"Genji Monogatari," known as "The Tale of Genji" in English, is believed by many scholars to be the first full-length novel in world literature. Marking the 1,000th anniversary since its creation, today's Timeout introduces this masterpiece that draws readers into a beautiful world gone by full of passion, pleasures and sorrows of men and women.

But to begin with, skeptics may wonder how the provenance of this medieval tale can be so certainly traced. In fact, though, the diary of its author Murasaki Shikibu, a court lady in the then-imperial city of Kyoto, shows that people were reading the novel in 1008.

In that journal titled "Murasaki Shikibu Nikki," translated as 1996's "The Diary of Lady Murasaki" by Richard Bowring, a paragraph dated Nov. 1, 1008 says:

Major Counselor Kinto poked his head in. "Excuse me," he said. "Would our little Murasaki be in attendance by any chance?''

Here the author was nicknamed Murasaki, meaning "purple" in Japanese, the name of the heroine whom the hero, Genji, loves best.

The novel, which has more than 1,000 pages in its various English translations, includes 41 chapters which chronicle the life and loves of "Shining Genji" and a final 13 chapters that tell stories after his death — primarily concerning Kaoru, falsely regarded as Genji's son, and his various but largely unsuccessful amorous exploits.

In the Heian Period (794-1185) when the tale was written, emperors normally had a number of wives of different status — either consorts or mere intimates — who were daughters of aristocrats. In this way, the aristocrats could have political influence with the emperor and aspire to real power if their grandson was chosen as crown prince.

In the novel, Genji is born the son of the reigning emperor and his best-loved but lowly ranked intimate, who dies while he is still an infant.

Because Genji was a sweet, handsome and intelligent child of the emperor's late love, he becomes the most favored of the ruler's many children. However, as Genji has no family behind him with political clout, the emperor realizes he can't nominate him as crown prince and instead moves him away from court, declares him to be a commoner and — when he gets old enough — appoints him to be a senior government official.

Becoming a commoner has its perks, as this freewheeling status allows high-born Genji to do largely as he pleases — notably consorting with many women.

Portrayed as a perfect hero, Genji has radiant beauty and talents in all the arts. And, because he is also eloquent and extraordinarily passionate, his loves include many ladies of all ages and ranks with different personalities and looks.

Genji's sophisticated charm, and confidence, is well expressed in the chapter "Hana no En (Under the Cherry Blossoms)." Here, in a scene at the inner palace after a cherry blossom-viewing party is over, he happens to meet a woman later called Oborozukiyo (meaning, "the lady of the misty moon"), who is actually a daughter of his political opponent. A 2001 translation by Royall Tyler puts it like this:

He heard a young and pretty voice, surely no common gentlewoman's, coming his way and singing, "Peerless the night with a misty moon . . . " He happily caught her sleeve.

"Oh, don't! Who are you?" she was obviously frightened.

"You need not be afraid.

That you know so well the beauty of the deep night leads me to assume

you have with the setting moon nothing like a casual bond!''

With this he put his arms around her, lay her down, and closed the door. Her outrage and dismay gave her delicious appeal.

"A man — there is a man here!" she cried, trembling.

"I may do as I please, and calling for help will not save you. Just be still!''

She knew his voice and felt a little better.

And so it goes on: Genji has affairs and encounters one after another against the backdrop of his shifting political fortunes. Murasaki paints an intriguing picture as Genji's life and his loves' lives are colored with happiness and sadness.

Hikari Otsuka, an expert on Japanese classics who will publish her translation of "The Tale of Genji" in modern Japanese in November, believes it is this quality of depicting the essence of love explicitly that has made the book so interesting to so many countless readers these last 1,000 years.

"In the novel, love is written about not just as a beautiful thing but as something ugly, too. Some parts of the tale speak of serious love, but other parts tell of flighty affairs," Otsuka said. "And the story also demonstrates how love can be a sword that kills."

In this latter respect, Otsuka points to the tale's first chapter, which explains that the emperor, Genji's father, loves Genji's mother so much that she is bullied by other jealous consorts and intimates and dies due to the stress.

But, as Otsuka adds, readers also can enjoy the tale as a "how to" manual of love, even though the societies then and now are so different regarding love and marriage.

In the Heian Period when the novel was set, ladies of high rank only rarely had the opportunity to leave their residences. So how did they meet men, you may well wonder?

Well, as Genji frequently does, a nobleman would normally hear from servants of a noblewoman how attractive she was. Then, if his interest was aroused, he would send her a love letter in the form of a 31-syllable waka poem. If she, in turn, was moved, then she would write back with a poem in return.

After exchanging poems several times like this, the man would then visit her — but they would be separated by a bamboo blind so he couldn't see her face. From then on, whether he could see her and whether they embarked on a relationship would depend on her feelings and the eagerness he expressed, as well as on the feelings of her parents and close attendants.

If the woman in question was single or a widow, and the lovers eventually married, the man would often still live separately and pay visits to his wife as well as having other wives and lovers. However, because a lady in those days had to always be passive in her relationships with men, her attitude to such domestic arrangements would have great bearing on whether the man kept on loving her.

In the tale, we learn that since his childhood Genji always adored a woman called Fujitsubo, who becomes a consort of his father the emperor because she closely resembles Genji's mother who died. Eventually, Genji manages to have a secret affair with Fujitsubo, and their son later succeeds to the throne.

Fujitsubo attracted Genji for so long because she rarely expressed her love to him, Otsuka says. "If she showed her love toward Genji in obvious ways, she would never have been a woman he pursued and adored forever," she explains.

