The year was 1841. Japan was still the closed country it had been for two centuries by order of the feudal Tokugawa Shogunate; for a Japanese to go abroad, or return from abroad, were capital offenses. The arrival of U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four black-hulled steamships in Edo Bay -- and the regime change they would soon usher in -- was still more than a dozen years ahead.

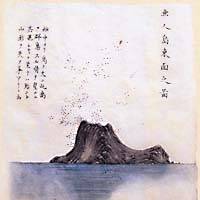

In January of that year, around the same time as young Herman Melville sailed from Fairhaven, Massachusetts, as a greenhorn aboard the whaling ship Acushnet, three fishermen and two teenage boys from Tosa (present-day Kochi Prefecture in Shikoku) were shipwrecked far out in the Pacific. It was their good fortune, however, to make it by dinghy to a small volcanic island 600 km south of Edo called St. Peter's (aka Hurricane Island or Torishima Island). There, several months later, they were rescued by the John Howland, an American whaling ship from New Bedford, Mass., across the Acushnet River from Fairhaven, under the command of one William H. Whitfield.

Among the five Japanese, the youngest was a 14-year-old from the village of Nakanohama. After the whaler docked in Hawaii and disembarked the castaways in Oahu, it fell to this boy -- called Manjiro -- to become the first Japanese ever known to visit the United States.

While the four others all chose to stay in Oahu, Manjiro -- who, despite having received no formal education at all, apparently impressed Capt. Whitfield with his intelligence -- returned to Fairhaven aboard the John Howland. He was not to see his native land again until 10 years had passed.

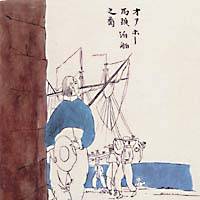

Now, just 150 years after Japan and the United States inked the epoch-making Kanagawa Treaty of March 31, 1854, which first pried open the shogunate's closed door, English speakers can for the first time read Manjiro's own account of his unique and astonishing "lost" decade. This is thanks to the U.S. publication by Spinner of "A Brief Account of Drifting Toward the Southeast," a translation of "Hyoson Kiryaku," a Tosa court's official report on the adventures of Manjiro and his companions. The report, compiled in 1852, was illustrated in color by a scholar/artist who interrogated Manjiro and drew based on his descriptions. There are also illustrations by Manjiro himself.

As the only Japanese with firsthand experience of the U.S., after his return to Japan in 1851 Manjiro was minutely cross-examined to extract for the shogunate's benefit all the information he had about this unknown entity across the Pacific.

However, Manjiro's revelations are also believed to have fired up people like Sakamoto Ryoma, Katsu Kaishu and Yukichi Fukuzawa -- key players in the movement that would set feudal Japan on a course of pell-mell modernization.

In preparing this first illustrated English rendering of Manjiro's testimony, translators Junya Nagakuni and Junji Kitadai -- who like Majiro hail from Kochi Prefecture -- said their main aim was to enlighten non-Japanese about someone who played such a significant part in the development of U.S.-Japan relations.

However, Kitadai -- a retired TBS broadcast journalist whose career included long stints in America -- said numerous challenges were presented by the transcriptions left by samurai Kawada Shoryo, the interrogator of Manjiro and his two companions. (Of the four shipwrecked sailors left on Oahu, one died on the island and one chose to remain there.)

Among these was the difficulty of interpreting some of Kawada's strange katakana transcriptions of foreign words, "since he had some knowledge of Dutch but did not know English at all -- while Manjiro did not know Japanese letters and his English was Yankee English he learned as a whaler." Additionally, Kitadai said, the original text was in archaic, 19th-century Japanese "that is like translating Chaucer into readable, contemporary English."

Not only that, but putting Japanese expressions of whaling, nautical and other technical terms into correct English was also difficult, Kitadai said. "But in this regard, Melville's 'Moby Dick' was very helpful."

With all these obstacles overcome, this translation of "Hyoson Kiryaku" -- based on a copy of the original completed just nine months before the arrival of Perry's "Black Ships," as the original is missing -- tells how, in November 1841, Manjiro parted with the four other fishermen, who remained in Hawaii, and joined the crew of the John Howland, which arrived at its home port of New Bedford in June 1843.

After that, Manjiro -- who had come to be called John Mung on the whaler -- did a "homestay" in Fairhaven, where Capt. Whitfield had his house, and was educated in Fairhaven and New Bedford from 1843-46, by which time he was 19. During that formative period of his life he learned English, mathematics and navigation at Louis L. Bartlett School of Mathematics, Surveying and Navigation. In New Bedford he was also apprenticed to a cooper, where he learned to make barrels for whale oil.

