The eighth Tokyo International Conference on African Development will be held in Tunisia from Aug. 27 to 28. Since 1993, the Japanese government has been leading this conference, which is hosted with the United Nations, the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank and the African Union Commission.

TICAD is unique in that its main agenda is not limited to investment and trade, but also incorporates various social and political issues facing Africa. Along with financial assistance, Japan has been providing grassroots support, and measures to combat COVID-19 are a significant part of these efforts.

Popular Japanese entertainer Pikotaro, who was appointed by the Foreign Ministry in 2017 to be a goodwill ambassador for promoting the U.N. sustainable development goals (SDGs), released a hand-washing video titled “PPAP-2020” during the pandemic in 2020. It went on to become a worldwide hit and has been used by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to support health and hygiene education in Zambia as part of efforts to fight COVID-19 there.

Raising awareness of SDGs

That hand-washing video was based on his novelty video “Pen-Pineapple-Apple-Pen,” abbreviated as “PPAP,” which went viral on YouTube in 2016, bringing him global recognition. It subsequently went on to be recognized by the Guinness Book of Records as the shortest song to enter the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Pikotaro’s work as an SDGs ambassador involved performances at state functions, including a reception hosted by the Japanese government at U.N. Headquarters in New York in 2017.

“I thought that the first step was to have people understand what the SDGs are,” Pikotaro said. There are 17 goals, ranging from “no poverty” to “partnerships for the goals,” but Pikotaro thinks many people tend to associate the SDGs with environmental issues.

Inspired by the positive reaction the original “PPAP” video drew from children, he is particularly interested in the fourth goal — quality education. “PPAP-2020” was created as something that would be easily accessible and enjoyable for children around the world, regardless of country, culture or language.

Pikotaro points out that the early days of the pandemic were difficult, with people being told to stay home and daily activities severely limited. Thinking about what he could do as an entertainer, Pikotaro hit upon the simple idea of encouraging young children to wash their hands.

Connecting with a smile

“At that time, I felt that all the measures against COVID-19 were very serious, and I wanted to come up with something lighthearted,” he said. “If it isn’t fun, children won’t respond to it. Rather than talking to children about viruses or vaccinations, having clean hands is a very basic first step they can take.”

Using the familiar tune and choreography from “PPAP,” the 2020 version has Pikotaro repeatedly singing “wash” in a heavy Japanese accent while playfully demonstrating the health ministry’s rigorous hand-washing procedure.

“PPAP-2020” was conceived and completed at home in just five days. After Pikotaro released it on YouTube in April 2020, the video received over 10 million views in about a month, reaching more than 150 countries around the world.

One of the core philosophies that inspire Pikotaro is world peace. Tapping into the wide recognition garnered by the original “PPAP” video, he came up with “Pray for People and Peace” as the catchphrase behind the 2020 version. “When it comes down to ‘What is peace?’ I really believe it means having an environment where people can sing, dance and enjoy entertainment.”

Inspiration in Zambia

“The original ‘PAPP’ was very popular in Africa,” Pikotaro recalled. “Then very soon after the release of ‘PPAP-2020,’ JICA approached me about using the new video for their efforts in Zambia.”

More than 6,000 Zambian children from shantytowns in Lusaka, where many homes don’t have sufficient water infrastructure, participated in some 120 sessions for the hand-washing campaign, which included a basic classroom lecture on COVID-19 and a well-known Zambian comedian performing “PPAP-2020.”

The rhythm, actions and simple lyrics were easily understood even by children who did not yet understand English. Follow-up interviews with families of the participants revealed a heightened awareness of the importance of hand-washing and positive feedback from the parents.

While Pikotaro visited Uganda when he was appointed tourism ambassador in 2017, he hasn’t yet been to Zambia. He says he would really like to go.

“I’m interested in finding out more about issues surrounding water and sanitation. For example, it would be great if there was some way to use Japanese expertise in terms of technology and infrastructure to provide clean water for everyone. Everything in our lives starts with water, after all,” Pikotaro said.

Health care for all

The COVID-19 vaccination rate in Africa is rising but is still low compared with developed countries. Vaccination remains focused on adults over 18, and only 7% of doses administered in 23 countries were given to children and adolescents. The median coverage among adults over 18 who completed their primary series is 34%.

Since June 2020, Japan has been providing support for new COVID-19 infection controls in many African countries through bilateral and international organizations. Japan has long positioned the health sector as a priority area for TICAD, and continues efforts to build resilient and inclusive health and medical systems. This includes the promotion of universal health coverage — a term that means all individuals and communities are receiving the health services they need without suffering financial hardship.

Having built its own national health care system, Japan is using that experience to promote international cooperation on achieving UHC based on the principle of “leaving no one’s health behind” in the global fight against COVID-19. Japan’s support for COVID-19 countermeasures in Africa includes the provision of medical supplies, equipment and technical cooperation, help with developing human resources, and contributions of $1 billion to the vaccine distribution program COVAX and additional pledges of up to $500 million for future efforts.

Building on a legacy in Ghana

Japan established the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research in Ghana as a core research center for Ghana and its neighbors, and has been providing technical cooperation and grant aid for the past 50 years.

