a Japanese student do the same. "This is not a problem of our generation," said the bewildered Japanese, a reply that infuriates Nagase.

"It is not a generational issue," he says. "The shame belongs to the whole Japanese race."

Needless to say, he is disgusted by attempts by some nationalist scholars and politicians in Japan to rewrite history. "The textbooks they have written contain the same things as we were taught in school in the textbooks in the leadup to the war. It is unforgivable."

And he has no tolerance for Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni Shrine, the war memorial that he and Lomax visited together when the Scotsman came to Japan. Lomax was astonished to see a monument in the shrine to the hated Kempeitai, saying, "It is like seeing a memorial to the Gestapo in a German cathedral." Inside, they found an "immaculate" C56 steam locomotive from the Thai-Burma railway, with no mention of those who died constructing the line; Lomax calls it a "monument to barbarism."

"Koizumi is a fool," spits Nagase. "I don't care who I say this to. And why are the newspapers now writing that the war was good? What do they think the Japanese Imperial Army was doing in East Asia for 15 years? Why don't they listen to what other Asian people are saying? Sometimes this is an odd country."

Although he says he is considered a "traitor" in Japan, Nagase also frequently criticizes the United States. "What the Americans are doing in Iraq is not good," he says. "In war, people identify exclusively with their country. It makes people crazy. There have to be other ways of solving problems."

At 87, Nagase knows his time is short, and he desperately wants the railway declared a U.N. World Heritage Site before he dies. In November, despite a dangerously weak heart, he will cycle with a group of Japanese peace campaigners along the remains of the line as part of his campaign. He has cultivated good ties with Thai government officials and won the support of several embassies, but the U.N. designation is controversial.

There is little official support in Japan for a memorial to one of history's most barbaric episodes, and some veterans are still reluctant to embrace their former captors in a joint campaign; others believe that the railway should be allowed to sink back into the jungle. A 1987 commercial plan to renovate the line was criticized by the former Allied countries and withdrawn.

British Foreign Office spokesman Dan Chugg said the British government had not been formally approached about the move, but any response "would depend very much on the views of the veterans about how we might feel about the proposal. If it comes up we would talk to veterans groups and take it from there. Because it is not a site in the U.K., we are simply an interested observer."

Badge of courage

For his part, Lomax is unequivocal. "He has my complete support. This is very important to him."

After 60 years of campaigning, to make up for less than two years' service in the Thai prison camp, those who know Nagase say his relentless search for redemption is humbling and awe-inspiring.

"He is so courageous," says Keiko Tamura, who runs an organization that helps locate former allied POWs in Japan. "The people who fought in the war forgot their humanity, so it is a long battle to get them to see each other as human beings again. That's what he does.

"He is often asked why he continues, and he says, 'It is so we won't forget those who died.' "

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.