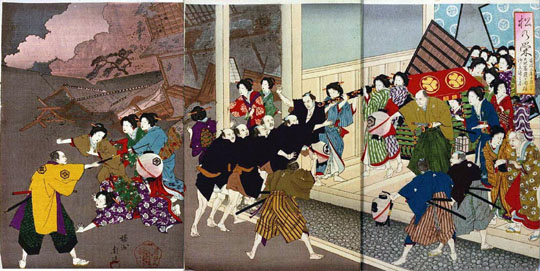

The popularity of ukiyo-e (genre painting) woodblock prints is partly due to aesthetic reasons and partly symbolic ones. In terms of sheer beauty, there is much to recommend in the better examples in the genre, from bright blocks of color and sinuous lines to lively compositions and intriguing details, but a large part of the appeal also comes from what ukiyo-e represents and the emotional content this has for Japanese and foreigners alike.

In symbolic terms, the genre is equated with the timeless world of Edo (present-day Tokyo), which, regardless of its grimmer realities, still manages to exist in our collective imagination as a quaint, charming realm of flowers, geisha, distant views of Fuji, and Edo hustle and bustle, with any unpleasantness reduced to picturesque detail. This rosy image has in large measure been determined by the insistent prettiness of ukiyo-e itself.

Against this strong symbolic correlation, the latest exhibition at the Ota Memorial Museum sets the work of Yoshu Chikanobu, an artist whose career demonstrates that ukiyo-e was not something hermetically sealed within the Edo Period (1603-1867), but had a life that ran well into the more confusing and turbulent Meiji Period (1868-1912).

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.