Have you ever considered making your family tree?

Here in Japan, butsudan (family altars) in many homes mean that ancestor appreciation is a part of daily life, and annual festivals such as New Year's Day and Bon put the focus on family members both living and dead.

But the compilation of a family tree is another matter entirely; one that requires a considerable investment of time and money.

However, the rewards can be great. It's not merely a matter of satisfied curiosity, it can also produce startling encounters with lives long past, the satisfaction of detective work -- and even a strong new sense of your own identity.

Not surprisingly, many of those drawn to genealogy in Japan are older people with time to spare. Among them is 81-year-old Takashi Sagara, a retired carpenter who lives in suburban Tokyo. For him, the dream of compiling his family tree began in childhood, but it wasn't until about 20 years ago that he finally got down to it.

As a child growing up in Osaka, Sagara's fascination with his family roots was inspired by his father, Minosuke, a paper cutter who was also a rakugo comedian who often sat him on his knee and told him tales about his grandfather, Kurataro, a samurai who served the Hosokawa domain in present-day Kumamoto Prefecture in Kyushu.

But they had a problem: The proud family had lost track of where Kurataro's ancestors were from.

"My grandfather apparently didn't talk much about his family, probably because he broke a samurai taboo," Sagara says.

What he did talk about, though, was the stuff of romantic fiction. It seems Kurataro was working at daimyo Hosokawa's Osaka residence when he fell in love with a maid there named Toku. Such free relationships were frowned on in those days, Sagara said, and Kurataro had to choose between his patrimony and love. The samurai followed his heart -- and lost his job and warrior status.

Thereafter, Kurataro raised his family in Osaka until he passed away in his 40s, never having returned to Kumamoto. Sagara's relatives vaguely knew their background, he says, but none before him attempted to trace it. "I felt that if I didn't do it, we would really lose our roots," he explains.

But Sagara, who became a carpenter at age 15, had to nurture his dream for decades. After the war he moved to Tokyo and set up his own construction firm. Though preoccupied with his work and raising a family, Sagara says that since he was 18 he had gradually been gathering documents and details of surnames, crests and local history.

Then, when he finally began tracing his ancestors when he was in his 60s, Sagara says that he was shocked that all the 50 written inquiries he sent to temples in Kumamoto drew a blank. In fact it wasn't until he joined some genealogy societies that things looked up, when another member found he had an old document that included the names of some of Sagara's ancestral family members.

Armed with this new lead, Sagara then went to Kumamoto and sought out archives containing the names of samurai who served the Hosokawa domain -- including some with the same surname. From this source, he traced another branch of Kurataro's descendants living in Nagasaki Prefecture. From them, Sagara was finally able to learn at which temple in Kumamoto his ancestors were buried.

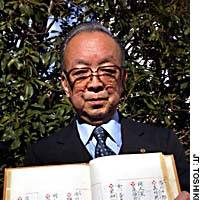

In addition, they later sent him a copy of a family record from around 1680 that enabled Sagara to track down 11 generations before him. Today, he continues his research to trace his even more distant ancestors, saying with enthusiasm: "I want to complete it before I turn 90."

Oral history handed down through his family was also the spark that inspired 74-year-old Koshu Ichikawa's quest to trace his family tree.

For Ichikawa, who lives in Chiba Prefecture, the stories came from his mother, who died at the age of 40. "As my mother was dying, she said, 'Let the world know more about the scholars among our ancestors because their achievements should be recognized,' " Ichikawa recalls from a conversation back when he was 18.

Among details his mother passed on were that these scholars included an 18th-century Confucian named Ichikawa Kakumei, his son Ichigaku, an engineer involved in the construction of Matsumae Castle in Hokkaido, and his son Jyuro -- Ichikawa's great grandfather -- who explored Hokkaido in the 19th century by order of the shogunate. All these, apparently, served the Takasaki domain in present-day Gunma Prefecture.

As in the case of Sagara, though, it was a while before Ichikawa, who worked as a lyricist at a record company, had any opportunity to build on these fascinating family foundations.

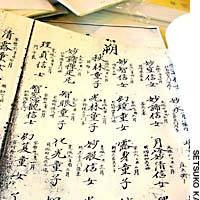

Once he began tracing his maternal ancestors, though, Ichikawa soon became absorbed in his research. He had a stroke of luck when a descendant of Ichigaku's disciple helped him obtain a copy of a late-19th-century family registry from the Meiji Era (1868-1912). Called jinshin koseki, such documents -- which contain wide-ranging and detailed information on people, including occupation, class, medical history and any criminal record -- are now deemed too sensitive to be released. (Since 1968, jinshin koseki have been unavailable to the public.)

Ichikawa's journey back to his ancestors led to him discovering several other key pieces of information along the way -- including a family document in Hokkaido, where both Ichigaku and Jyuro had connections.

