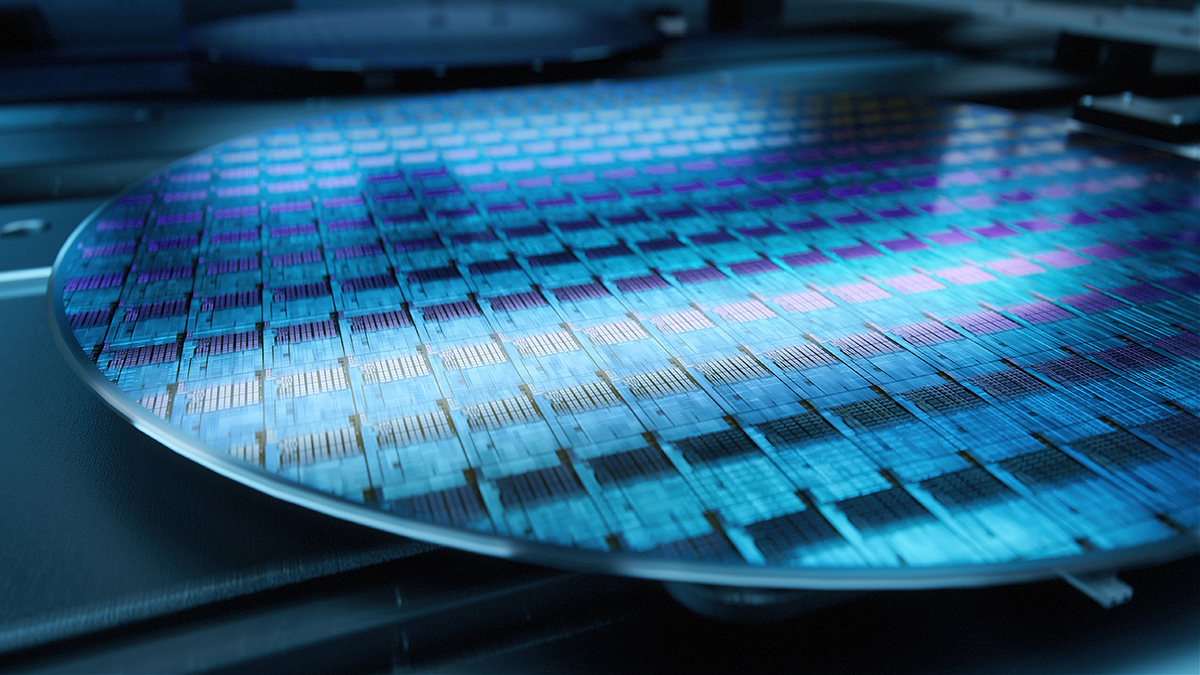

The Japanese semiconductor industry is on the cusp of a revival, with major national backing for players including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., a world-leading chipmaker that is setting up plants in Japan, and Rapidus, a new cutting-edge domestic chipmaker.

The Japan Times interviewed University of Tokyo professor Tadahiro Kuroda about why Japan’s once respected semiconductor industry has declined and how Japan aims to achieve a turnaround and position semiconductors as a national strategic commodity.

Kuroda, who holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, stated that the Japanese semiconductor industry has undergone three phases over the past nearly half-century.

“The first stage was the 1980s, when Japan accounted for over half of global semiconductor production. Japan’s dominance in the memory chip market was particularly pronounced until around 1995, right before the rapid proliferation of computers started,” he said.

The second phase was marked by an intensification of trade friction with the United States. “Semiconductor technology was originally developed in the United States, but Japan worked assiduously to gain a competitive advantage. U.S. discontent with this situation led to it becoming a political issue, which in turn resulted in the 1986 U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement. This agreement included antidumping measures and numerical targets designed to protect the semiconductor industry in the United States.

“The trade friction was a trigger but not the ultimate cause of the decline of the Japanese semiconductor industry. As the semiconductor industry grew, the amount of investment required increased from billions (of yen) to tens of billions and hundreds of billions, beyond the resources of Japanese electronics manufacturers,” he said.

Kuroda also highlighted Japan’s relative weakness in developing business models for virtual spaces, noting that the country’s strength lies in manufacturing products that ensure consumers’ comfort in physical environments.

By the time China replaced Japan as the target of U.S. trade ire, Japan was no longer considered an enemy of the United States. “In addition to the improvement of the Japan-U.S. relationship, Japan’s semiconductor industry began to receive government support from the perspective of national security, marking the third phase of the industry’s history. Japan remains one of the top countries in the world in terms of gross domestic product, although there has been a decline in recent years. If the nation were to concentrate investment in this field, we could still make a difference,” Kuroda explained.

