It’s November 2020, and despite the ongoing pandemic, groups of enthusiastic amateur researchers are making their way through the National Museum of Nature and Science’s Tsukuba Research Departments as part of its annual opening to the public.

The event is a rare chance for people to take a tour of the sprawling Ibaraki Prefecture facility, which stores 99% of all specimens belonging to the museum.

Among the eager attendees are Hinako Komori, a 10-year-old elementary school student, and her father, Hidemi. Hinako has been an avid animal lover since she was 3, with a special interest in extinct species — particularly the Japanese wolf, an apex predator that disappeared over a century ago.

The first stop on the guided tour is a building where the museum preserves over 2 million specimens from the animal, plant, geology and human research departments.

As they work their way through the seventh floor dedicated to taxidermies of terrestrial mammals, Hinako notices a mounted canid specimen sitting on the very bottom of a shelf, half hidden in the shadows. It’s rather small, and she sees it has a bushy tail as well as a short neck and front legs. It also lacks a stop, or the bulging frontal furrow found in dogs.

She pauses. Hinako had spent hours pouring over photographs of Japanese wolf specimens, and she thinks this particular taxidermy resembles the one preserved at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands — one of only four stuffed specimens of the beast left in the world.

She points at it, and whispers to her father: “Papa, it’s a wolf. A Japanese wolf.”

Excitedly, she approaches the researcher guiding the tour and asks whether the specimen is the wolf.

“I wonder what it is, I don’t know,” he says, and continues on with the tour.

That chance discovery over three years ago triggered an investigation into the origins of these particular remains, led by Hinako and two academics: Sayaka Kobayashi, a researcher at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, and Shin-ichiro Kawada, a researcher at the National Museum of Nature and Science’s Department of Zoology.

Their findings were published Thursday in the Bulletin of the National Museum of Nature and Science, a quarterly journal, under the title: “Is A Skin Specimen of ‘Yamainu’ in the Collection of the National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo, a Japanese Wolf Canis lupus hodophilax?”

The answer? Extensive research based on surviving records indicates that the specimen Hinako saw, labeled M831, could be one of two Japanese wolves kept at Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo in the late 19th century — a rare discovery that may shed new light on the mysterious carnivore.

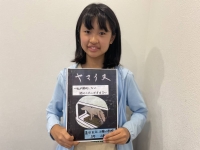

“When I came across that stuffed animal, I instantly fell into a state of excitement because it matched my image of a Japanese wolf,” says Hinako, who is now 13 and attending junior high school.

“If I didn't know the characteristics of the Japanese wolf based on its appearance, I wouldn’t have noticed it.”

Japan’s lost wolves

The Japanese wolf once roamed the forests and mountains of the islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, but it is thought to have died off as the nation marched toward industrialization in the 19th century.

Worshiped for centuries as a divine messenger for preying on crop raiders such as wild boar and deer, the animal was nevertheless exterminated by what is believed to be a combination of disease and humans hunting them in the name of protecting livestock.

The last known Japanese wolf was killed in 1905 by hunters in Washikaguchi, a remote logging village in Nara Prefecture, and purchased by American zoologist Malcolm Playfair Anderson. The animal’s skull and pelt are at the Natural History Museum in London.

Its tragic fate, however, along with the lingering mystery over its true nature and even reports of modern-day sightings, has kept the beast alive in the minds of many.

Today, specimens — and there are few — including skulls, fangs and pelts stored in museums and personal collections, as well as written records, illustrations, statues and other antiquities, are all that are available for researchers to paint a clearer picture of the creature.

Among them, the most prominent are the four mounted specimens.

One is in Leiden, with this particular animal obtained in Japan by German physician and botanist Phillip Franz von Siebold in 1826. It is considered a type specimen, or one originally used to name a species or subspecies.

Recent genetic analysis, however, has found that while it matched the Japanese wolf, its skull shape has obvious inconsistencies to other Japanese wolf specimens. This has led researchers to theorize that it may represent a wolf-dog hybrid of a Japanese wolf mother and dog father.

