Sitting on top of four major tectonic plates, Japan is one of the countries most at risk of earthquakes.

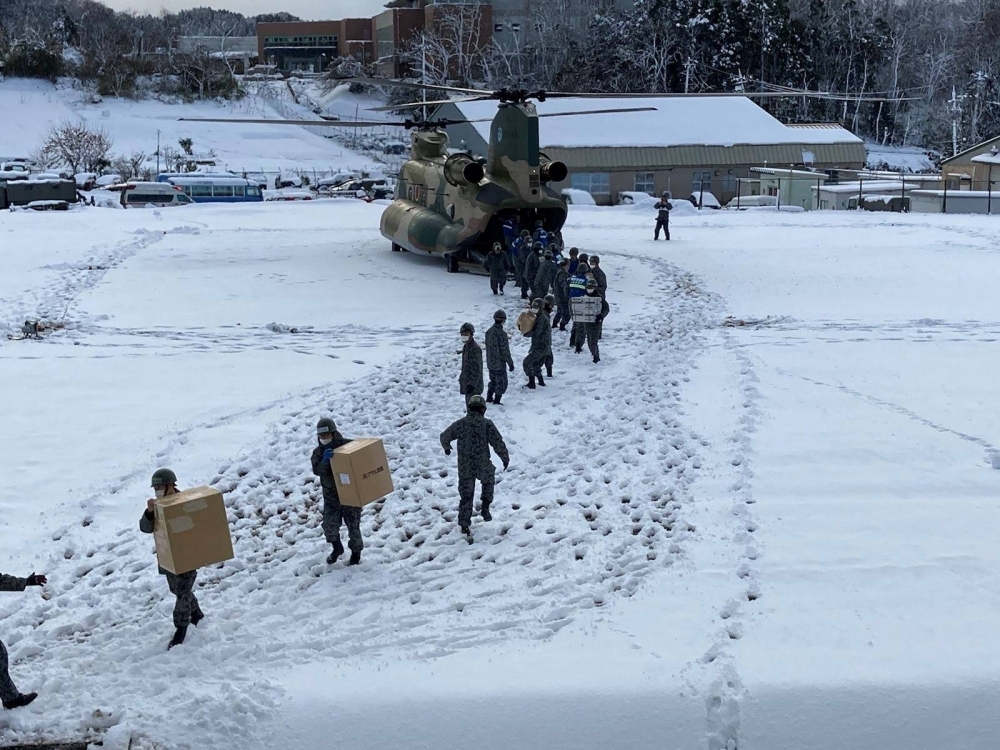

That fact was demonstrated in tragic and dramatic fashion on Jan. 1, when a magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture, directly and indirectly killing as many as 275 people, knocking out key infrastructure, displacing thousands and severely damaging or destroying tens of thousands of homes.

The Noto Peninsula has, in fact, been experiencing an ongoing “seismic swarm” — many earthquakes within a relatively small area that don’t fit a “mainshock-aftershock” pattern — since late 2020, with this generating earthquakes at 10 times the average regional rate. No one knew why — but now a major clue has emerged.

A new study by Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientists shows that heavy snowfall and rain can influence how and when earthquakes happen. When looking for the cause of an earthquake, the search is typically internal, beginning underground. But the study, published May 8 in Science Advances, shows that earthquakes can have external, aboveground triggers as well.

The scientists analyzed a series of earthquakes in the Noto region that occurred between 2012 and 2023, finding that the seismic activity in the region is synchronized with changes in underground pressure, which is influenced by seasonal patterns of precipitation. According to them, heavy snowfall has more of an influence than heavy rain.

For Qingyu Wang, lead author and seismologist, it is important to analyze the interaction between the internal and external processes.

“Currently, most people either only look into environmental effects (like weather) or ... the internal process, like long-term tectonic forces. For me, I’m really interested in combining both the internal and external,” she says.

The climate crisis also has an influence. “Sea level changes in the Sea of Japan play a role,” Wang says, with the sea level increasing by about 1 meter during the summer and winter.

And the effect from climate change could become more pronounced, the researchers predict.

“If we’re going into a climate that’s changing with more extreme precipitation events, and we expect a redistribution of water in the atmosphere, oceans, and continents, that will change how the Earth’s crust is loaded,” William Frank, one of the study’s authors and an assistant professor at MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, said in a news release.

Still, Wang stresses that heavy precipitation itself is not the direct cause of earthquakes. The main trigger is sudden movements along faults on tectonic plates — Japan currently has over 2,000 active faults. However, this trigger alone was not enough to explain why the Noto Peninsula has been experiencing so many earthquakes.

Water-clogged

Inland earthquakes in Japan predominantly take place at relatively shallow depths of 10 kilometers or less. The earthquakes on the Noto Peninsula began at a depth of about 15 km, which suggested that there was an underlying force. And the distinct way in which these earthquakes migrated upwards and decreased in velocity suggested that this underlying force was the presence of deep fluids, which stemmed from precipitation.

"The earthquake swarm is then caused by deep fluid migration that is triggered by intense seasonal changes in excess pore pressure caused by intense seasonal precipitation,” Wang says.

Similar to how the pores on our face are tiny openings that can get clogged with oil and sweat from our glands, the pores in the Earth's crust on the Noto Peninsula got clogged with water from seasonal patterns of snow and rain. When these pores in Noto got clogged, it slowed down the velocity of seismic waves, thereby shifting the deep fluids toward the shallow preexisting fault zones, where the earthquake swarm occurred.

Japanese scientists had previously proposed that a build up of water might be behind the seismic swarm.

Although this study only looked at earthquakes in Japan, the researchers note that heavy precipitation could play a role in earthquakes elsewhere, too.

The New Year’s Day earthquake, meanwhile, occurred within the same swarm source that Wang’s study analyzed. But without further research, the MIT scientists say that it is unclear whether heavy precipitation played a role or not.

“Once there will be more high-resolution spatial temporal analysis (of the New Year earthquake), there will be a more precise conclusion on the potential link between (it) and the earthquake swarm,” Wang says.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.