Recently celebrating its 170th anniversary, Cheltenham Ladies’ College has been a bastion of education for girls and young women ages 11 to 18. From its Victorian roots to its role today as a global educational leader, with students from over 40 countries and 80% of them boarding, CLC continues to evolve under the guidance of its 11th principal, Eve Jardine-Young. In an interview, she shared insights into the college’s enduring legacy, its pioneering connections with Japan and the ongoing challenge of preparing students for an unpredictable future.

Tradition as a catalyst

Jardine-Young emphasized the value of tradition not as a constraint, but as a source of courage and belonging by connecting students with the past and those who came before. “There’s this idea of ‘cherishing’ that I think is crucial. We don’t value traditions out of a sense of obligation, but out of free will. Once upon a time, these great women that came before us were 11 years old as well, and grew to be amazing leaders, taking it one day at a time,” she said.

While tradition is a cornerstone of Cheltenham’s identity, Jardine-Young is mindful of the potential pitfalls of an overreliance on it. Schools as old as Cheltenham that have a rich, inspirational history can “be the handbrake on how fast you can move and adapt,” she acknowledged. “Something that enriches you can also be heavy baggage. As the years clock by and more tradition is behind you, you have to be more intentional about what you leave behind and what stays with you.”

She is keenly aware of the tension between preserving these traditions and embracing innovation, admitting that CLC has had difficulty at times in distinguishing between traditions that align with its core educational values and those that are simply habitual. “The appetite is to keep adding more and more to the shopping trolley and not take anything out,” she illustrated. Adapting new ideas and simultaneously considering what could be relinquished while maintaining CLC’s roots is a constant challenge.

The COVID-19 pandemic tested this balance in unprecedented ways. As children were quarantined at home and schools scrambled to adapt, Cheltenham, as a boarding school, faced the additional challenge of maintaining its high standards across multiple time zones. “We were forced through crisis into a period of digital galvanization. We had to rise to the challenge, having no road map nor traditions whatsoever,” she recalled.

But when the pandemic began to abate and the college resumed face-to-face schooling, the students craved a return to the traditions that had been seized from them. “The Christmas panto, the Wednesday morning anthem — I believe these were the primal sense of reassurance that normality is returning,” she said. The survival of traditions through some of the most tumultuous moments of history — from the bombing of a part of the school during World War II and the COVID-19 pandemic — shows that “they are in the hearts and minds of the students. For me, those traditions have earned their place in our modern experience.”

Shared intercontinental vision

The college’s relationship with Japan dates back to the 19th century, a time when women’s education was still a radical concept. Under the stewardship of Dorothea Beale (“Miss Beale”), principal from 1858 until the day she died in 1906, the school became a symbol of female empowerment. Beale’s influence extended far beyond British borders, reaching reformers like Utako Shimoda and Umeko Tsuda, who were likewise instrumental in establishing the foundations for women’s education in Japan.