The institute has been conducting about 20,000 PCR tests per week, accounting for 80% of all COVID-19 testing in Ghana. The center is named in honor of Japan’s Hideyo Noguchi (1876 to 1928), a doctor who dedicated himself to the study of infectious diseases around the world, including Africa.

The strong bond between Japan and Africa is also manifested by the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize, an award that recognizes medical research and medical services in Africa and honors change-makers — both individuals and organizations — at the forefront of efforts to combat disease and improve lives. The awards ceremony for winners of the fourth Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize will be held in Tunisia during TICAD 8.

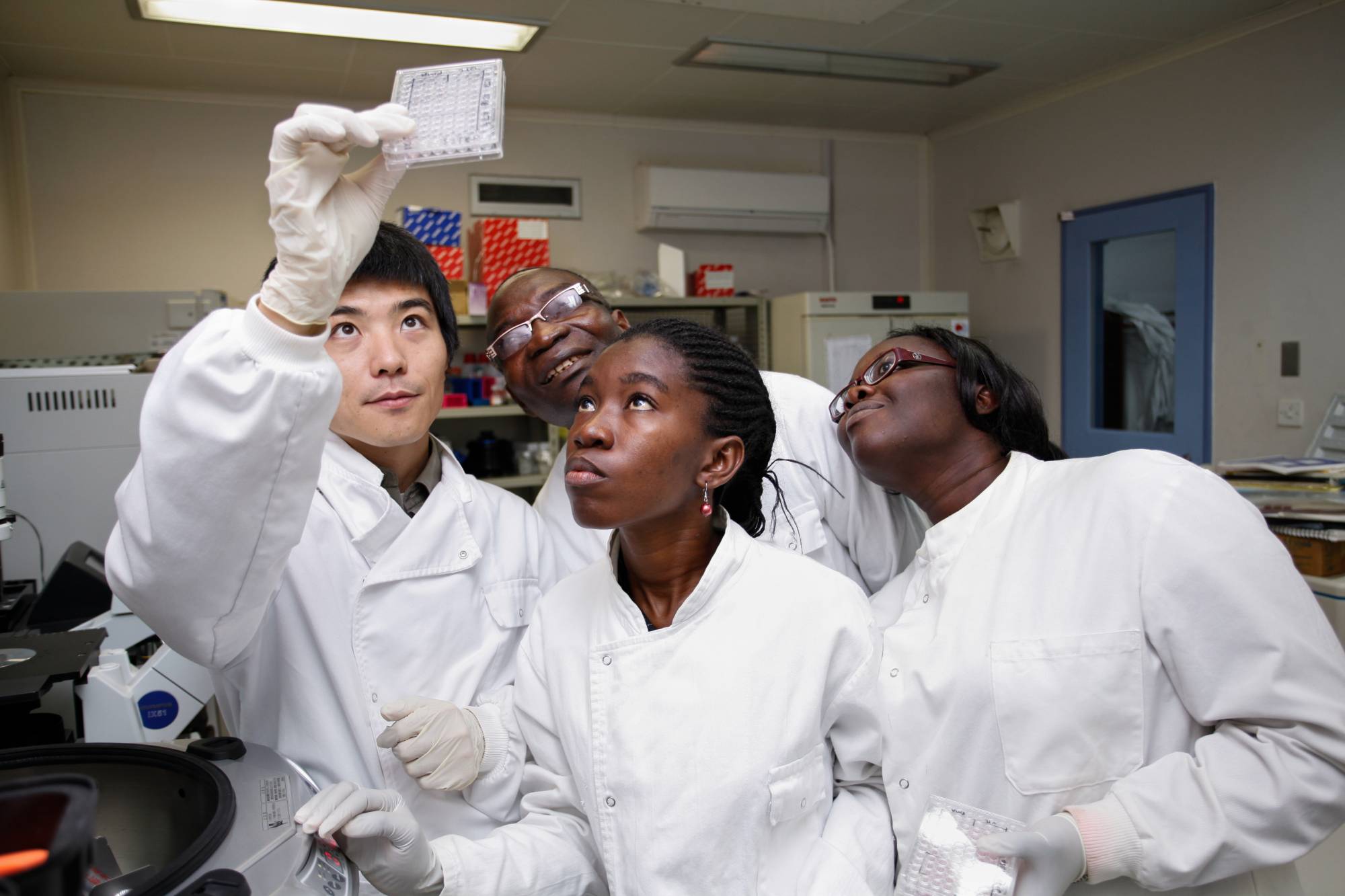

Initiative offers African youth valuable skills

As part of Japan’s efforts to enhance relations with African nations, the African Business Education Initiative for Youth, run by the Japanese government and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, has provided opportunities for more than 1,500 people from 54 countries to pursue master’s degrees at Japanese universities and experience internships at Japanese companies.

The ABE Initiative was announced by the Japanese government at the fifth Tokyo International Conference on African Development in 2013. With the International Labour Organization noting that youths in Africa were facing labor issues such as unemployment and unequal opportunities, the Japanese government — recognizing that stable development of industry and business in Africa would benefit not only the continent, but also the world — created the ABE Initiative.