Eventually, though, his research led him to a family in Saitama, and further investigation revealed that this was the Ichikawa honke, or main family, from which his own bunke (branch family) had split off 300 years before.

Not only that, but this main family had lived in the same locality for 800 years.

Until Ichikawa's discovery, neither side had known about the existence of the other. Now they keep in close contact. "I was really happy at the reunion," Ichikawa says. "Things like this are part of the attraction of making family trees."

Sagara and Ichikawa have successfully traced their roots back more than 300 years, partly because they were fortunate to have had vital information passed on to them through their families and were able to trace key documents.

That done, however, collating information can take time. Premodern handwriting is hard to decipher, and the details contained in early documentation is not always accurate.

Old family trees are no exception. According to lawyer Toshio Hoga, 57 -- whose consuming interest has long been researching pre-existing family trees back beyond the 1603 foundation of the shogunate to ancient times -- more than 90 percent of such lineages contain mistakes.

Not all errors were accidental. In premodern eras, Hoga explains, family trees were partly used to judge who would inherit property or hereditary ranks -- hence providing ample motives for forgery.

Similarly, during the Edo Period (1603-1867), a family tree was, especially in the samurai class, often used as a resume when applying to serve a lord of a domain. This, too, was a good reason for many to tweak their genealogy.

"Although these problems exist," Hoga says, "they don't invalidate the entire thing. What's important is to examine the family tree thoroughly by comparing different documents, and then assess which parts are accurate. It's almost like reading mysteries."

Despite the effort required, Ichikawa says, the process of tracing ancestors is fascinating. In fact, utilizing the knowledge and skills he gained from his own experience, 29 years ago Ichikawa started a business that undertakes investigation of people's genealogy on request.

So far, Ichikawa has worked for more than 600 families, and has traveled to all Japan's prefectures except Okinawa in the course of his investigations. For each project, however, he receives just 400,000 yen, no matter the number of trips he makes to conduct research or visit graves and even households. The entire process usually takes about four months, he says.

Ichikawa says he makes it a rule to follow a family's lineage back as far as he can -- as long as he is sure of the accuracy of the evidence he uncovers.

Sometimes, though, he says he encounters clients who would like him to tamper with the evidence, usually to connect them to historical figures. Ichikawa strictly refuses all such requests. "It's meaningless to fake ancestors or compile a family tree without any proof that what's written is right," he declares firmly. "I would never do anything like that -- it would insult my own ancestors."

While Sagara and Ichikawa dreamed of compiling their family trees from their youth, Ichikawa explains that many of his clients -- who include doctors, company presidents and Diet members -- are motivated by their own success in business. "They come to me saying they want to compile their family trees and leave their achievement for their descendants to know about."

That compiling a family tree should appeal to life's winners comes as no surprise to Kazuo Seiyama, a professor of sociology at the University of Tokyo. "For these people, it probably stems from a desire to find a family foundation for their own success," he says. "They want evidence that it was not just luck or coincidence."

Younger people, Seiyama adds, are still busy building up their achievements and tend not to feel the same need to forge links to their ancestors. Sagara is living proof of this -- lamenting that none of his six children or eight grandchildren are interested in tracing their roots. "That's why I feel an added responsibility toward my descendants," he says. "And I believe a lot of elderly people like myself feel the same."

Another factor behind younger people's indifference to tracing their family trees may be that, until World War II, the prime concern of a family was to ensure that its business or properties were passed on intact. Adoption was a common practice to maintain a family line.

However, with so many Japanese now salaried employees who are not involved in family businesses, the idea of family continuity has diminished in importance. "To many people today, their own success may be important, but that doesn't link to the success of the family anymore," Seiyama says.

He also noted that making family trees may hold less appeal for women than men, as Japan is a patrilineal society.

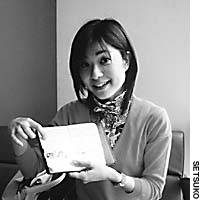

Unusual on both counts, then, is Satsuki Sugimoto, a 29-year-old company employee in Tokyo. Two years ago, Sugimoto's parents in Hyogo Prefecture happened to obtain five generations of the family's records from the family temple at a memorial service.

Having been born to a 58-year-old father who was the youngest of 10 siblings, all Sugimoto had known of her ancestors till then were the names of her grandparents, who had all passed away.

The family tree, though, opened the window on her past much wider -- back as far as an ancestor who died in 1860. Excitedly, Sugimoto copied the family tree into her address book, which she now has with her wherever she goes.

"I used to think of my ancestors collectively as 'ancestors,' but now that I know their names individually, I feel closer to them," she says.

From the family tree, Sugimoto also learned that her grandfather was adopted to succeed the headship of the Sugimotos, and that several of her aunts and uncles had died in infancy or when they were very young.

"You tend to believe that you are an isolated individual, but there are so many people connected to you," Sugimoto says as she looks at the family tree. "And whether good or bad, my ancestors lived their time and it's because of them that I'm here."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.