In the summer of 1689, the poet Matsuo Basho left the port town of Sakata in Yamagata Prefecture and traveled north along the Sea of Japan. His destination: Kisakata, an inlet dotted with 100 or so small, pine-covered islands that had been a well-known natural attraction since the Heian Period (794-1185).

It was also the northernmost stop during the legendary haiku master’s 160-day journey on foot in the Tohoku region that led to his seminal work, “Oku no Hosomichi,” a poetic diary known in English as “The Narrow Road to the Deep North,” considered one of the literary masterpieces of the Edo Period (1603-1868).

After admiring the majestic lagoon, Basho composed the following haiku, likening the flowers of the nebu (mimosa tree) to the elegance of a sleeping Seishi, or Xi Shi, one of the Four Beauties of ancient China:

Kisakata ya (Kisakata —)

ame ni Seishi ga (Seishi sleeping in the rain)

nebu no hana (Wet mimosa blossoms)

Today, the creations of the celebrated poet and others are all that remain of the once famous ocean cove.

“That scenery Basho praised disappeared after a magnitude 7.1 earthquake struck the region on July 10, 1804,” says Kazuki Saito, a local historian and official at the cultural properties protection division of Nikaho, the city in Akita Prefecture that’s home to Kisakata.

“The seismic upheaval saw the seabed rise, and the ‘islands’ are now surrounded by land, not water,” he says. “It’s quite similar to what happened in Noto.”

Saito is referring to how a 7.6 magnitude temblor that rocked Ishikawa Prefecture’s Noto Peninsula on New Year’s Day saw the ground rise up to 4 meters in some areas along its scenic coast, devastating the region’s fishing industry and exposing shells, starfish and other shallow-water marine fauna and flora.

The calamity was also a reminder of how Japan, located on the volatile “Ring of Fire” and wedged among four major tectonic plates, has been shaped by rumbling, grinding and often deadly convulsions and volcanic activity.

Ever since breaking off from the Eurasian continent 20 million years ago and opening the Sea of Japan, the archipelago has always been at the mercy of nature’s seismic whims, its landscape and ecology undergoing perpetual transfiguration.

That unpredictability and lack of control over the environment helped brew a unique Japanese sense of embracing transience and impermanence.

During his trek up north, Basho is said to have discovered the philosophy of fueki ryūkō, or the unchanging and the ever-changing, a concept encapsulating the continuous transformation of nature through time and its seasons.

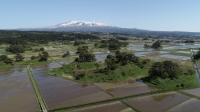

“The islands of Kisakata are now more like mounds surrounded by rice paddies,” Saito says.

“But during April and May when the fields are filled with water in preparation for planting rice, a view reminiscent of the old Kisakata is resurrected.”

Unprecedented uplift

The earthquake that struck off Noto Peninsula’s northern coast at 4:10 p.m. on Jan. 1 pulverized homes and buildings, ignited firestorms and triggered landslides and tsunamis. Altogether, the disaster had claimed the lives of 238 people as of Feb. 1.

While nature’s wrath was ravaging the landscape, another phenomenon was rapidly manifesting itself below the feet of panicked residents: massive ground displacement of a scale unseen in the past century.

“The widespread uplifting likely took place in the short period during the violent shake,” says Tatsuto Aoki, an associate professor at Kanazawa University who has been conducting fieldwork in affected areas.

“It must have been a peculiar scene for those present, watching the ocean recede before their eyes and unaware that the ground they were standing on was swelling up.”

According to an analysis by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan using data from the Advanced Land Observing Satellite-2, also known as Daichi-2, an uplift of over 1 meter was observed across a wide swath of northern Noto, while sections of the western portion of the city of Wajima were elevated by as much a 4 meters.

Meanwhile, a report released by the Association of Japanese Geographers estimates that the quake pushed up land along 90 kilometers of the peninsula’s coastline, thrusting the seaboard outward by about 240 meters in Wajima’s district of Monzenmachi Kuroshimamachi.

Aoki, an expert on physical geography and regional disaster prevention, has been navigating the hazardous roads up to the peninsula from Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa, to record the impact of the quake.

“In a word, I’m shocked,” he says. “The scientist side of me is overwhelmed by the immensity of the natural phenomenon, while as a local resident, the dramatic change in scenery is heartbreaking. I’m still not able to process these emotions.”

Aoki says ground displacement of similar scale — or perhaps even larger — was detected during the 1999 Jiji Earthquake that slammed Taiwan. In Japan, however, an upheaval of this magnitude has not been seen “for at least 100 years,” he says.

“There will be a long-lasting impact on local fisheries, communities and the environment,” he continues.

“While Noto may appear remote and secluded, it has a vibrant history and its residents have lived on their land for hundreds of years, relying on its plentiful seafood not only for their living, but also as an important communication tool,” Aoki says, describing how people living on the coast would build relationships with those living inland through the exchange of fish for farm produce.

Ishikawa Prefecture was ranked 16th in the nation in terms of the volume of its catches in 2020; hauls are concentrated on the peninsula, known for its abundant fish reefs. According to a prefectural survey, however, damage to breakwaters, wharves and waterfront roads were recorded in 60 of the 69 fishing ports in Ishikawa after the quake.

