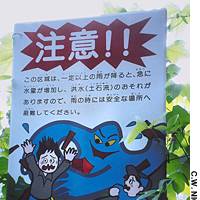

Every summer in Japan there is news of a few children drowning in rivers, and the message that comes from the media with those tragic stories is that rivers are dangerous and children should not go near them.

Did any of you play in a river as a child? Isn't it a wonderful memory? In my first few years in Japan in the early 1960s, I thought that summer in the countryside was heaven for children. So many beaches and warm seas full of fish, so many clear running rivers with jade-green pools and places to jump or dive from!

Yes, rivers can be dangerous, but even more so are the roads that run by schools -- the difference is that we try to teach children as early as possible about the dangers of crossing a road. At primary school in Britain, we had a big uniformed bobby come and drill it into us to stop at the curb and then look left, right and left again before crossing. Even so, at the age of 6, I stepped out in front of a bus. The bus squealed to a stop, and I was saved, but I'll never forget that look of horror, soon changing to anger, on the bus driver's face.

Children living close to nature learn about the fun, the challenge and the peril of rivers from their peers. I especially recall spending an evening by a river with some children in Rwindi, in the Virunga National Park. It was back in March 1986, in a country then called Zaire -- now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Our hotel had separate thatched rondavels for guests, and we were advised not to go out after dark because there were hippos grazing and lions roaming all around. Certainly, I heard them all night, as well as the yipping of hyenas.

There was a school for the children of rangers and other park workers, which we visited. As in other country schools we went to, there were no notebooks for the kids, who wrote with stubs of pencils or bits of charcoal on pieces of old cardboard or whatever they could find. They were taught in French, but all the kids we met could speak a native tongue, and a few could speak English.

One evening after school, myself and photographer Mike Stanley followed the park children, aged 6-12, down to a small river (whose name I've lost and can't find on the map, but I believe it is a tributary of the Semliki River). They all carried containers to fill with water to take home.

Yells and splashes

Once the children got to the river they first filled their cans, buckets and jugs. Then they stripped off to wash the clothes they were wearing. These they hung out on branches to dry. Chores done, the children then jumped into the river with yells and splashes. The bigger boys swam out to deep pools with pretty strong currents. Girls and smaller kids stayed and played in more shallow, safer water.

Meanwhile, one older boy was left on the bank, looking upstream and downstream. When I asked him what he was doing, he said, "Keeping a lookout for hippos and lions."

"What if you see one?" I asked.

"I yell to the others to get out of the water if it's a hippo, and to all get together if it's a lion."

These children were all looking out for each other, the older ones protecting and teaching the younger ones. They were looking out for us, too. When I went to touch a flowering cactus, a boy grabbed my hand. "No, it's poison, don't touch!" he said.

We played a game with the kids, getting them to imitate the calls of animals and birds they knew. They could imitate hippos, lions, leopards, hyenas, wart hogs and so on wonderfully well. They asked us to imitate an animal we knew. I did an imitation of a wolf, which they all recognized immediately, even though there are no wolves in their environment. No television either. Then I imitated a sea lion, which puzzled them for a while, until one boy's face lit up with a grin.

"It's a seal," he said, in French. Not bad, kid, I thought.

As the shadows lengthened, one of the older girls called the children together. They dressed hurriedly, picked up the water to carry home, and all walked back to their homes in a tight little group. There was no adult supervision.

In our Amway-sponsored "One by One" program for disadvantaged children in Nagano Prefecture, we have a summer camp. The children spend most of the time in the woods, but half a day is spent on the Torii River, which runs just outside our Afan Woodland Trust office (and my study-dojo) here in Kurohime.

I have written before in this column of how the river burst its banks in a raging flood in July, 1995, and of a battle I had with the authorities, who wanted to do their usual job of plastering the banks with concrete and creating a series of ugly dams. I got a lot of support for this fight, and I called in my friend Shuubun Fukutome from Kochi in Shikoku. He is the leading Japanese expert in techniques of river construction that as closely as possible approach nature.

Eddies, riffles and pools

The outcome was that construction plans were drastically altered to take into consideration not only flood-control safety, but also habitat for fish, aquatic insects and birds. Natural boulders were used more than concrete, creating eddies, riffles and pools. Very soon after construction, willows, reeds and rushes began to grow back. In the 10 years since then there have been several floods, but no trouble. Both Mr. Fukutome and our local construction company, Takeuchi Construction Co., received prizes from the Environmental Agency for this work. River habitat suitable for wildlife in Japan is, generally, safe habitat.

Since this construction work, the river in front of my place has also become an excellent habitat for children, as well as for fishermen and artists.

The little bullheads have come back, and anglers fish for char. Herons hunt the river, and I've spotted kingfishers too, though not as many as there used to be before the construction. In order to get the heavy equipment used to maneuver big boulders into place, they made a gentle sloping access way, cobbled with stones and gravel. Now, this affords easy access for people, too.

It's not perfect. Before they built the dams on the Chikuma and Shinano rivers, our little Torii River up here in the mountains had an unimpeded link to the Sea of Japan. Salmon and char migrated up to the Torii and its highland tributaries to spawn. That's well within living memory. Maybe we can one day re-open that natural link.

What I want to say though, is that on hot summer days, it is the most natural thing in the world for children to play in streams and rivers. We have made it dangerous for them, by polluting, by building dangerous concrete obstructions, by garbage dumping and, just as serious, by cutting of children's links to nature.

Now, if children are to play in running water, we have to make sure that the water is clean and safe, and that until children can pass on river lore to each other, responsible adults are there to guard and instruct them.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.