In comparison, Rokujo no Miyasudokoro (which translates as Rokujo Haven), the beautiful and intelligent widow of a crown prince and one of Genji's older lovers, falls so deeply in love with him that she sends him a letter even though he hasn't contacted her for a long time. However, by so clearly expressing her love, her action played a part in Genji keeping his distance, Otsuka says.

But Rokujo, realizing she is losing Genji's love, and consumed with jealousy over his pregnant wife Aoi, then unconsciously becomes a living phantom and tortures her. Next, in the chapter titled "Aoi (Heart-to-Heart)," Rokujo's phantom possesses Aoi, who becomes critically ill. As many monks gather and pray to rid her of her phantom — without knowing it is Rokujo — Genji comforts her and encourages her to get better. But she replies:

"No, no, you do not understand," a gentle voice answered. "I only wished you to have them release me a little because I am in such pain. I did not want to come at all, but you see, it really is true that the soul of someone in anguish may wander away. The spirit of mine that, sighing and suffering, wanders the heavens, oh, stop it now, tie a knot where in front the two hems meet.''

The voice, the manner, were not hers but those of someone else. After a moment of shock he understood that he was in the presence of the Rokujo Haven.

But in a later scene, Rokujo realizes what she's done and becomes ashamed of herself for having become a phantom. The psychological description of Rokujo in anguish moves readers.

Waki Yamato, the author of "Asakiyumemishi," which means "dreaming shallow dreams," a best-selling comic based on "The Tale of Genji," believes that Rokujo is a mature woman with high pride, and indeed to this day she certainly has plenty of adult female fans.

"Rokujo Haven cannot express her jealousy directly to Genji, so she suffers greatly. Many readers understand her pain," Yamato says.

But the novel's not all so serious. The foolish and yet lovable nature of human beings is also sympathetically described, and is a universal theme running through it that always appeals to readers, Yamato says — likening it in this way to the works of William Shakespeare.

Among all the book's many characters, though, the most foolish is Genji, Yamato declares. In his later years, due to his excessive desire, he loses the trust of Murasaki, his most adored wife who he had brought up from childhood to be his ideal woman.

Murasaki dies in her early 40s and Genji lives on in grief until himself dying in his mid-50s.

The hero's death, though, is not the end of the story. In the last 10 chapters, from the romances of Kaoru, who was believed by almost everyone to be Genji's son, and those of Niou, a grandson of Genji, are narrated.

In this section, starting from Chapter 45, the psychology of the characters, who live in Kyoto itself and in nearby Uji to the south, is explored in more detail than the forgoing sections go into, notes Jakucho Setouchi, a novelist whose modern translation of the work was published in 1996.

"When I read those chapters as a girl, I found the story there similar to the novel 'La Porte Etroite (Strait Is the Gate)" written by [the French 20th-century novelist] Andre Gide," Setouchi said in a lecture she gave in Yokohama last month.

In this section, from Chapter 49 titled "Yadorigi (The Ivy)," Kaoru and Niou become rivals in love after Kaoru happens to see a beautiful princess called Ukifune, whose father hadn't seen her since she was an infant. While Kaoru pursues her, Niou falls for her, too. However, Kaoru consummates his union with Ukifune in Kyoto and moves her secretly to a residence in Uji. But Niou, who is extremely passionate, gets wind of this and visits the house by pretending to be Kaoru — and makes love with her.

Ukifune is then torn between Kaoru and Niou. "She loves Kaoru from her heart but her body is attracted by Niou. The separation of mind and body like this is not written about in the main part of 'The Tale of Genji,' " the comic-book author Yamato says.

Tormented by her conflicting feelings, Ukifune cannot choose between the two men and decides to throw herself into the River Uji. The next day, nobody can find her and it is believed she is dead. However, Ukifune could not commit suicide and, after collapsing under a tree, she is rescued by monks. Then, although she at first suffers from amnesia, she gradually recovers and succeeds in persuading the monks to ordain her as a nun.

But then, a year after Ukifune's supposed death, Kaoru hears a rumor that she is alive and sends her young brother to deliver a love letter from him. Ukifune, though, tells the senior nun that the letter can't be for her and refuses to see her brother. This, of course, disappoints Kaoru, who thinks someone may be hiding her.

And that dear reader, is the end of the tale.

Indeed, the novel certainly does seem to break off lamely in mid-flow and with no conclusion. But the novelist Setouchi said the ending reflects Ukifune's firm decision to decline Kaoru's temptation.

"The ending demonstrates the Buddha accepted Ukifune as a nun," Setouchi said in her lecture. In medieval Japan, people believed women were more sinful than men by nature, but Setouchi said: "I believe Murasaki Shikibu reached the conclusion that women can attain Buddhahood [by being liberated from worldly desires and spiritually awakened]."

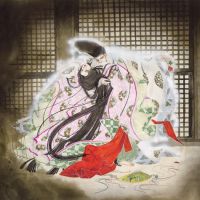

Yokohama Museum of Art is holding an exhibition titled "A Thousand Years of The Tale of Genji — The Timeless Allure of Courtly Romance" until Nov. 3, and visitors will be able to see most of the historical pictures accompanying these articles. The museum opens from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (until 8 p.m. on Fridays), and closes on Thursdays. Admission is ¥1,300 for adults and ¥700 for students. The museum is a 10-minute walk from Sakuragicho Station on the JR Keihintohoku Line, and a three-minute walk from Minatomirai Station on the Yokohama Municipal Subway. For more information, visit www.genji1000.jp/english/

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.