The Japanese cypress, known as hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtuse), has been used since ancient times to make buildings, especially important structures such as castles, palaces, shrines and temples, in addition to fixtures and furniture. The popular Japanese cedar, or sugi (Cryptomeria japonica), has been used for multiple purposes as well, supporting the nation’s people and culture.

Known for a variety of advantages, from their strength and refreshing scents to the way they are grown and managed in planted forests, Japanese trees are attracting growing attention from the lumber industry.

To explore its international market potential, the Japan Wood-Products Export Association obtained certification on the design strength of hinoki two-by-four dimension lumber from the American Lumber Standard Committee in April. This is expected to serve as a starting point for sales of other kinds of lumber, especially sugi, to meet global demand without compromising natural forests.

The association is a nonprofit that focuses on supporting municipalities, organizations and companies interested in improving international sales of Japanese wood through marketing research, seminars, training sessions, performance validation and information sharing on the standards and regulations of target countries.

In a recent interview with The Japan Times, Japan Wood-Products Export Association Chairperson Hisao Yamada shared his knowledge and insights about the characteristics of Japanese cypress and cedar, the process of getting certified to export lumber to the United States, and the future of the Japanese lumber and forestry industries.

Yamada, a former civil servant who spent 33 years at the Forestry Agency and other public offices and served as director-general of the agency’s Kyushu and Hokkaido offices, has chaired the association since 2021. In addition to contributing to academia through books and articles, he served as a visiting professor at Kagoshima University.

Hinoki: Dense, tough, healthy

Hinoki is known for producing high-grade lumber that is dense, durable and imbued with a refreshing coniferous scent. The cypress grows on Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu. Many of the best known varieties are named after the areas where they are grown, such as Kiso, in the upper reaches of the Kiso River extending to Nagano and Gifu prefectures, and Yoshino, part of Nara Prefecture.

Hinoki is mainly used as a high-quality building material especially for foundations, posts, beams, wall boards, floorboards and furniture. Because it has a high tolerance to water and moisture, it is used for making bathtubs and saunas, too.

Many major shrines and temples, including the famed Todaiji Temple originally built in Nara in the eighth century, and Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture, were built with hinoki. Hinoki is also used in many parts of Nara’s Horyuji Temple, which hosts over 50 buildings that have been designated as national treasures and important cultural assets. The fact the temple has been standing for more than 1,300 years is proof of hinoki’s durability.

According to the association, the high density of this cypress contributes to easy and precise processing. It also dries well, has high resistance to wear and is easy to glue together or paint. The grain is relatively fine and even, making cut surfaces smooth.

Some of the natural active ingredients of hinoki are said to be capable of fighting odors and absorbing harmful substances, such as formaldehyde. According to the association, the phytoncides emitted by hinoki are antimicrobial, detrimental to termites and capable of activating the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps people relax by lowering blood pressure and increasing alpha wave generation in the brain.

