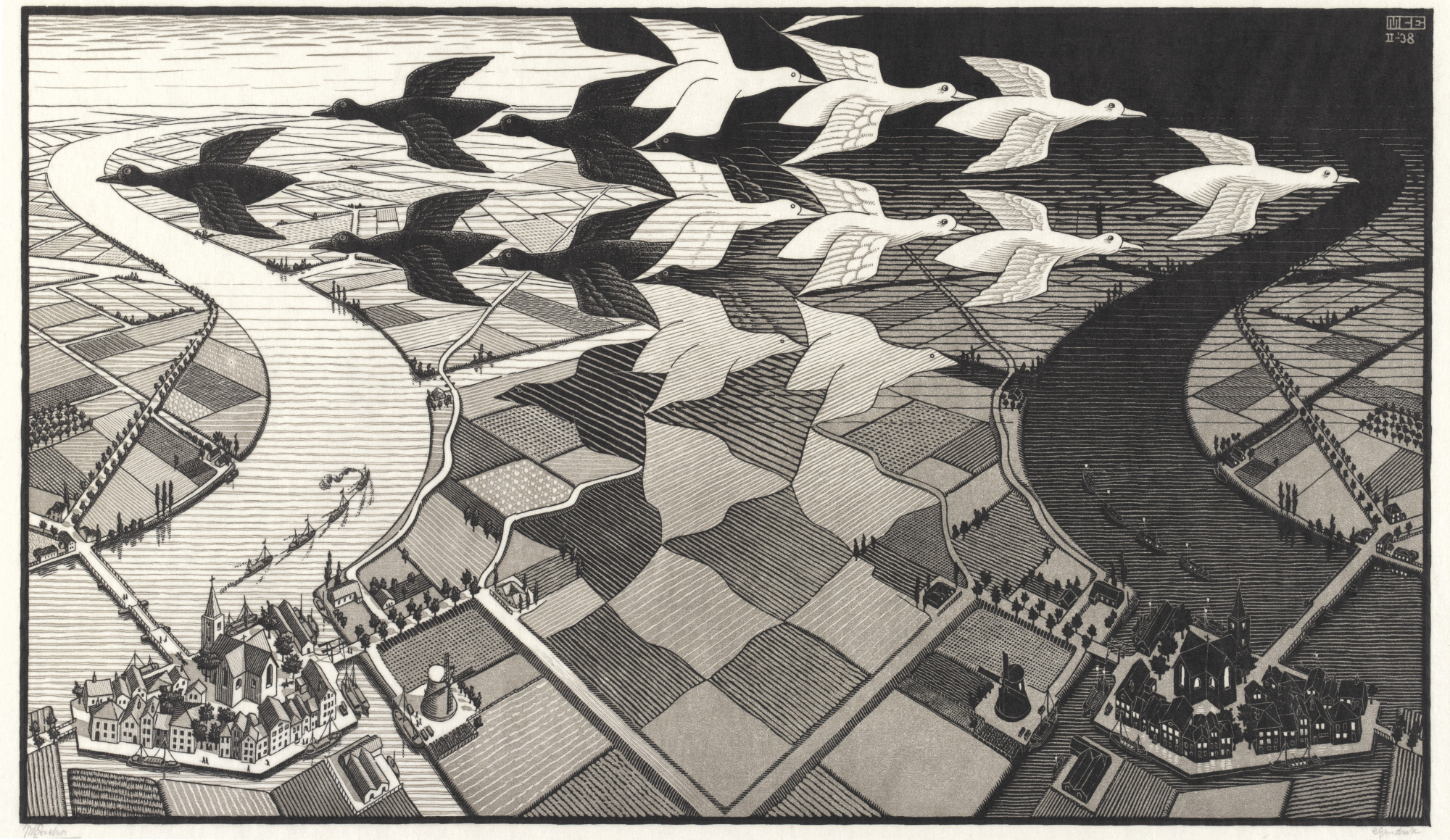

The Dutch printmaker Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher (1898-1972) followed in historical foundational art footsteps. His preoccupation with perspective was like that of the Renaissance; his self-portraits in convex mirrors remind us of Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441); the intricate stone topographies of his early oeuvre were in the vein of Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) and his mesmerizing architectures recall Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-78). Escher's audiences, however, were mostly from outside the art world.

"The Miracle of M.C. Escher: Prints from The Israel Museum, Jerusalem" at the Abeno Harukas Art Museum commemorates the 120th anniversary of the artist's birth with 152 works. A familial connection to Japan is that Escher's father, a hydraulic engineer, had worked in Osaka as well as in Mikuni and other areas of Fukui Prefecture between 1873 and 1878.

Escher's father wanted his son to be an architect, but Maurits was more interested in woodcut printing. Work from his younger years featured naturalistic representations of western Italian sceneries and townscapes, like "Castrovalva, Abruzzi" (1930), allegorical depictions of the world influenced by art nouveau and religious subjects. These themes, though, largely came to an end in 1935 after he copied Hieronymus Bosch's depiction of hell from the "Garden of Earthly Delights" (c. 1490-1500), partly in protest against the rise of fascism in Italy where he had been living.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.