The other three stuffed specimens are in Japan. One is exhibited at the National Museum of Nature and Science in the Ueno district of the capital, while the other two are stored at the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Agriculture and Wakayama University’s Faculty of Education.

The specimens indicate the beast was much smaller than its continental counterparts for reasons that are not entirely clear, though some experts suggest the phenomenon of “island dwarfism” may be behind this. Recent DNA research, in the meantime, points to its ancient origins and the possibility that it was the closest relative to the ancestors of dogs, more so than any other gray wolf population.

Hinako has devoured the literature on the animal and kept herself up to date on recent scientific discoveries. And living in Tokyo, she is quite familiar with the taxidermy displayed in Ueno through frequent visits to the museum, giving her a keen eye for detail when it comes to her favorite animal.

“I first encountered the Japanese wolf when I was 3 years old and saw a stuffed wolf at the National Museum of Nature and Science,” she recounts.

“In researching the Japanese wolf, I found that each taxidermy of the Japanese wolf is different, and that there are many questions that remain unanswered. ... The variety of opinions on the Japanese wolf deepened the mystery, expanded my imagination, and made me want to someday find out what they really are.”

Probing for answers

The day after she returned from the tour of the Tsukuba research facility, Hinako sent a message to the National Museum of Nature and Science inquiring about the identity of the mysterious taxidermy she saw.

Three months later, she received a response. It said the specimen was labeled M831 and is believed to be a type of yamainu (mountain dog), and may have been one of the first animals kept at Ueno Zoo. Hinako was elated, as “yamainu” was often used to refer to the Japanese wolf until the early 20th century.

Using that information as a starting point, Hinako began delving into the literature from both contemporary Japanese wolf researchers and those of the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

She discovered that, in 1888, Ueno Zoo apparently took possession of two wolf pups from Iwate Prefecture that had been acquired by the Tokyo Education Museum (now the National Museum of Nature and Science).

She then rummaged through animal records stored at the Imperial Museum in Tokyo (now the Tokyo National Museum) and interviewed the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology’s Kobayashi about the specimen registry at the Imperial Household Museum (another previous name for the Tokyo National Museum). Through her research, Hinako became convinced that M831 was, in fact, one of the two Japanese wolves Ueno Zoo had kept.

In August 2021, she compiled her findings into a hand-written report and submitted it to a research competition for upper elementary school students. Her report won an education ministry award the following January.

A ‘great talent’

Meanwhile, Kobayashi, who read Hinako’s report, and Kawada, who offered Hinako advice along the way, suggested that the three work on turning her discoveries into a scientific article.

“To be able to pick out from a room full of specimens one that appeared like a Japanese wolf, I think she has great talent for noticing things,” Kobayashi says.

Hinako says that before starting to write the paper, Kobayashi offered some important advice.

“Science requires objectivity,” Kobayashi told her. “Keep your passion in mind, but keep your writing calm.”

In the paper released Thursday, the authors say they found that the stuffed specimen had not only the M831 label but also another, partially torn, specimen number sticker on its base that could either be read as 38 or 88. Past records of M831 also indicated that the specimen had been disposed of, suggesting significant confusion in its taxonomic past.

To unravel the mystery, the authors examined the external morphology of M831, traced the history of specimens belonging to the genus Canis that were part of the Imperial Household Museum collection and studied the breeding records of animals belonging to that genus in the Ueno Zoo.

“We confirmed,” the paper says, that “this specimen M831 was considered to be one of two wolves that arrived at Ueno Zoo from Iwate Prefecture, Japan, in 1888. Therefore, it is thought that this specimen is a Japanese wolf.”

Kawada worked on comparing the morphological characteristics of M831 to other Japanese wolf specimens and reached the conclusion that measurements and other features of M831 were such that it could be considered the real deal.

The specimen lacks a skull, however, and its posture and appearance could be based on the subjective judgment of whoever created it.

And while DNA analysis would be necessary to reach a definite conclusion, Kawada says there are no immediate plans to conduct genomic research, since such tests often damage specimens.

“Technology is advancing rapidly. Perhaps by the time Hinako attends college or graduate school, there will be a better foundation to produce results with more accuracy,” he says.

“Until then, we will be preserving this rare specimen.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.