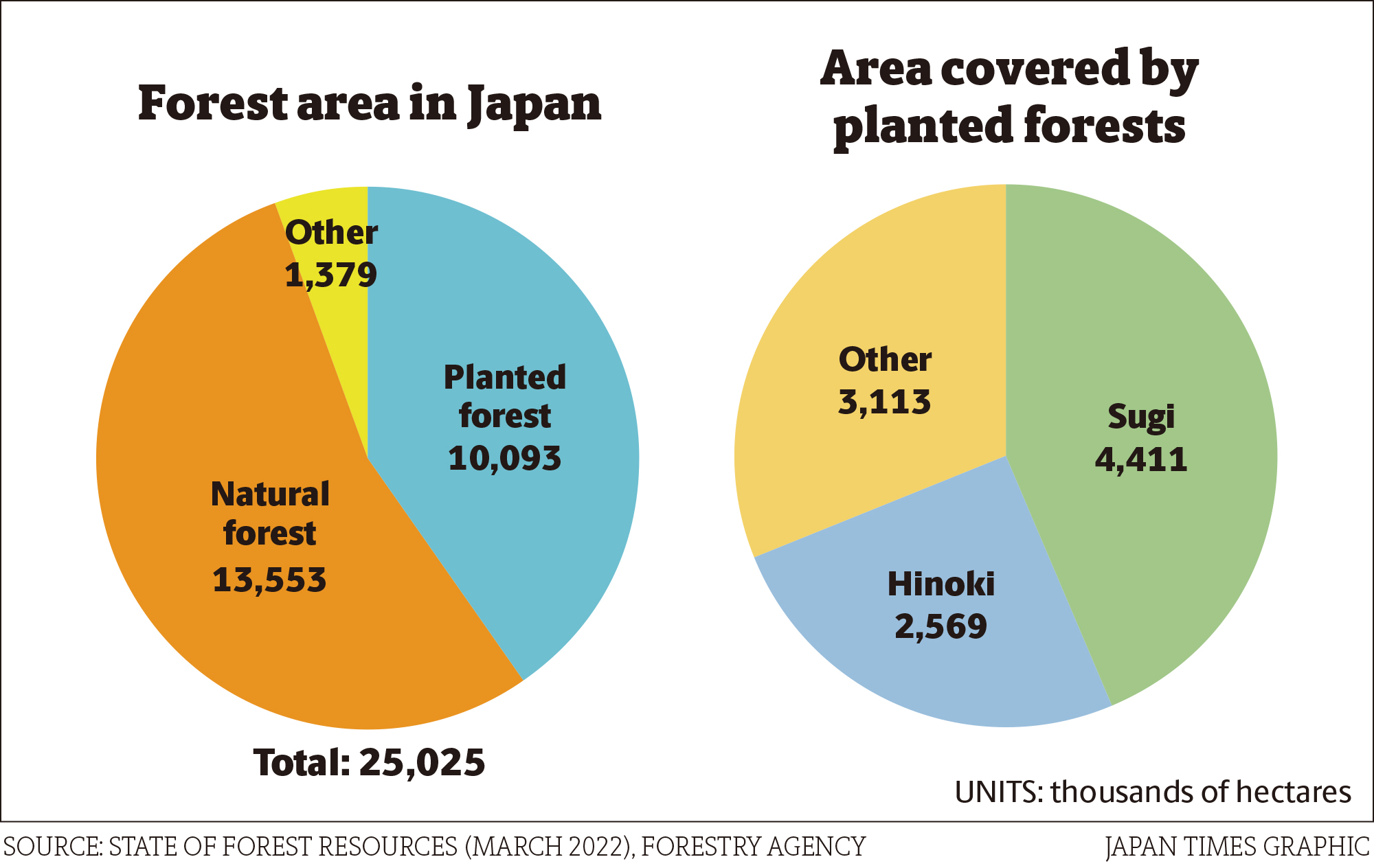

A majority of this excellent lumber resource is now available for use. Hinoki is said to become mature enough to harvest in about 50 years. According to the latest statistics from the Forestry Agency, published in 2022, Japan has about 2.57 milion hectares of hinoki under management, with about 54% over 51 years old. The history of planted forests in Japan, however, is much longer.

“It has been several centuries since our country started to plant forests,” Yamada said. He explained that wet weather combined with the narrow contours of the land to make Japan’s mountains steep and its rivers short and rapid. This meant rivers became the ideal routes for transporting timber from the mountains to coastal areas.

“That is why it was possible to supply timber at low costs for the construction of castles and other buildings across the country,” he said. “However, because transportation changed to railways and trucks in the 20th century, timber suppliers were able to gather lumber from greater distances.”

Logging’s slump and revival

There have been times in the past when large quantities of wood were needed, throwing the industry into turmoil.

“Japan’s rapid postwar reconstruction led to timber shortages and price hikes. The liberalization of the lumber trade that was gradually promoted in response was completed in 1964, allowing large amounts of cheap and standardized lumber to enter the Japanese market,” Yamada said.

Changes in construction methods and housing design spurred the use of imported lumber. Yamada explained that carpenters in Japan traditionally adjust the sizes and shapes of timber at construction sites, but the advancement of the “pre-cut method,” supported by the arrival of computer-aided design systems, made it possible to prepare the exact numbers and shapes of wood materials needed to make a building based on its blueprint in advance.

