The first time he met her she told him everything, but he wasn't listening to the words.

"You have a very beautiful voice," he said.

"Thank you," she replied, lowering her eyes, "but it's not really mine."

Later, soothed sound of the driving rain, he was able to think about it. He realized that she was right. But that was much later.

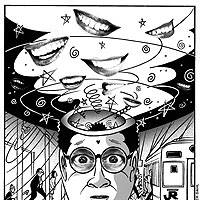

He had heard the voices all his life. When he was growing up, there were just a few, soft and maternal. But after he left home and came to live in Tokyo, there were swarms of disembodied women's voices filling the air above him, telling him that the train was approaching, warning him to step back from the edge of the platform, reminding him not to forget his umbrella. The same phrases everywhere, repeated endlessly -- a permanent feature of the landscape -- like the lights, the crowds and the eyes that caught his glance and quickly looked away in this city with its back turned toward him.

Had you asked, he could not have told you why he had begun hearing them differently. Or when he had started listening. And then, finally, seeking them out.

But once he started listening -- really listening -- the chorus of furies gave way to a host of soloists. There was the voice near the station with its long, drawn-out vowels and sudden changes in pitch that made it sound alien almost like Chinese. And then the amateur at the sauna, uncomfortable with all the long, formal phrases. And the one on the subway platform downtown, the cooing voice with the faint smile in it.

All of them were different now, and he could hear the regional accents, picture the mouths, the thickness of the lips molding the sounds that emerged from the loudspeaker. Someone with a name and a history. Someone to compare to all the others.

What he could tell you, and very precisely, was when he began collecting them.

He now had dozens on tape cassettes: department-store elevator operators describing the kind of products for sale on each floor, TV weather girls heralding the beginning of the rainy season or warning of approaching typhoons, bus guides reciting lists of place names: "Next stop: Central Hospital . . . Next stop: Metropolitan Sports Center." He had noted the date, time and place on a small label attached to each cassette.

When they asked, he would tell the people he worked with, or curious acquaintances, or uniformed subway patrolmen suspiciously eyeing the young man standing on tiptoes beneath the loudspeaker, one arm held high, a microphone in his hand, that it was his hobby. Some people collected stamps or tropical fish. He collected voices. What was so strange about that?

"Nothing, I guess. I collect voices too," said Mochizuki, his boss at Crystal Recording Studios. "Placido Domingo, Maria Callas, Misori Hibari; opera, enka, canzone; individual, expressive voices making beautiful music. Not that stuff. You might as well record someone reading the telephone book. What's so interesting about subway announcements?"

"I don't know. It's just . . . It's a little hard to explain," he answered, but thought: All voices are individual and expressive. That's precisely the problem.

"Well, there is no accounting for taste, right?" Mochizuki concluded.

"Right," he said, smiled, and knew no one would understand that it was just those individual qualities that he spent so much time and energy erasing from his voices late at night in the studio after everyone had left.

He was searching for something else: a voice that was warm and feminine and completely empty, a void he could settle into like a soft, deep pillow. So he made his copy, cleaned the signal of background noise, put it on endless replay and listened over and over.

With the exceptional few, he could imagine something in him moving within the metal, into the wires, upstream through the circuits to the shivering magnetic pattern racing past the playback head. But even when the mechanism seemed to disappear, when he achieved that mysterious quality called "presence," there was always a moist mouth at a microphone, someone with bad teeth or perfect teeth or too much lipstick, someone with a small mole near her upper lip. Someone.

That night he decided to work on three samples he had collected the previous weekend.

Earphones in place, he played the first one, adjusting the speed, using the filters, equalizing. But finally something personal remained: a hint of bright summer mornings in the suburbs, of plucked eyebrows and neatly pressed handkerchiefs taken from drawers filled with the scent of lavender.

He listened to the next one, began the usual procedures -- and suddenly became very excited. He stopped, looked once around the room, lit a cigarette, took one long, deep drag, then quickly put it out.

This time he bent over the console, increased the speed slightly, set the switch for infinite REPEAT, closed his eyes and pressed PLAY. And this time the voice came warbling through the wires, singing its standard song over and over, each word a string of liquid syllables, each syllable unfolding within him, brushing away all meaning, opening a silent space beyond language, beyond sound.

The next thing he felt was the damp pressure of the earphones, sweat building up inside. He pressed STOP and slumped forward, exhausted.

It would have been easy enough to find the woman who had made the recording. He knew the studios that did that kind of work. He could have made inquiries, but he hesitated as if waiting for permission. It came on the day Mochizuki asked him to find someone -- a woman -- to record the Japanese instructions on a series of English conversation tapes Crystal Studios was producing: "Listen to the following conversation"; "Repeat the following sentences"; that sort of thing.

He made the necessary phone calls and, yes, his friend Kuroda at Toyo Sound knew her.

"That's cute little Kuri. Nice voice but a bit too flat for my taste," said Kuroda.

He almost winced at the familiarity.

"Kuri?"

"Yes . . . Mikka Kurimoto. She's a receptionist at Mitsuba Pharmaceuticals, at the head office in Kanda. I think she still does part-time work. You want the phone number?"

As he took the scribbled memo from Kuroda, there was a tiny white hot-hot spark that loosed a spool of images: him, wooing her, telling her how much he loved her, mentioning, almost as an afterthought, how special her voice was -- the one she used for announcements -- how soothing the tone when she spoke that way, how happy hearing it her made him.

