These are hard times for Japan's construction workers. The days when they were forever taking flak for digging up roads and causing traffic chaos, or teetering on the edge of scandals as they built yet more roads and bridges into the middle of nowhere are now long gone.

Well, if not gone entirely, at least such spendthrift ways have been scaled back. In fact, land ministry data shows that the private and public sectors spent 52 trillion yen on construction projects in fiscal 2004 -- a 40 percent fall from the peak in 1992.

Whereas many regard this as a return to sanity, for local economies that rely heavily on construction, it often simply means lost jobs and lower wages. The city of Furukawa in Miyagi Prefecture, a traditional farming stronghold north of Sendai, is no exception.

Nobuyuki Ishigamori, the second-generation owner of a construction and civil engineering firm there, gripes that the area's contractors are now quoting cut-throat prices when bidding for contracts. "This only worsens our prospects of survival," he says grimly.

Is there a way out without returning to the old days?

In 2003, Ishigamori came up with a possible solution -- and a big gamble -- when he and the heads of four other local construction companies set up a new company to supply and sell what they reckoned would be the Next Big Thing: organic rice.

Rice?

"Farming is sublime," said the 51-year-old Furukawa native, who admits to having been a complete novice in the field of agriculture until two years ago, as he slouched one day recently on a sofa at the single-story makeshift office of the agricultural company Hearoc (pronounced "hero"). The building is next to a concrete-mixing plant that Ishigamori also owns.

"Food is what shapes our lives," he declares with the passion of a true convert. "We must leave healthy, chemical-free food production for our offspring."

To that end, Ishigamori has involved in his venture Minoru Ishii, an award-winning organic rice farmer whose produce fetches the highest price at high-end supermarkets in Tokyo. Their goal is to spread the idea that the way rice is grown -- not just its variety or place of origin -- can give it just as much "brand value."

It's been decades since Japan moved out of farming and started making cars, electronic goods and computer games. But these days, many companies, both large and small, especially in construction, are pinning their greatest hopes on farming as a moneymaking venture -- and a source of jobs.

Along the way, they are helping to breathe new life into the nation's heavily-subsidized, inefficient and uncompetitive agricultural sector.

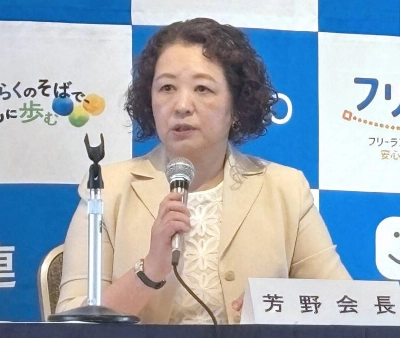

According to Masako Yoneda, secretary general of the nonprofit organization Partners in Sustaining Architectural Technology and Skills, who has spearheaded this "back to farming" movement, more than 120 construction firms are now also growing rice, tomatoes, mushrooms, blueberries and other crops.

And, surprisingly enough, the transition has been relatively smooth, Yoneda notes, because agriculture and construction are not totally unrelated to each other.

Before Japan's postwar industrialization, most of the population was living off the land. Then, during the 1955-73 period of rapid economic growth, many country people also picked up construction work on the side -- just as they were again able to do in the bubble era of the late 1980s -- she says.

While cash-strapped contractors have recently turned to other sources of income as well, such as operating nursing homes and waste recycling, they find it easiest to switch to farming, the researcher observes. "Farming poses the least psychological barrier for construction firms," she said. "It's therapeutic to work with nature. Plus, many construction workers have experience on farms as, for example, small paddies have been 're-zoned' into larger, more economical units."

Not just a grassroots move

While Hearoc is an example of a grassroots move into "agribusiness," primary industries have recently been sparking the interest of big corporations, too.

One of these is the major staffing agency Pasona Inc., which sees farming not so much in "sublime" terms as high-tech ones.

In February, the company, which has 400,000 people registered and ready to be dispatched to companies nationwide, debuted a vegetable garden in the basement of its head office right in the middle of Tokyo.

Dubbed O2 the garden showcases various lighting, watering, air-conditioning and other technologies that allow vegetables to grow without soil or natural sunlight.

"On the surface, it's about agriculture," says Yasuyuki Nambu, CEO and president of the Pasona group. "But the way we are doing it, it's about high-tech."

In the fall of 2003, Pasona also sent a group of middle-aged retired and working sararimen as farming interns to a village in Akita Prefecture, then followed that up by sending twenty- and thirty-something freeters to the same village in 2004. All this to make people more interested in farming as a career, and to further its aim to offer farming jobs to city dwellers.

Of course, it's not entirely straightforward for either companies or individuals to enter this heavily-regulated sector.

In Japan, companies not already connected with farming the land are prohibited from using land designated for agriculture unless they engage in it in a way that does not draw on the land itself -- such as hydroponic crop production or raising fowl or pigs indoors. Alternatively, they may set up another entity according to very specific guidelines and then apply for "agricultural corporation" status. If this is awarded, they can engage in regular farming. However, the rules governing agricultural corporations make it hard for them to raise capital, and agricultural lenders are skeptical of funding newcomers with no proven track record in farming.

In addition, Ishigamori says that many of the area's farmers are afraid of taking the risks to deal with Hearoc. In practice, this either means Hearoc entering into a contract with them, ensuring they grow rice organically, then buying their crop, or leasing farming land and then cultivating the rice itself using underemployed construction workers as the labor force.

Nonetheless, as limited as such developments may yet be, Yoneda believes a momentum is developing in this line of business. She is expecting regulations to be eased later this year to make it simpler for reform-minded construction companies like Hearoc to move into agriculture.

"Many traditional farmers have lacked the awareness that agriculture is a sublime sector," Ishigamori said. "Many of them have happily and aggressively adopted agrochemicals just to make the product look good. To me, it looks like they are selling their souls to the devil."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.