“All you need to do at a construction site is to assemble them together, which is convenient. But to make this possible, the processed wood materials cannot have the slightest warping,” he explained.

“While Japanese traditional wooden houses were made to allow a natural breeze to pass through, modern houses turned into airtight, insulated and quake-resistant boxes with the widespread use of air conditioners,” Yamada said, adding that it made little sense to use hinoki for these structures because all the wood gets sealed inside the walls.

For these reasons, demand for imported, laminated lumber made with layers of thin, dry boards that were resistant to warping increased. In contrast, demand for domestic timber slumped and Japan’s self-sufficiency rate plunged to a record low 18.8% in 2002, according to Forestry Agency statistics. But an effort to reduce costs by expanding the size of domestic lumbermills gradually paid off, and the lumber self-sufficiency rate recovered to 40.7% in 2022, making Japan’s lumber competitive again.

Yamada said that Japan’s lumber now has enough of an advantage to compete globally in terms of quantity, quality and price. This is not only beneficial for Japan, but for the rest of the world as well. “It is risky to rely on only a few lumber-exporting countries. We have seen problems concerning lumber supplies due to various reasons,” he said.

Whether from war, disease or insect damage, every country faces risk when trading lumber, and Yamada believes that the more choices there are, the fewer risks the global market will face.

For example, the U.S. saw major wood shortages and price hikes in 2021. The main reasons were said to be labor shortages in the supply chain, including highly trained wood processors and truckers, as well as a slowdown in external shipping caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, demand for wood was high due to the boom in the housing, renovation and remodeling industries driven by the pandemic.

“The U.S. relied on some European countries that could provide wood products that had already met American standards,” Yamada said.

Now that hinoki two-by-fours have been certified, Japan can contribute to relieving future shortages as long as it’s competitive enough to meet the needs of the markets outside Japan. But Yamada emphasized that what is more important than merely enhancing Japan’s competitiveness is to create more options for importing wood products so Japan can contribute to mitigating shortages whenever and wherever they happen.

Since lumber shortages are more likely to occur outside Japan, it is important to make an effort to promote exports. According to 2023 data from the Statistics Bureau, Japan’s declining birthrate and rapidly graying population have caused its population to shrink for the past 13 years. However, the global population is rising and expected to approach 10 billion in 30 years, based on the latest forecast by the United Nations. There are countries with pressing demands for housing due to population growth, immigration, or damage from disasters and conflicts. Yamada, who has traveled across the world to learn about forestry, has seen people living with no roofs over their heads and thinks that any solution needs to be affordable and sustainable.

“I think that the demand for timber has been growing in parallel to the increase in the world population and the global GDP (gross domestic product). It is the responsibility of the entire forestry industry to supply the timber needed to meet this demand from well-managed forests, and I believe that Japan can play a part in it,” Yamada said.

Conservation pays off

While Japan has been harvesting timber from planted forests for centuries, there were many countries in the 20th century that exploited natural forests.

“In the 21st century, people started to realize the finite nature of the Earth. With the rising fears and awareness of resource depletion, the world has been shifting away from cutting down natural forests and trying to achieve a stable supply of timber from planted forests,” Yamada said.

According to The State of the World’s Forests, a comprehensive report on forests and conservation published in 2020 by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, the total of the world’s forested areas comes to 4.06 billion hectares and the area of forest designated primarily for production is estimated at 1.15 billion hectares in the 160 countries, representing 93% of the world’s forest area. However, about 93% of the total of the world’s forested areas is made up of naturally regenerating forests and planted forests account for only 7%. But not all of that is for logging.

The report states that approximately 45% of the planted forests are plantation forests mainly composed of one or two tree species of equal age managed for productive purposes, similar to the planted forests that have been managed in Japan. The other 55% of planted forests are intended for ecosystem restoration and protection of soil and water.