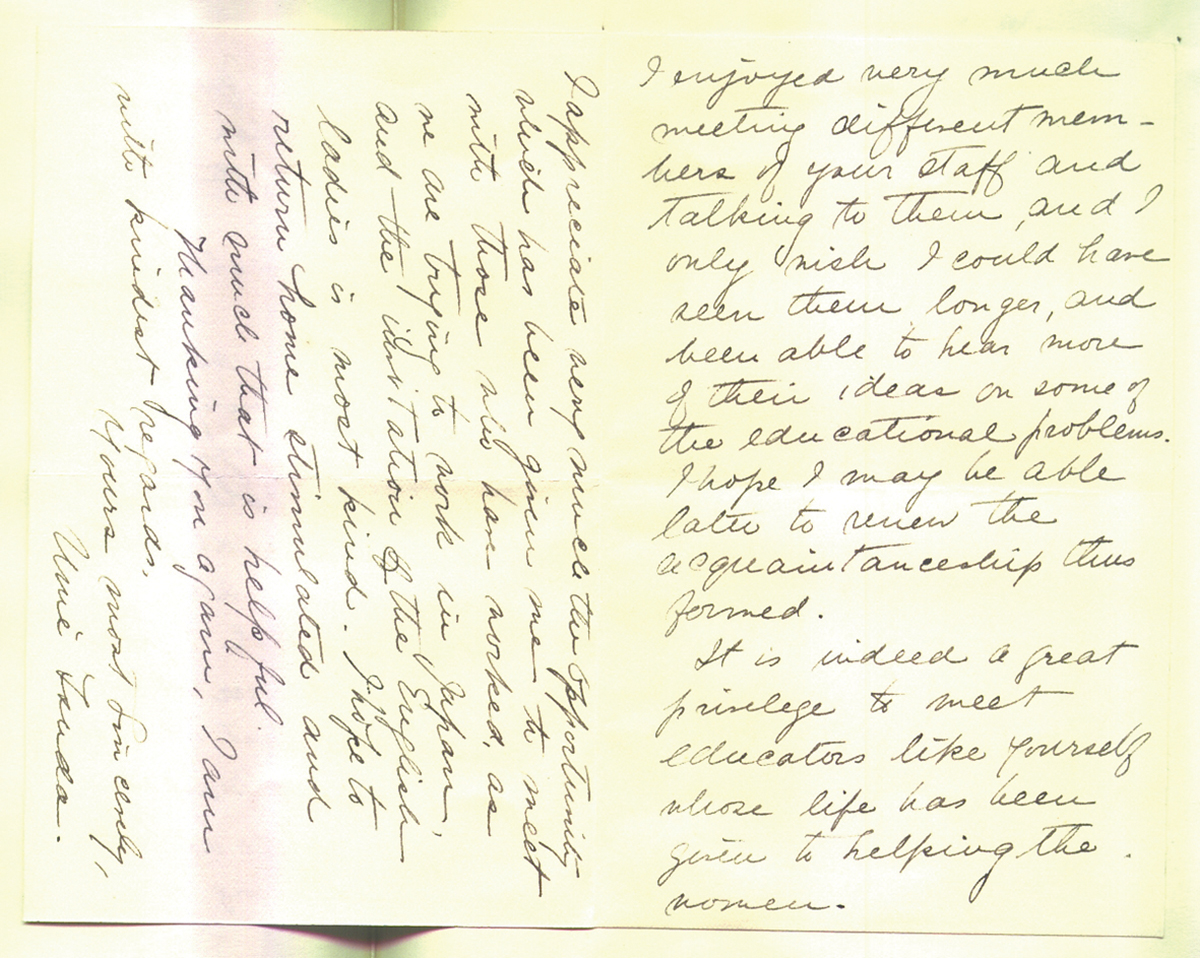

In the 1890s, Shimoda and Tsuda both visited Cheltenham Ladies’ College as part of a Japanese government initiative to study Western practices regarding women’s education. CLC Archivist Georgina Robinson showed one of several volumes of letters entitled “Letters to Miss Beale from Famous People” in which exchanges between Beale and her Japanese counterparts are included. One letter from Tsuda thanked Beale for her hospitality and tour of the college. She wrote that “it is indeed a wonderful institution and a living symbol of the progress of your women during the last 30 or 40 years. May we in Japan do as much in the coming ones.” After returning to Japan, Tsuda founded the famous Tsuda University, inspired by what she witnessed while abroad.

Beale’s correspondence with these Japanese reformers was more than just an exchange of letters. It was a dialogue about inclusivity and the future of women’s roles in global society. “When you consider the existing asymmetry of the genders in virtually every country, the work is not finished,” Jardine-Young averred. “We’re not just forward-looking for the sake of it. It is about our shared endeavor to try and build a more open and inclusive set of opportunities for our children.”

Cheltenham’s influence persists in Japan today through ongoing partnerships with sister schools. The college hosts a summer school program for students from five Japanese girls schools in which they spend two weeks in Cheltenham, visit Stratford-upon-Avon — the birthplace of Shakespeare — and become members of CLC’s flourishing international community.

Encouraging women in STEM

When it comes to women’s education, the relatively low number of women in STEM fields is a constant point of concern. CLC strives to provide a holistic education that includes these topics, pushing against gender stereotypes since its founding days. “Our founders — four fathers of daughters — were united in their determination to create a more equitable beginning,” Jardine-Young noted. “They asked, ‘Why can’t our daughters study maths and science?’” and set out to “educate their minds” regardless of barriers to entering the workforce.

At Cheltenham, things are different. “It just doesn’t occur to anyone here that they can’t do anything. The most popular subject studied here is maths,” Jardine-Young said, adding that students’ interest in STEM persists into their upper-level studies even when the courses become optional. As evidenced in photographs taken as early as 1876 and up to the present day, the college has placed science and math “on equal footing” with other subjects despite there being historically a dearth of employment opportunities for women.

With a background in engineering, Jardine-Young believes that a solid foundation in the sciences provides invaluable skills regardless of where a student goes in life. “STEM forces zero tolerance for errors. When you take that into areas of more subjective thinking, it’s good for your mind to have that discipline,” she explained. She drew a comparison to her mother, who can play the piano by ear but never acquired the ability to read music. “She is so frustrated because she can only ever get to a certain ceiling,” she said. Lacking a bottom-up analytical framework like STEM offers can severely limit a student’s potential elsewhere.

Preparing for uncertain future

“The further out in time you go, the less clear I am about the world we are trying to prepare students for,” Jardine-Young said. Citing issues from the threat of climate change and the growth of divisive politics to the rapid rate of technological developments, she sees many challenges ahead. But amid the fog-shrouded future, she is hopeful that education and the younger generation can play a decisive role in designing better futures.

She believes that the students of “Gen C” — the COVID generation — may have acquired a resilience and skill set during the pandemic that will grow more apparent over time. “We haven’t yet found our way to the language to describe the strengths of weathering COVID,” she said. She is excited about what they will bring to the table when they become adults and the world is faced with another global crisis such as climate change: “They won’t have the same set of assumptions that we have about what is possible, and their shared experience will inform their courage and their potential ability to collaborate.”

Despite an unclear outlook, it is still the task of schools to prepare students as best they can, and in Jardine-Young’s mind, Shakespeare said it best: “The readiness is all.” Being paralyzed by uncertainty is unacceptable. “We have to get better at making decisions that are still thoughtful, but with imperfect information,” she asserted. As for CLC’s role, she endeavors for it to be “a place where we welcome girls with the potential and appetite to try, to be responsive, to be challenged, not to just be leaders, but to be capable of leadership — to understand the relational choreography that is not just all about ‘me,’ but also about followership and allyship.”

One thing she is certain of, however, is the timelessness and importance of engaging with values central to humanity.

She traced a direct line from Dorothea Beale and the school’s legacy up to the present day. Beale “sat here with those Japanese guests, and they talked about the world — about love, family, justice, opportunity, happiness, striving and need. … And those are the same values we’re discussing today, and will also in the future.”