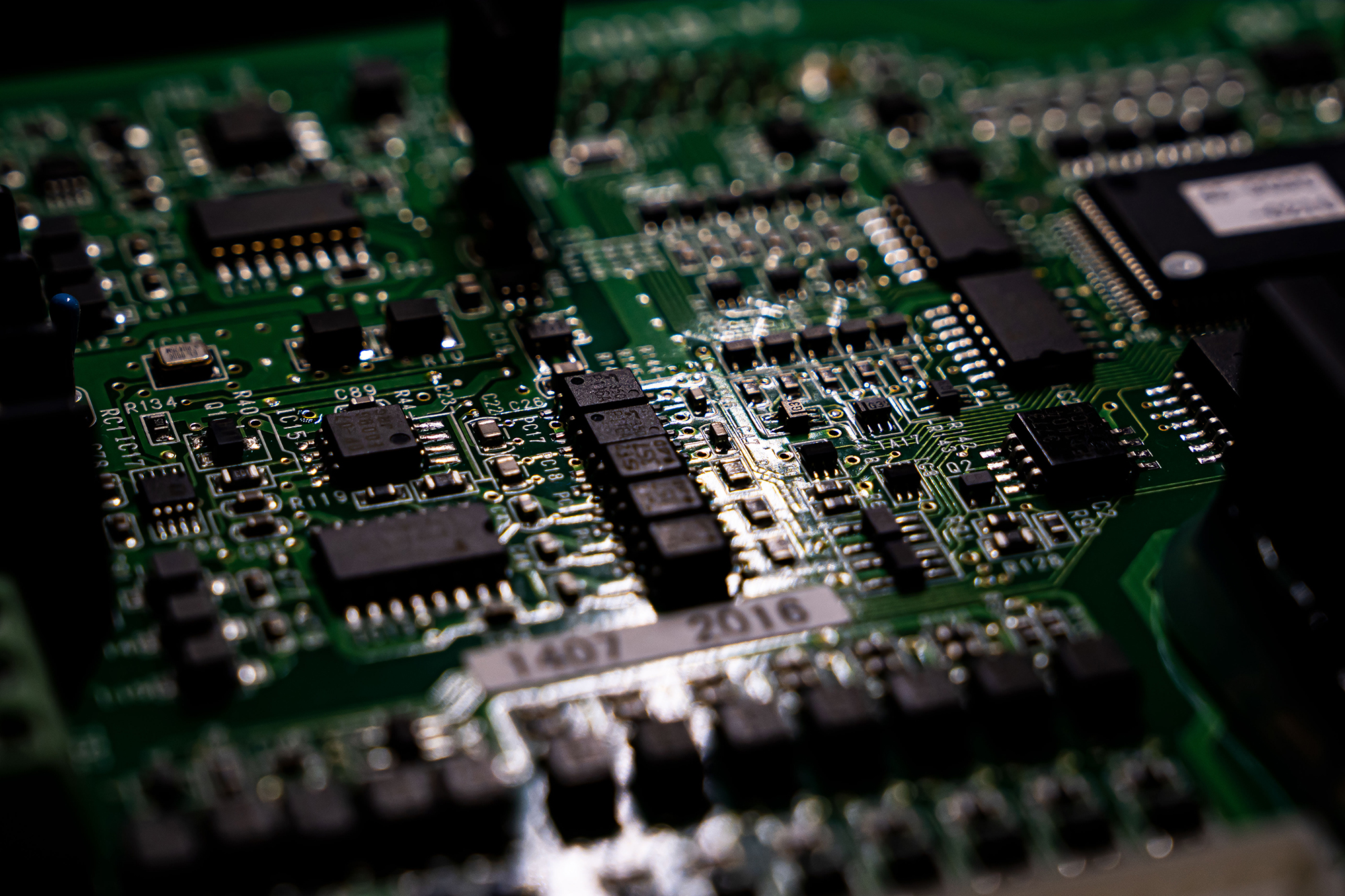

The Japanese semiconductor industry is on the cusp of a revival, with a major national backing for players including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., a world-leading chipmaker that is setting up plants in Japan, and Rapidus, a new cutting-edge domestic chipmaker.

The Japan Times interviewed University of Tokyo professor Tadahiro Kuroda about why Japan’s once respected semiconductor industry has declined and how Japan aims to achieve a turnaround and position semiconductors as a national strategic commodity.

Kuroda, who has a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, said the Japanese semiconductor industry was doing very well until around 1995. In 1988, 50.3% of the world’s semiconductors were made in Japan. “Those chips were used in consumer electronics such as TVs and videos, which were also considered Japan’s strength,” he said.

However, trade friction with the United States began casting a shadow on the industry and Japan’s market share eventually dropped to 10% by 2019.

“The trade friction was a trigger but not the ultimate cause. As the semiconductor industry grew, the amount of investment required increased from billions (of yen) to tens of billions and hundreds of billions, beyond the resources of Japanese electronics manufacturers,” he said.

He also pointed out that the slump overlapped with the rapid growth in computer and smartphone usage.