“The 10 million hectares of planted forests that Japan created in the postwar period accounts for as much as one-thirteenth of the total planted forest area available for commercial use worldwide,” Yamada said. “Of the 10 million hectares, 4.4 million hectares of sugi, 2.6 million hectares of hinoki, 1 million hectares of Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi) and 0.7 million hectares of todo fir (Abies sachalinensis) would be especially useful.”

Japan’s role is to utilize these resources to contribute to the lives of those who can benefit, Yamada said.

However, wood materials are not something that can be exported anywhere overnight, and Japan has been paving the way for this sales campaign by getting ahead of the red tape.

“We needed to have our timber evaluated based on objective criteria. That is why we began preparing to have Japan’s cypress dimension lumber certified by the American Lumber Standard Committee about five years ago, which bore fruit this April,” Yamada said.

Targeting global markets

Although each country has its own set of standards for importing lumber, Yamada sees the acquisition of an American certification as a precedent for approaching other countries in the future. With the aim of entering the global market, the association chose to proceed with its hinoki marketing push in the U.S.

“The reason why we chose this wood was because there are a few tree species similar to cypress in the United States whose data are available. Having counterparts that we can refer to make a comparison has enabled easier and faster completion of testing and evaluation,” he said.

The association is also aiming to get sugi certified by the American Lumber Standard Committee next year, even though it outranks hinoki in terms of plantation area. The reason why the association put hinoki first is because the cedar is an endemic species in Japan and lacks data for comparison in the U.S.

“Actually, sugi has a price edge over hinoki,” Yamada said. Based on the most recent data published by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the price difference between a 10.5 centimeter by 10.5 centimeter 3-meter piece of sugi after it is processed and dried is ¥19,000 cheaper than processed and dried hinoki of the same size. The price difference is even bigger when the timber is not dried — sugi is ¥22,600 cheaper than hinoki.

Yamada quickly cited the many advantages of Japanese cedar.

“It can be processed easily. It cuts well in the direction of fiber, but it is also elastic at the same time, so it does not break easily. It doesn’t rot easily and it is highly transportable because of its lightness.”

The decline in the availability of western red cedar often used for fences and decks in the U.S. is generating interest in sugi as an alternative.

Yamada said hinoki and sugi have many uses aside from dimension lumber. Both can be used for interior work ranging from walls, flooring and paneling to fixtures and furniture.

Looking to the future

Yamada is excited about the future of Japanese lumber beyond its current expansion to the U.S. market.

“The country that has been facing the greatest shortage of lumber supply is China. Japan has a geographical advantage in trading with China and there is already fair amount of container traffic in between the two countries,” he noted.

He hopes to launch a new era in Japan’s long history of lumber and planted forests.

“I want to create an era in which people in the world find various ways to use sugi and hinoki, appreciate their values and pay what they are worth. Considering the shortage of resources the world is facing, I believe that the lumber we have available in Japan comes as an attractive and valuable resource,” he said.

It costs money and effort to maintain forests, and without adequate profit there won’t be enough human resources in the sector or owners who are willing to take good care of their forests.

According to the Forestry Agency, about 65% of the planted forest land in Japan is privately owned. The health of these forests depends on the owners’ will to maintain them, but Yamada pointed out that many owners are getting too old to do the work required or are young inheritors who are not that interested in what they own.

Unless the owners are conscientious individuals who are aware of the environmental significance of these assets, the global challenges created by lumber shortages and the economic value of lumber, it will make no sense for them to maintain them either with their own hands or by outsourcing the work if they don’t feel it’s worthwhile.

The healthy cycle of maintaining planted forests is based on the healthy economic cycle of generating economic value by utilizing trees as a resource and using part of the profit to regenerate them.

“Maintaining forests is not as hard as you may think,” said Yamada, who is also an owner. “You just need to go and check your forest once a year or so, thin the forest if you think the trees are too crowded and cut vines if there are too many of them tangling on the trees and so on,” he said.

Protecting this centuries-long cycle of producing and nurturing high-quality lumber will keep the forests healthy while helping to preserve natural forests around the world amid growing demand for timber.

This article is sponsored by the Japan Wood-Products Export Association.

For more information, go to their website at https://www.j-wood.org/en/

Download the PDFs of this article