The kind of semiconductor chip most needed in this era is one that can be used in technologies that integrate the real world and virtual space. Kuroda suggested that Japan could make various contributions in this field.

“Sony boasts the biggest share of the global market for image sensors and Japan also excels in manufacturing the power electronics used in motor drives,” he said.

“Japan is still good at making things used in the real world. But it loses to the U.S. in making artificial intelligence calculate at a breakneck speed in a virtual space. The two countries bringing their strengths together for the development of today’s semiconductors is where I see the hope for Japan’s resurgence in this field,” he said.

He stressed that this kind of bilateral and multilateral collaboration is indispensable not only for the success of Japan’s semiconductor industry, but also for securing a stable supply of chips for the international community.

“The major setback that the industry experienced in the past is largely attributable to the strategy to become the only winner in the global market. We should focus not on how to sell more than anyone else, but on how to continue providing a stable supply of semiconductors that are now used in everything from household electronics that we use every day to high-tech machines, as well as on producing what other countries have difficulty making,” he said.

He also said that the complexity of today’s semiconductor technology and the size of the industry make it unlikely that a single entity will monopolize the market. This is driving the need for global collaboration.

The substantial subsidy of over ¥1.2 trillion ($8.2 billion) provided by the Japanese government to TSMC represents an example of such an international collaboration. It demonstrates the company’s commitment to investing in its facilities and business within Japan.

“This kind of investment requires a stronger commitment than joint research or joint development because it is more difficult to withdraw from,” Kuroda said. He also highlighted the importance of having domestic production capacity within the extensive network aimed at supplying semiconductor chips to Japan.

On the other hand, the government is also investing in Japanese enterprises. Kuroda assured critics that supporting both TSMC and Rapidus at the same time is not contradictory.

“TSMC in Kumamoto will specialize in the technology intended for making chips for products that make up the largest market segment, such as cars, home electronics and other items that are necessary for people’s daily lives,” he said, noting that these are the kinds of semiconductors that are needed now and in abundance from the perspective of economic security.

The most advanced ones are for data centers and AI. “That is where research and development is most needed because of the vertiginous speed of the technology’s advancement. Rapidus is designed to play this part,” Kuroda said.

It takes enormous energy to draw out the semiconductor performance required to run state-of-the-art AI operations.

“Considering the situation where electricity consumption is already increasing rapidly with the use of advanced technology and the necessity of cooling servers and other equipment, we need to increase the efficiency of semiconductors. That will allow more calculation to be done using the same amount of energy, or less energy to be consumed to do the same amount of calculation,” he said, stressing that doing business in greener ways is essential to win the trust of the global market.

Kuroda thinks that Japan still has a chance in this part of the semiconductor market despite the period of over two decades of no investment and no progress in the industry.

“Why? It is because of the typical conventional personnel system of Japanese companies that does not lay off workers easily,” he said.

He explained that some semiconductor experts who remained in companies such as electronics manufacturers continued attending academic conferences and learning from the latest research on semiconductors even after their companies withdrew from the business. “Those are the people who gathered to Rapidus,” he said.

“In addition to the existing experts, we need to educate the young talent that will be the next-generation leaders in this field. That is why the University of Tokyo formed an alliance with TSMC and signed an agreement with Kumamoto University,” he said.

For those engineers diverted by Japan’s two-decade slump, the Fukuoka Semicon-ductor Reskilling Center, headed by Kuroda, opened in Fukuoka last year to help them relearn their skills.

“Working remotely is an option for some of the positions that could only be covered by employees working three shifts on site in the past. This helps achieve greater diversity in human resources that today’s chip industry needs,” Kuroda said. This need for diversification of human resources is what prompted him to accept the position of chancellor of the Prefectural University of Kumamoto this spring.

“The focus of the university, which does not have a faculty of engineering, is to nurture people with good international communication skills,” which are necessary for an industry involving increasing international collaboration. He also said that the university’s Faculty of Environmental and Symbiotic Sciences will provide a unique strength at a time when the industry needs to address water and other environmental issues.

As the AI era unfolds, Kuroda stated that the coevolution of AI and semiconductors occurring with no human in the loop is becoming a realistic prospect, whereby AI will begin to design the chips that drive it.

“It is our human ingenuity that drives the creation of new services and technologies using semiconductors to enhance the quality of life and ensure societal stability,” he pointed out. Noting that new ideas emerge when diverse people gather and converse, he said: “That is what universities are for, and they need to continue their effort to attract brains at home and from abroad.”

The revival of Japan’s semiconductor industry depends on a long-term and comprehensive effort including human resource development, international collaboration and continuous government support.

This article was originally published in the Kyushu Semiconductor Special on Sept. 25.