Gaining new perspectives

Zanele Phiri from the Kingdom of Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland) participated in the ABE Initiative from 2019 to 2021. In addition to studying at the Graduate School of International Management of the International University of Japan in Minamiuonuma, Niigata Prefecture, she participated in an internship program at a rice and strawberry farm. She was also able to take part in short-term intensive entrepreneurship training provided by JICA.

Her achievements to date and her ongoing journey to make a difference in her society are a perfect embodiment of the aims of the ABE Initiative, as she works to develop African industries and be a potential “navigator” for Japanese firms operating in Africa.

After earning a degree in agriculture at the University of Eswatini, Phiri started working at Southern Africa Nazarene University. But she also had a desire to study business. Unfortunately, many of the business management courses she found in Africa were too expensive. After hearing about the ABE Initiative from her supervisor, she jumped at the opportunity and immediately applied.

In Niigata, she studied mainly Japanese agriculture policies and business development, spending time between and after classes visiting rice fields and vegetable farms near the IUJ campus. From interacting with area farmers, she learned that Japanese agriculture is similar to that in her own country, where many farms are relatively small and run by families or small and midsize enterprises. Based on these similarities, Phiri said, “Eswatini can learn from Japan on how to manage supply and demand of their main staple of rice, and apply it to white maize, Eswatini’s main staple.” She also noted that learning how Japan systematically implemented policies to improve productivity and support farmers, protect their land rights and put in place water infrastructure for agricultural use would help Eswatini improve its self-sufficiency in maize.

Phiri said there were many values and perspectives that inspired her through her interactions with local farmers and companies. “There was a lot to learn from the way of life of the Japanese people — the way they exhibit a strong work ethic, respect and empathy for others and respect for nature,” she said. She was also impressed to learn that many companies, even small and midsize enterprises, incorporate the ideas of the U.N. sustainable development goals (SDGs) in their business practices.

Transferring solutions

Another novel perspective she thought could be applied to local businesses in Eswatini is the idea of turning environmental disadvantages into something useful.

“For example, Minamiuonuma has a lot of snow in winter. But instead of saying that there is not much they can do in the winter, they use the snow and cold weather for various things such as storing products that taste better cooled or preserved,” Phiri said. She felt that this kind of thinking could turn local factors, including those that may seem like disadvantages, into new values that could contribute to the branding of local products.

“What is not happening in Eswatini is the implementation of an effective strategy to promote local brands. A combination of innovation, passion for the local community and strong leadership is important to develop and promote local brands. This was something I could see in how Minamiuonuma’s Koshihikari rice is promoted across the nation,” she said.

Phiri said the JICA entrepreneurship program is useful for her and other young Africans with entrepreneurial aspirations. “It helped me to think more about my business concept and redefine my business model based on which of the SDGs are achievable and whose problems it can solve,” she said.

Another benefit of the program is that it helped her connect with ABE Initiative participants across Japan. “Because of this opportunity, we were able to meet like-minded people and learn about each other’s businesses and innovative ideas. It’s nice that we continue to communicate online,” she said.

Using everything she gained in Japan, Phiri has been working practically nonstop since returning to Eswatini in June 2021.

“The moment I came back home, I launched my own start-up called Makwandze Organica, an agribusiness focusing on growing organic vegetables in a sustainable way and promoting farmers’ brands in my local community,” she said, explaining that makwandze means “I’m wishing you fruitfulness and prosperity.” The phrase is interchangeable with thank you. On her farm, she grows indigenous vegetables, a variety of spinach and lettuce as well as strawberries, which she learned how to grow during her internship in Japan. “I keep in touch with the company.... They give me advice and we are talking about the possibility of doing something together in the future.”

Changing mindsets

She also began work to get her government involved in identifying and promoting local products, while addressing social problems at the same time.

“For example, we have several tourist spots in our community, including the biggest dam in Eswatini. I want to engage farmers and the government in an agritourism project, for which I applied for a grant from the United Nations Development Programme,” Phiri said. Through this project, she believes that she can promote the area, bring in more tourists and create more jobs while contributing to improving food self-sufficiency.

Upon her return to Southern Africa Nazarene University, Phiri was reinstated to her former position as head of the Department of Business Management and Entrepreneurship. In addition to teaching, she is part of the university’s curriculum development committee. She thinks the fastest way to effect change in society is to raise people’s awareness through education and convince them that their actions matter.

“I could have not done all of this without the knowledge and experience I gained from IUJ, the JICA entrepreneurship program and my internship in Japan,” she said. Now Phiri is more innovative in her business practices and more conscious of achieving the SDGs through her business and academic activities.

She encouraged young people in Africa to study in Japan.

“There are many things that developing countries can learn from Japan. You should have clear professional and personal goals on what you want to achieve when you return to your country and try to learn beyond the classroom by taking advantage of opportunities such as the JICA entrepreneurship program and internship program.”

The Japanese government will continue supporting human resource development in Africa in various fields such as industry, agriculture and health and medical, as well as strongly push for development that is led by African ownership.

This page is sponsored by the government of Japan.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.