Finally, in May 1846, Manjiro joined the crew of a whaler called the Franklin as a steward in charge of provisions. In the course of what was to be a 40-month voyage, the Franklin made stops in the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands off West Africa, before rounding the Cape of Good Hope and crossing the Indian Ocean to reach the Pacific where, after stopping at Oahu, it headed back west, round the Cape of Good Hope again, before returning to New Bedford in August 1849. In the course of that voyage, too, after the captain had a mental breakdown in February 1848, Manjiro was promoted to sub-captain of one of the four whaling boats, each manned by six whalers, on which he became the harpooner.

Altogether, the Franklin caught around 500 whales that produced thousands of barrels of valuable oil. Manjiro received $350 in pay.

Clearly fired by a spirit of adventure, Manjiro then heard about the gold rush in California. That October, he and a friend named Terry embarked at Fairhaven to earn their passage to California as crew members on a ship called the Stieglitz. The two arrived in California in May 1850 via Chile, after going around Cape Horn. In California, where they saw a steamboat and a railroad for the first time, Manjiro and his friend went to Sacramento before heading for the gold mines in the North River area of the Sierra Nevada.

There, in around 70 days, Manjiro earned more than $600. With that enormous stash, he decided to go to Oahu to pick up his Tosa shipmates and return home to Japan.

After paying $25 for the voyage to Oahu, he left there with two of the four castaways in October 1850. In January 1851, Manjiro, now 24, and the two arrived in the Ryukyus, from where they were taken to Satsuma (now Kagoshima), before being taken in September to the magistrate's office in Nagasaki for the investigation.

Having evidently decided that Manjiro and his companions were neither spies nor willful escapees from shogunal Japan, the trio were eventually released by the Nagasaki magistrates and made it home to Kochi in July 1852, where they underwent a final interrogation.

Undoubtedly, as well as listening intently to what Manjiro had to say, his inquisitors must have been intensely interested in the 1846 English world map he brought back. Far more accurate than any map in Japan at the time, it was diligently copied by Kawada, who had Manjiro translate the words on it for official use.

That, though, was far from being the final eventful chapter in Manjiro's life.

After Perry's flotilla arrived in Edo Bay in July 1853, the Tokugawa Shogunate summoned Manjiro to Edo to learn about the alien U.S. from him. Then that December, in token of his usefulness, the former poor fisherboy from Shikoku was elevated to the rank of jikisan, a samurai in the direct service of the shogunate. In this capacity, Manjiro undoubtedly cast invaluable light on a world almost beyond his country's ken, in the process helping to pave the way for the momentous decision to end the centuries-long, closed-door sakoku policy.

Indeed Kitadai -- who has studied Manjiro for more than 40 years -- is in no doubt that he occupies a significant place in the history of the formation of the modern Japanese character.

"Manjiro was the first Japanese who lived as a professional in an international labor environment," Kitadai says. "For more than half his time away from Japan, he experienced life aboard a whaling ship as described by Melville."

In addition, Kitadai believes the atmosphere of New England -- where New Bedford was a liberal town renowned as an abolitionist center and for harboring runaway slaves from the South -- greatly influenced Manjiro's outlook on life.

"Living in that atmosphere," he said, "Manjiro absorbed individualism in the good sense of the word. Through living alongside Americans, he learned the American way of life. He also mingled with people of many races who worked aboard whaling ships," Kitadai says. "So when he returned to Japan as John Manjiro, not as Manjiro of Nakanohama, he had experiences and ways of thinking his contemporaries could not have even imagined."

Some, though, thought they could -- and what they imagined, they didn't like. Hence on his return to Japan, Manjiro was forced to undergo fumie -- treading on a bronze plate of the Madonna and Child to prove that he had not become a Christian. This he duly did, though in Fairhaven, Manjiro had attended services at the Unitarian Church.

"It is impossible to tell whether he became a Christian," Kitadai says. "But I think he was influenced by Christian thought. The word God appears many times in his writings. And the Bible he used has also been handed down."

Whether Manjiro was a Christian at heart or not, Kitadai suspects that when he became a samurai he must have experienced severe reverse culture shock, if not a complete identity crisis.

"Manjiro entered into the samurai's world of rigid social strata, which was completely different from the American way of life he had experienced, or the abject poverty in which he was raised. He must have had intense psychological conflicts while adjusting to samurai society."

Manjiro must have weathered these inner storms well, though, because when Perry returned to Edo Bay in February 1854, Egawa Tarozaemon, Manjiro's superior, suggested that he be included in the team to negotiate with Perry. The idea was not acted upon.