Her, falling for him and playing along, coming to live with him.

Him, encouraging her to use her voice. First, on all the short, ritual phrases: "Wake up, dear." "Don't forget your umbrella." "I'm home." "Goodnight." Rewarding her with gifts. Hugs, kisses when she said them just right. The two of them, making love. Her, crying out in that voice. And afterward, him, telling her how much he loved her.

Heat rose to his face. Cartoons, that's all they were. What am I thinking of! What if she turns out to be fat and very ugly? But Kuroda had said cute, little, hadn't he? And anyway . . . it isn't really her I'm interested in, he told himself. It isn't personal. It's her voice.

He climbed the long flight of stairs out of the subway and back into the dark gray damp of the rainy season. How he had hated it when he first came to live here: waking at 7:30 in an incandescent twilight, the clammy lukewarm sweat, the faint moldy smells everywhere, and the people, even more short-tempered than usual. Everything he hated about Tokyo amplified.

He made his way around the oily puddles spattered with electric rainbow reflections from the neon signs. It was late afternoon when he entered the headquarters of Mitsuba Pharmaceuticals and slipped his umbrella into the rack. In the lobby, there were still a few people waiting to be paged. He noticed the two young women in blue uniforms, answering phones and taking messages at the reception desk, but he did not approach them.

Then he heard that voice: "Paging Mr. Onodera of Heisei Chemicals. Please come to the reception desk."

But it was different, slightly lower, and the speakers had added such a fuzzy overtone that it didn't sound like the right voice after all.

A large man in a suit and tie approached the desk, was handed a memo, and walked off toward the elevators. Something was wrong, but he decided to make his move anyway.

He went up to the desk. "Excuse me. Are you Mikka Kurimoto?"

"Yes?"

"You have a beautiful voice."

"Thank you," the young woman replied, lowering her eyes. "But it's not really mine."

"I'm sorry, what . . . ?

"I mean I don't talk that way all the time. It's my 'stage voice' -- that's what we call it. Oh, I'm sorry, may I help you?"

"Yes . . . Well . . . Actually it's your voice I'm interested in. I mean . . . I work for a recording studio and we need someone . . . "

"A job?"

"Yes. I got your name from a Mr. Kuroda at Toyo Sound. Here's my card. Perhaps we could meet sometime soon."

"I get off in about 20 minutes, if you don't mind waiting."

"Not at all. Is there a coffee shop somewhere nearby?"

They got a table near a large window that overlooked the rainswept street. She ordered milk tea; he, iced coffee. They made small talk. He asked her about herself, where she was from.

"Yamanashi, and I'm really tired of that idiotic joke about how strange it is to call it Yamanashi when there so many mountains there are."

"So many mountains?" He was barely listening.

"Yes. Oh, come on! You know yama means mountain; nashi means none. Yamanashi: No mountains.

"Oh, that one." A stupid pun.

She continued talking. The rain running down the plate-glass window seemed to enclose her on all sides. He tried not to listen, tried to imagine her lips moving silently like the lips of a fish in an aquarium, but he knew she had told him the truth. That voice wasn't really hers. It was his something he had made for himself, splicing and editing, reducing the noise, raising the pitch until it was just right. Just right for him.

"What do you need me for?"

He woke to her sitting there before him, patting the perspiration from her chin with a white handkerchief bordered in violet flowers.

"I need you . . . for some recording work," he answered, and suddenly felt so light, so airy, so much like laughing. He realized that he didnt really need her, but that he would hire her anyway.

Embarrassed, he looked away and began searching his pockets for a map.

"Here's our studio. You see? We're right near Yoyogi Station. Oh, and the job. We'd like you to work on some English conversation tapes."

"I'm sorry but I don't speak English."

"No, no," he laughed softly, grateful for the opportunity to console her. "We'd like you to do the Japanese instructions: 'Listen to the following conversation'; 'Repeat the following sentences' -- that sort of thing."

"Oh, that sort of thing. Well, I'm usually free in the evenings or on Saturdays. Would next Saturday be convenient?"

He made a note in his appointment book. They talked for a bit more, then he paid the bill and she said she had to rush off.

That night he had dinner late, drank a bit too much, then got on the subway. As he changed trains at Omotesando, he noticed a large glass booth with a flower arrangement in it. He had passed that booth before. Every few days a new arrangement would appear. It was a kind of advertisement for an ikebana school. This time he stooped and looked. There were a few stalks of purple hydrangeas with leaves, some small carnations and thin blades of grass, all casually arranged in a gray container. Rainy season. Hydrangeas were blooming everywhere now, big bushes of them in dark gardens and under the cold metallic light of street lamps. But here, there were just three blossoms, neatly trimmed of most leaves so you could see their stems, and tiny, bright-pink carnations against the green. And the grass, like rain cascading from the cloudy, translucent glass vase. He could not take his eyes off it. Whoever did this, he thought, must hate the rainy season very much, enough to make this enchanting weapon. The purples and greens, the curious, meandering stems, the brilliant spots of electric pink, the gleaming grays and falling rain in a space as empty as his solitude, a space to fill with dreams that must eventually fade like the flowers they are, like the season itself.

Like a voice fading back into silence.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.