On the Pacific coast of Honshu, just northeast of the capital, is Ibaraki Prefecture — Tokyo’s secluded back garden. Home to the world-class technology hub of Tsukuba Science City and the developing industrial areas of Hitachi and Kashima, this fertile prefecture has always been enthusiastic about feeding new ideas, new investment, and the nation’s future.

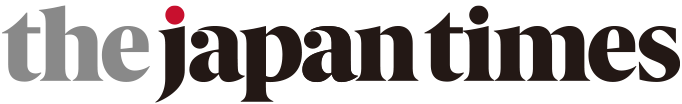

Given its flat landscape and mild climate, Ibaraki is not only a popular cycling destination but one of the nation’s leading producers of agriculture. Ibaraki grows more melons, chestnuts, lotus root and green peppers than any other prefecture and is also the source of popular livestock products, including Hitachi beef (a variety of wagyu), Hitachi no Kagayaki pork and Okukuji shamo (gamecock), which are gaining popularity.

Ibaraki’s long history is closely entwined with one of the most important clans in Japanese history — the Tokugawas. Based in Mito, the prefectural capital, lord Tokugawa Nariaki played an influential role in shaping the destiny of both Ibaraki and Japan. By imbuing philosophy, ritual, long-term planning and military thinking into his plans to protect Japan’s borders during its reopening, he helped reinvigorate national morale and laid some of the foundations for the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when imperial rule was restored under the emperor and the samurai lost their privileged status.

As host of this year’s G7 Interior and Security Ministers’ Meeting, Mito is an ever-evolving city famous for its scenery and fascinating cultural heritage. “Suifu” — another name for Mito — means “the imaginary city where the water gods live,” with the Naka, Hinuma and Sakasa rivers all flowing through it. The close proximity of the Pacific Ocean, along with nearby Lake Senba, means these waterways bring beauty and commerce to the city and play a strong role in the city’s identity.

Strategic pairing

Kairakuen is the city’s heart and soul, housing 3,000 plum trees of over 100 varieties. The garden is one of the “three great gardens” of Japan. When the plum trees are in bloom, every year from mid-February to the end of March, the garden attracts large crowds to view the flowers. The large grove of plum trees provides not only a stunning view, but also an insight to the minds of the planners: Kairakuen was designed with military defense in mind. The plum trees would also produce fruit that would help sustain a defending army and the bamboo was selected for its suitability in making archery bows. The plum blossoms bloom ahead of the spring even when there is still snow on the ground. It is believed that Nariaki chose plum trees because it reflected his desire to have his domain be the leader of the country.

Kairakuen is worth a visit any time of the year and unlike many of Japan’s traditional gardens, Kairakuen has always been open to all members of the public, not only the nobility. The garden has an expansive bamboo forest, Lake Senba and Tokugawa’s villa, Kobuntei, which features delicately painted wall screens and views of the gardens and surrounding wonderful scenery.

Nearby Kodokan holds an important place in Mito’s history. Kodokan was established as an educational facility to build the mind while Kairakuen was built as its companion establishment to give the people a place to relax and feed the spirit. Designated as a National Historic Site in 1952, the buildings are within the grounds of the ruins of Mito Castle. It was established in 1841 by Tokugawa to educate samurai and retainers of his clan. With a forward-looking curriculum, Kodokan played an important role in the intellectual and cultural development of Japan, developing a number of students who went on to become important figures in Japan’s modernization.

The two places form a partnership, as Tokugawa envisioned the people of his domain having somewhere to spend their time studying and somewhere to spend time relaxing. Much like muscles tense and relax, the concept was to provide a well-rounded lifestyle for the rhythm of his citizens’ lives. Interestingly, the school was built first by design, as there were concerns that should the park come first, students might become used to playing and become lax in their studies.

This was part of his vision combining traditional ritual and emerging technology to keep Japan independent as it emerged from the period of isolation launched in the early 1600s by the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu to prevent colonial and religious influences from affecting Japan. It would take until 1853 with the arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships for Japan’s reintegration to start, and for Tokugawa Nariaki to strive to steer Japan toward equality with the powers of the day. Kodokan had no graduations, with students able to continue studying even as they began their working lives — a concept not dissimilar to modern day post-graduate education. With its departure from traditional norms, Kodokan was in many ways a forerunner to Japan’s modern educational institutions.

