In spring 2021, under the low ceiling of the Sompo Museum of Art lobby in Shinjuku, masked visitors trickled through rows of retractable belt barriers en route to works by Piet Mondrian. Up a few floors, they moved through the galleries leisurely, lingering before the Dutch painter’s instantly recognizable squares of red, yellow, white and black, then moving on.

Two and a half years later, these same galleries contain a very different energy. “Van Gogh and Still Life,” on now at Sompo until Jan. 21, is stuffed to the gills with museum-goers. In front of the centerpiece of the show, one of Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” runs a steady stream about six people deep, their phones and cameras held at the ready. Behind them, a line snakes through the whole of the gallery.

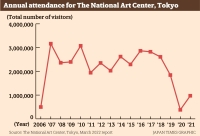

After three years of museum closures, exhibition postponements and border closings, 2023 marked a return for Tokyo’s biggest art museums. This year saw a lineup of blockbuster exhibitions, including a number of modernist paintings on loan from Europe and, with them, crowds of eager art-goers.

This year, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo saw some of its highest attendance figures of the past decade, its press department says. A David Hockney exhibit, on from July 15 to Nov. 5, had just under 230,000 visitors (about 2,400 a day on average) — the museum’s largest solo exhibition of a contemporary artist to date. The publicity department notes that inbound tourism from outside Japan, especially from the West and Asia, was a major factor in the exhibit’s popularity.

Visitors stood chin to shoulder trying to catch a close look at works like “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy,” a double portrait with feet buried memorably in a fur rug. By the final space, the gallery and crowds opened up, making room for “A Year in Normandie,” a 90-meter-long scroll constructed from one of Hockney’s iPad works that he drew during the start of the pandemic.

One of the city’s biggest exhibitions of the year was “Painting Love in the Louvre Collections,” at the National Art Center, Tokyo, which showed 16th to mid-19th century paintings curated from the collections of the Louvre in Paris. Around 450,000 visitors (about 5,100 a day on average) saw the show from March 1 to June 12.

At Ueno’s Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, “Henri Matisse: The Path to Color,” ran across the record-breaking heat of summer, from April 27 until Aug. 20. About 440,000 visitors total (about 4,400 a day on average) went to see works by the Fauvist French painter, which included “Luxe, Calme et Volupte” and “Odalisque with Red Trousers.”

The museum’s gift shop was an impressive spectacle unto itself. Wading through the dense throng earlier this year, I could viscerally feel that the art crowds were back in Tokyo — and they’d brought their wallets. Across the park a few months later, that proved true again when a Claude Monet show opened at the Ueno Royal Museum: The gift shop has its own separate ticketed entrance, the line marked off by signage, barriers and traffic cones.

These are not quite pre-COVID numbers, however. For one thing, at Tokyo’s large art institutions, the pandemic ushered in reservation and limited ticket systems that still remain in place, so it’s not fair to do a straight comparison to attendance numbers from before 2020.

As a press representative from the National Museum of Western Art notes in an email: “I have the impression that the number of visitors has decreased compared to before COVID, but both domestic and inbound foreign tourists have been increasing, and I have a sense that the number of visitors is gradually returning.”

The museum’s “Brittany, Land of Inspiration” had just over 163,000 visitors (about 2,200 a day on average) between March 18 and June 11.

But if attendance never returns to pre-COVID days, you’ll hear no complaints from me.

In 2019, the Gustav Klimt show at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum had a staggering 7,900 visitors a day, according to art news site Art Annual Online. The same year at the Ueno Royal Museum, the Johannes Vermeer exhibit saw an average of about 5,600 visitors a day in Tokyo and just under 6,700 when it moved to the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, according to contemporary art magazine Bijutsutecho.

Colleagues who attended those shows describe feeling like they were on a conveyor belt of spectators, in essence standing in one continuous line as they were shuffled past the works.

Judging by weekday crowds over the past year, the museum visitor caps should stay where they are or even be lowered. The exhibits that allowed photography were especially congested, and the insistent sound of faux camera shutters from smartphones added to the feeling of being in a zoo. At the Van Gogh show, docents hovered to police the photos, making sure no humans appeared in the images, and when I got to the final piece, a small part of me was relieved that the whole ordeal was over.

Which was a shame. Outside the bottleneck caused by “Irises” and “Sunflower,” there was so much pleasure to be found in the smaller moments: “Carafe and Dish with Citrus Fruit,” its mysterious lines inspired by Japanese woodcuts, and “Smoked Herrings,” both earthy and shimmering. It was amusing to learn that Van Gogh had wanted to draw figures but was too broke — after giving away much of his money — to afford human models, so he ended up painting cheaper subjects: flowers, landscapes and, of course, himself.

Some exhibits mostly banned photography — and benefited from it. The Yves Saint Laurent show at the National Art Center, Tokyo, with more generous ceilings and roomier galleries, gave a slight reprieve. It was possible to study the careful details of the French designer’s women’s tuxedo suits from 1970 and his excellent Babouchka wedding dress without worrying about blocking someone’s shot with the back of your head. More than 200,000 visitors attended the show, which ran Sept. 20 to Dec. 11.

But blanket restrictions on photography are not enough to manage the crowds everywhere. “Claude Monet: Journey to Series Paintings” runs until Jan. 28 at Ueno Royal Museum before it moves to Nakanoshima Museum of Art in Osaka in February. In its first six weeks, it had at least 200,000 visitors (about 4,400 a day on average).

The exhibit’s popularity is physically evident. On a recent Wednesday morning in the narrow galleries of the museum, visitors moved as a continuous pack about eight people deep, craning their necks to try and glimpse the sea at Varengeville as rendered by Monet. I had just a few seconds to be completely floored by each of the Impressionist’s “Haystacks,” grain captured in a dynamic exchange with light and weather, against the backdrop of a docent’s voice informing visitors it was not necessary to queue and that they could move freely.

Attendance is key to the longevity of these institutions, especially after an embattled few years; and until they look critically at the effect that stifling throngs have on the experience of the artworks, we viewers may just have to accept that the crowds are here to stay.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.