With a falling population, a shrinking tax base and a shortage of carers for its increasing number of elderly, calls are growing for Japan to allow in a large influx of foreign workers to plug the gap. The question is: When they come, will they be able to find a place to stay?

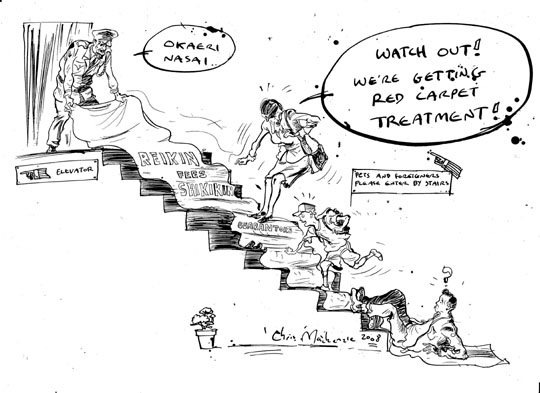

With its "shikikin" (deposit) and "reikin" (key money) — which mean forking out several months' rent upfront and tracking down a guarantor willing to take on the payments in case of default — Japan's real estate system is notorious for the high demands it makes of potential tenants. Even if an individual is able to pay all the fees and find a guarantor, foreigners often hit a brick wall when looking for a place to live simply because they are not native-born Japanese.

John Clark, a Canadian translator with permanent residency status who has been living in Japan since 1999, ran head-first into that barrier when he was looking for an apartment in downtown Hiroshima. Despite having a guarantor, sufficient funds and being fluent in Japanese, the building owner refused to even consider letting him rent the room.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.