While reconstruction work has begun in many harbors, the region is aging rapidly, raising concerns over the dwindling number of fishers. According to a national census from 2020, 43.4% of residents of the Noto Peninsula were 65 or older, far higher than the national average of 29.1%.

Meanwhile, scientists will be studying the ramifications of the changes to the region’s geography and topography for years to come.

“When the ground lifts, the flow of rivers, streams and groundwater shifts over a five- or 10 year-period, as well as the coastline and even inland terrain,” says Aoki. “That also has a direct impact on organisms living in the ocean and rivers of affected zones.

“There’s no doubt Noto will offer a vast opportunity for research to understand the dynamism of nature.”

On shaky ground

Japan is the most seismically active country on earth.

It’s home to around 10% of the world’s active volcanoes, and 18.5% of all the earthquakes across the globe happen here. In 2021 alone, Japan recorded over 2,400 temblors that registered at least a 1 on the nation’s shindo seismic intensity scale, which goes up to 7.

The island chain was part of the Eurasian continent until around 23 million years ago before subducting plates pulled the archipelago eastward, separating it from the continent and creating the Sea of Japan. Over millions of years and glacial and interglacial periods, these islands gradually assumed their present state and shape. Today, Japan lies in a particularly volatile area at the boundaries of four tectonic plates: the Pacific, Philippine Sea, North America and Eurasia.

“The Japanese archipelago was created by active uplift and subsidence and repeated earthquakes such as the recent one that befell Noto,” says Hideaki Goto, an associate professor at Hiroshima University who led the Association of Japanese Geographers’ survey of crustal movements following the disaster.

Goto estimates the Noto Peninsula expanded by about 4.4 square kilometers as a result of the earthquake, which also may have caused the ground to tilt, lifting the northern portion of the peninsula while lowering certain areas in the south.

“From a broader perspective, similar quakes, uplifting and sinking of the land have been occurring on the peninsula over a period of 120,000 to 130,000 years, resulting in the formation of its current hills and terraces.”

During a symposium hosted by Tohoku University last month, Shinji Toda, a seismologist at the educational institution, said a group of active faults beneath the peninsula and the sea formed a band stretching 100 km, causing the immense jolt.

And considering the peninsula’s geological features, he estimated that seismic energy capable of causing ground uplift of this scale had built up over 3,000 to 4,000 years.

Goto explains that while the recent disaster stood out for the extent of ground displacement, evidence of similar seismic episodes can be observed in many locations throughout Japan, including those from the Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo a century ago.

Around noon on Sept. 1, 1923, a convulsion estimated at a magnitude of 7.9 struck off the southern coast of Kanagawa Prefecture, rocking the capital, the neighboring city of Yokohama and beyond. The violent shakes and the raging infernos that ensued claimed the lives of 105,385 people, making it the deadliest earthquake in Japan’s recorded history.

“Traces of how the quake elevated land can be seen, for example, toward the southern end of the Miura Peninsula (in Kanagawa),” Goto says. “The area shares similar characteristics to the Noto Peninsula.”

Tectonic testaments

On a clear day, views of Mount Fuji, Oshima island and the Boso Peninsula can be observed from Jogashima, a small island off the southern tip of the Miura Peninsula, around 70 kilometers from Tokyo.

A tourism destination for centuries, the island, jutting out into the Pacific Ocean, is also known for inspiring the works of famed poet Hakushu Kitahara, memorialized in the lyrics he composed for the song “Jogashima no Ame” (“Jogashima in the Rain”).

Meanwhile, traces of ground uplift from major earthquakes of the past, including the 1703 Genroku Earthquake, are etched on the rocky beach and terraces that occupy the southern coast of the island.

A postcard from 1918, for example, shows how a natural rock-arch known as the Umanose Domon (roughly, Horseback Cave) used to be half submerged under the ocean before the seabed was lifted by approximately 1.5 meters during the 1923 Kanto earthquake.

In fact, the quake made the port of Misaki temporarily rise about 6 meters, making it possible to walk across to Jogashima for several days before the sea level gradually returned due to subsidence caused by the aftereffects of the convulsion.

“The Miura Peninsula is home to many coastal terraces formed from seismic activity,” says Saeko Ishihama, a researcher at the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Natural History.

“Among the oldest are the remains of the seafloor from around 120,000 years ago found on a mound around 100 meters above sea level.”

In “Japan Sinks,” the 1973 best-selling sci-fi novel by the late author Sakyo Komatsu that spawned a 2021 series that aired on TBS and Netflix, the Japanese archipelago is consumed by the sea following a series of catastrophic earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis.

While the two-volume epic highlighted the geological risks facing the quake-prone nation, ground displacement triggered by large temblors, as well as landfill projects and volcanic bursts have seen Japan’s total land mass actually grow, albeit bit by bit.

Ishihama says the coastal uplift of land seen following the Noto quake, as well as those recorded in the past in the Miura Peninsula and elsewhere, offers a window into how the island chain was molded over millions of years through seismic and volcanic activities.

“Without the powerful forces that create earthquakes,” she says, “Japan wouldn’t exist.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.