Mito Tobukan is a martial arts dojo that values universality. Established in 1874, Tobukan inherited the motto of Kodokan: “The literary and the military are the same path.” Kendo, naginata (a bladed pole weapon) and iaido (sword drawing and cutting) are all taught here, and visiting practitioners are welcome to join training sessions.

Another martial arts landmark in the area in neighboring Kasama is Aiki Shrine, the world’s only shrine dedicated to aikido. Built in 1944 by Morihei Ueshiba, the father of aikido, the shrine is a sacred place to practitioners of the martial art.

Farming powerhouse

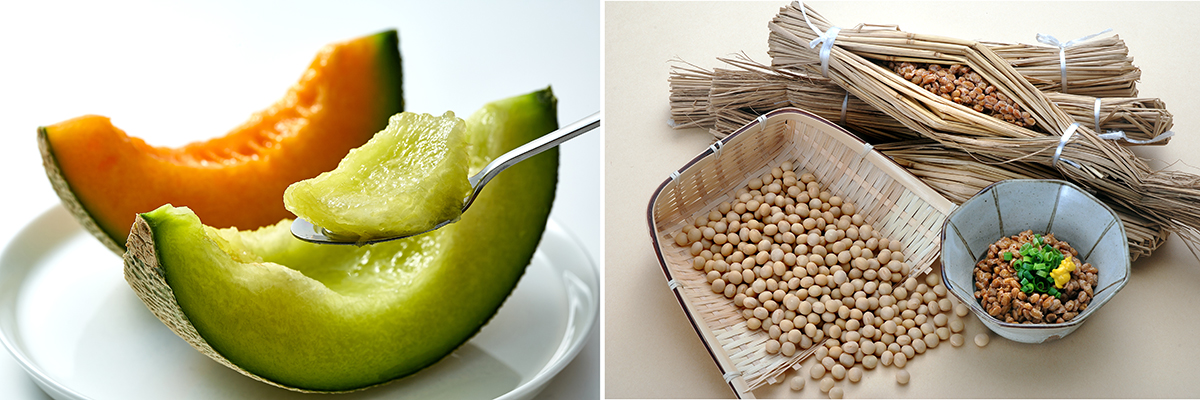

Ibaraki is a leading agricultural prefecture known for its sake and natto (fermented soybeans). The fertile soil and mountain-fed rivers provide ideal conditions for producing sake, and the prefecture has one of the largest number of breweries in the Kanto region.

Natto is perhaps Ibaraki’s most well-known product. Legend has it that a famous samurai, Minamoto no Yoshiie, was passing through Mito in 1083 when his troops were resting. In their haste, the troops hurriedly packed some freshly cooked soybeans intended for horse fodder, in sacks made of rice straw. Forgotten for several days, bacteria from the straw combined with the warmth of the horse carrying the sacks caused fermentation, creating a sticky, pungent food that the troops (not the horses) ate, and a legend was born. Natto is now eaten daily as part of breakfast and other meals all over Japan. The actual origins are likely more prosaic, as the ingredients and tools needed to make natto have been available in Japan since ancient times. Today, the benefits of fermented foods are well documented and soybeans are an excellent source of nutrition, giving natto a deserved reputation as a health food.

Enchanting lanterns

Lantern-making is a traditional Japanese art and Mito is one of three major production centers in Japan. After starting about 380 years ago, production of Suifu lanterns still goes on in Mito in both traditional and modern designs. Suifu lanterns are made with a type of water-resistant Japanese paper and locally grown bamboo, making them both durable and practical. Craftsmanship of such lanterns is still in demand today, a cultural legacy that visitors can try at some of the local workshops.

The paper, made in Nishinouchi, where Kozo mulberry plants grow, is an Ibaraki speciality and is as sturdy as textiles. Nishinouchi paper is used in making lanterns, sliding doors and calligraphy, but the most unusual historical usage was in accounting. The water-resistant paper could be thrown into wells in the event of a fire, protecting important documentation even when wet.

The people of Ibaraki are happy to invite everyone to share their rich bounty of flowers, nature, food and culture and discover all the charms their prefecture has to offer in all four seasons.

This page is sponsored by the Ibaraki Prefectural Government.