There are two good reasons to see the exhibition on the short-lived photography magazine Koga, now on at the Tokyo Photographic Art (TOP) Museum. One is that it is full of powerful images that will linger in the memory despite their relative simplicity. The other is that, as the story of art continues to develop beyond the confines of paintings and sculptures by dead white men, the inventiveness and distinct character of the avant-garde photography in Koga deserves greater exposure for what it can tell us about Japanese visual culture of the 1930s.

Until the 1920s, fine art photography was dominated by the idea that in order to be taken seriously, it should be reminiscent of oil painting. Photography's ability to record the outside world with clarity and detail, the attributes that made it novel and unique, were considered too literal for a medium of artistic expression.

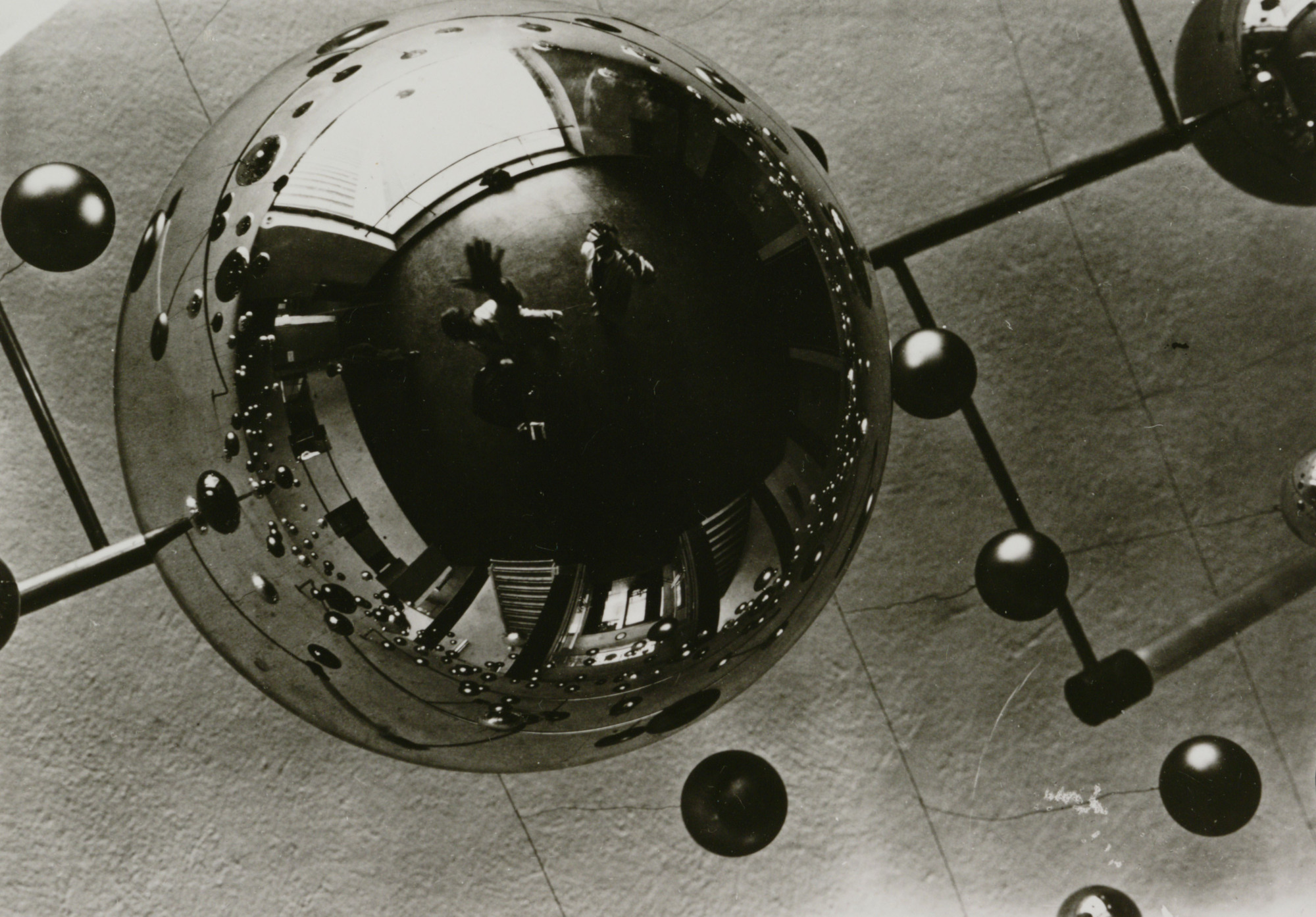

The German movements of the neue sachlichkeit (new objectivity), neues sehen (new vision), which arose in the mid- and late '20s respectively, both embraced the mechanical nature of photography and led to an ebullient outbreak of experimentation. Collage, photomontage, abstraction, solarization and generally making the everyday uncanny arose in a spirit of social criticism and desire to expand the limits of human perception.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.