On the surface, the religious makeup of Japan is relatively simple. Buddhism and Shinto dominate; tiny communities of other faiths exist here and there. The reality is more complicated. For one thing, at least until the Meiji Restoration, the boundary between Buddhism and Shinto was, at best, blurry. In many locales, the two creeds merged into a syncretic cult, at times with shamanistic influences — think of Shugendo, with its mountain-worship and mummified monks.

In the late 18th century, a new type of divinity was added to the lot: Yonaoshi gods, “world-renewing” deities with the power to improve the material life of a community. The first person to achieve that status was Sano Masakoto (1757-84), a samurai who killed the scion of a corrupt and powerful Edo (now Tokyo) family. When the news broke, the city’s rabble was thrown into a tizzy, but even better tidings lay ahead: After Masakoto was forced by the authorities to disembowel himself, the price of rice almost immediately dropped. Few believed this was a mere coincidence and so Masakoto was declared a yonaoshi god for saving “the oppressed from their predicament.”

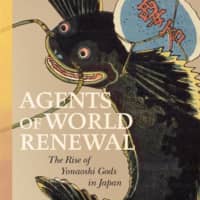

Yonaoshi gods — which are the focus of Takashi Miura’s slightly circuitous academic title, “Agents of World Renewal: The Rise of Yonaoshi Gods in Japan” — had neither permanent shrine nor ritual. Their cult, usually local, rarely lasted long and, at least until the late 1800s, none aimed at overthrowing the existing political order. What they offered, largely to the dispossessed, was “self-empowerment.” That, in a nutshell, is all most readers need to know about yonaoshi gods, but for the more curious sorts, or those with a keen interest in Japanese religion, Miura’s book awaits.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.