“These devices deal with virtual spaces. Japan has not been very strong in business models concerning virtual spaces while it has been good at the type of manufacturing that requires the pursuit of minute details to achieve people’s comfort in real space,” he said.

But China gradually replaced Japan as the target of U.S. trade ire and their confrontational relationship was defined during former President Donald Trump’s administration, which again led to heated competition in semiconductors between the countries.

“For the U.S., Japan was not an enemy anymore. In addition to the improvement of the Japan-U.S. relationship, Japan’s semiconductor industry started to receive the blessing of the government from the perspective of national security,” Kuroda explained.

The kind of semiconductor chip most needed in this era is one that can be used in technologies that integrate the real world and virtual space.

“Take self-driving technology, for example. In an instant, it completes the entire process of rotating the motor of a tire based on the optimum solution produced by future prediction based on the analysis of big data using sensors, “digital twins” and other kinds of technologies,” he said.

He went on to say that Sony boasts the biggest share of the global market for image sensors and that Japan also excels in manufacturing the power electronics used in motor drives.

“As such, Japan is still good at making things used in the real world. But it loses to the U.S. in making artificial intelligence calculate at a breakneck speed in a virtual space. The two countries bringing their strengths together for the development of today’s semiconductors is where I see the hope for Japan’s resurgence in this field,” he said.

He stressed that this kind of bilateral and multilateral collaboration is indispensable not only for the success of Japan’s semiconductor industry, but also for securing a stable supply of chips for the international community.

“The major setback that the industry experienced in the past is largely attributable to the strategy to become the only winner in the global market. We should focus not on how to sell more than anyone else, but on how to continue providing a stable supply of semiconductors that are now used in everything from household electronics that we use every day to high-tech machines, as well as on producing what other countries have difficulty making,” he said.

The massive subsidy of over ¥1.2 trillion ($8.2 billion) granted by the Japanese government to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing is significant in that it secures a commitment by the company to invest in its facilities and business within Japan’s borders. Kuroda emphasized that it is important to have production capacity within the vast network aimed at supplying semiconductor chips to Japan.

He also pointed out that the expectations of the world, especially Western nations, for Japan are growing in terms of securing the chip supply network mainly because of geopolitical risks.

On the other hand, the government is also investing in Japanese enterprises. Kuroda assured critics that supporting both TSMC and Rapidus at the same time is not contradictory.

“TSMC in Kumamoto will specialize in the technology intended for making chips for products that make up the largest market segment, such as cars, home electronics and other items that are necessary for people’s daily lives,” he said, noting that these are the kinds of semiconductors that are needed now and in abundance from the perspective of economic security.

The most advanced ones are for data centers and artificial intelligence. “That is where research and development is most needed because of the vertiginous speed of the technology’s advancement. Rapidus is designed to play this part,” Kuroda said.

It takes enormous energy to draw out the semiconductor capacity required to run state-of-the-art artificial intelligence operations.

“Considering the situation where electricity consumption is already increasing rapidly with the use of advanced technology and the necessity of cooling servers and other equipment, we need to increase the efficiency of semiconductors. That will allow more calculation to be done using the same amount of energy, or less energy to be consumed to do the same amount of calculation,” Kuroda said, stressing that doing business in greener ways is essential to win the trust of the global market.

Kuroda thinks that Japan still has a chance in this part of the semiconductor market despite the period of over two decades of no investment and no progress in the industry. “Why? It is because of the typical conventional personnel system of Japanese companies that does not lay off workers easily,” Kuroda said.

He explained that some semiconductor experts who remained in companies such as electronics manufacturers continued attending academic conferences and learning from the latest research on semiconductors even after their companies withdrew from the business. “Those are the people who gathered to Rapidus,” he said.

He went on to say that Japanese know-how is one of the major reasons why TSMC and other foreign enterprises come to Japan.

“In addition to the existing experts, we need to educate the young talent that will be the next generation leaders in this field. That is why the University of Tokyo formed an alliance with TSMC and signed an agreement with Kumamoto University,” he said.

For those engineers diverted by Japan’s two-decade slump, the Fukuoka Semiconductor Reskilling Center, headed by Kuroda, opened in Fukuoka last year to help them relearn their semiconductor skills.

“Working remotely is an option for some of the positions that could only be covered by employees working three shifts on site in the past. This helps achieve greater diversity in human resources that today’s chip industry needs,” Kuroda said. This need for diversification of human resources is what prompted him to accept the position of chancellor of the Prefectural University of Kumamoto this spring.

“The focus of the university, which does not have a faculty of engineering, is to nurture people with good international communication skills,” which are necessary for an industry involving increasing interstate collaboration. He also said that the university’s Faculty of Environmental and Symbiotic Sciences will provide a unique strength at a time when the industry needs to address water and other environmental issues.

As the era of artificial intelligence unfolds, “It is us human beings who think what to do and what services to create using semiconductors to make people happy and to make society safe and comfortable,” he said. Noting that new ideas emerge when diverse people gather and converse, he said: “That is what universities are for, and they need to continue their effort to attract brains from both home and abroad.”

The revival of Japan’s semiconductor industry depends on a long-term and comprehensive effort by the industry, including human resource development, international collaboration and continuous government support.