Tetsuyuki is nominally a university student in 1970s Osaka, though given his atrocious attendance record, this could hardly be classed as a campus novel. Any pretence at pursuing an education is abandoned when his father dies, saddling Tetsuyuki and his mother with a hefty debt. The yakuza are quickly called in to collect, prompting Tetsuyuki to run off.

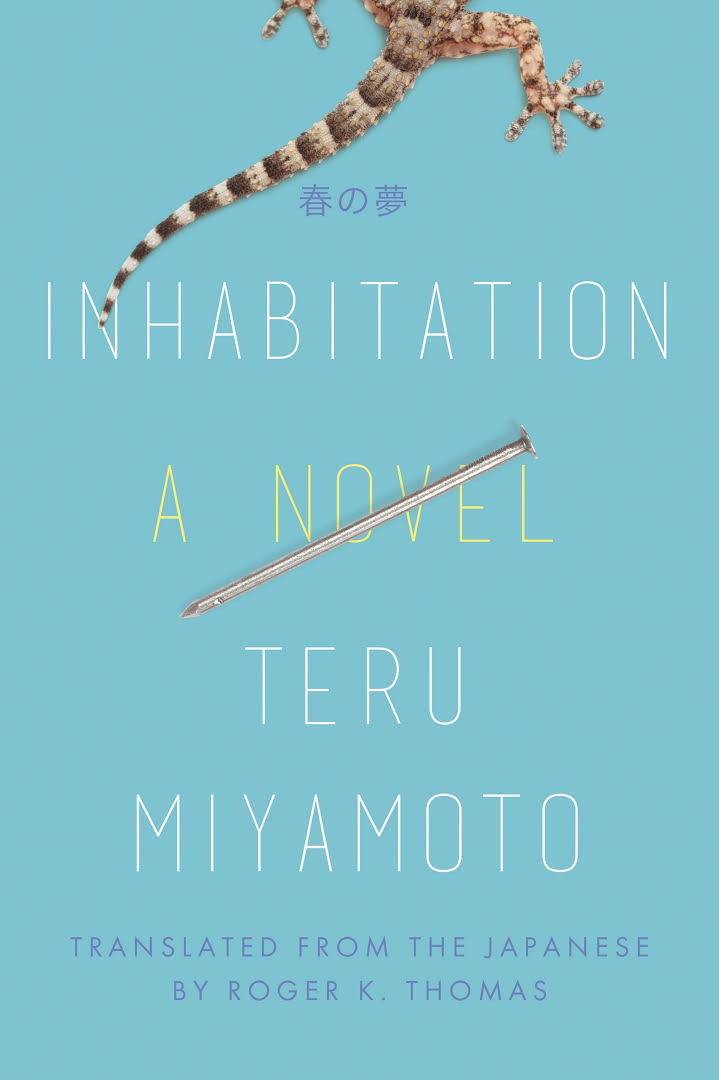

Inhabitation: A Novel, by Teru Miyamoto Translated by Roger K. Thomas.

320 pages

COUNTERPOINT PRESS, Fiction.

The novel begins on his first evening in his shabby apartment on the outskirts of the city. Attempting some basic DIY in the dark — the electricity has been disconnected — he accidentally nails a lizard to the wall. The lizard survives this onslaught, though only just.

Fans of symbolism will, of course, see the metaphor. Tetsuyuki is nailed down by his father's debt, his dysfunctional relationship with girlfriend Yoko and his lack of prospects. Dropping out of college forces him to work as a bellboy in a local hotel, yet even here any chance of advancement seems out of reach.

He keeps Kin — as he names the lizard — alive with food and water, and Kin's continuing survival seems to foreshadow Tetsuyuki's hopes of one day unpinning himself from his father's legacy: at least until the debt collectors find him.

Thomas' translation highlights the deep symbolism and existential dread of Miyamoto's novel without ever descending into the absurdist misery of true existentialist literature. While Tetsuyuki is far from a hero — he's so passive he couldn't even be called an antihero — our sympathy for his situation and the evident love he inspires in his mother and Yoko suggests that perhaps for Tetsuyuki — and Kin — not all hope is lost.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.