"Even if he had joined the team, he would not have been of much use," Kitadai said. "Unlike samurai intellectuals such as Yukichi Fukuzawa [a far-sighted student of Western civilization and the founder of Keio Gijuku, predecessor of Keio University], Manjiro lacked basic knowledge of the Japanese language or classical culture familiar to all samurai, and may have been unable to express ideas as required."

Nonetheless, stupid he was not. As well as teaching English to young samurai, in 1857, by order of the shogunate, he completed the first Japanese translation of Nathaniel Bowditch's "The New American Practical Navigator" -- so introducing scientific navigation methods to seafarers who until then had mostly relied on visual observations. Then, two years later, he completed Japan's first English textbook, titled "Eibei Taiwa Shokei (A Shortcut to Anglo-Japanese Conversation)."

That same year, 1859, the irrepressible Manjiro -- one of whose dreams was to introduce American-style whaling to Japan -- was appointed captain of the whaling schooner Ichiban Maru. His vision, though, never came to fruition.

In 1860, however, both Manjiro and Fukuzawa were aboard the steamship Kanrin Maru, the first ship under Japanese command to cross the Pacific, as part of a shogunal delegation to the U.S. Although Manjiro's status was that of official translator, undoubtedly his navigational and seamanship skills came in handy, too, when the ship was caught in violent storms and heavy seas midway across.

Meanwhile, Japan itself was in turmoil as the Tokugawa Shogunate teetered before finally falling in 1867. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Manjiro taught English at Kaisei School, forerunner of the University of Tokyo.

In 1870, Manjiro made his last great foray onto the world stage. This was when he was included in a government mission to observe the war then being fought between Prussia and France.

While on this mission, Manjiro managed to make an overnight visit to Fairhaven, during which, at age 43, he had his last meeting with Capt. Whitfield, who was then 65. Manjiro apparently retrieved his Bible during this visit.

After he suffered a mild stroke the following year, he refused to accept any more public duties.

Despite this, Manjiro's contribution to Japan lives on to this day.

Perhaps his main contribution, Kitadai believes, was that he conveyed the idea of individualism, a spirit of social and human equality and the concept of the U.S. democracy to people who became leaders of Japan's modernization efforts.

Foremost among these were Fukuzawa and Sakamoto Ryoma, the low-ranked samurai from Tosa who played a key role in overthrowing the old regime by helping to forge an anti-shogunate alliance in 1865-1866 between the erstwhile rival Satsuma and Choshu domains. Though he was assassinated a year before the Meiji Restoration, Sakamoto is said to have been introduced to the idea of democracy through "Hyoson Kiryaku."

For his part, Fukuzawa learned English from Manjiro. Their closeness is clear, Kitadai maintains, from the fact that in San Francisco in 1860, Manjiro took Fukuzawa to a bookstore and the two bought a few copies of Webster's English Dictionary.

"Manjiro's influence was broad and far-reaching," Kitadai said. "As an individual, he enjoyed good fortune. But he was also a man who cut his way through fate."

Manjiro married three times, the first time producing a son and two daughters before his wife died at age 24. This tragedy is believed to have led him to ensure their son, Toichiro, became a doctor. His second marriage, which ended in divorce, yielded another two sons, and his third marriage two more.

According to Kitadai, the once poor and shipwrecked fisherboy would always have bread and coffee at breakfast (or sweet green tea if coffee was unavailable).

On Nov. 12, 1898, Manjiro had his usual breakfast. But that afternoon, he suffered a brain hemorrhage and died in Tokyo. He was 71.

Today, a great-grandson of his, Hiroshi Nakahama, lives in Nagoya. Like Toichiro, he is a doctor.

Nakahama, 75, believes Manjiro's greatest contribution to Japan was that he brought back from the U.S. the Christian concept of love of one's neighbors -- a concept which the doctor says did not exist in feudal Japan.

"Manjiro learned to 'love thy neighbor' -- to help people in need without seeking reward -- from what Capt. Whitfield did for him. That was an object lesson," Nakahama said. "Manjiro put that into practice after he came back to Japan."

There are biographical accounts saying that the jikisan Manjiro was often seen giving money or items to beggars, or giving leftover food to the needy.

Perhaps most remarkable is that the Nakahama and the Whitfield families have been in touch with each other through five generations through correspondence and visits. Just last week, Nakahama received a letter from Robert Whitfield, a great-great-grandson of the captain, telling him there is talk of building a replica of the John Howland for display in New Bedford or Fairhaven. The Nakahamas plan to visit the U.S. to meet Robert in June.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.