In 2009, UNESCO in its “Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger” designated the Ainu language as being critically endangered. As the most dire of the five categories — only extinct is worse — used in the report, it highlighted the precarious state that had befallen the language.

Still, over the years before and since, a variety of initiatives have been undertaken to revitalize Ainu by stirring interest in it through pop culture, scholarship, the internet and other avenues.

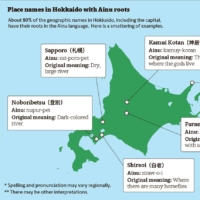

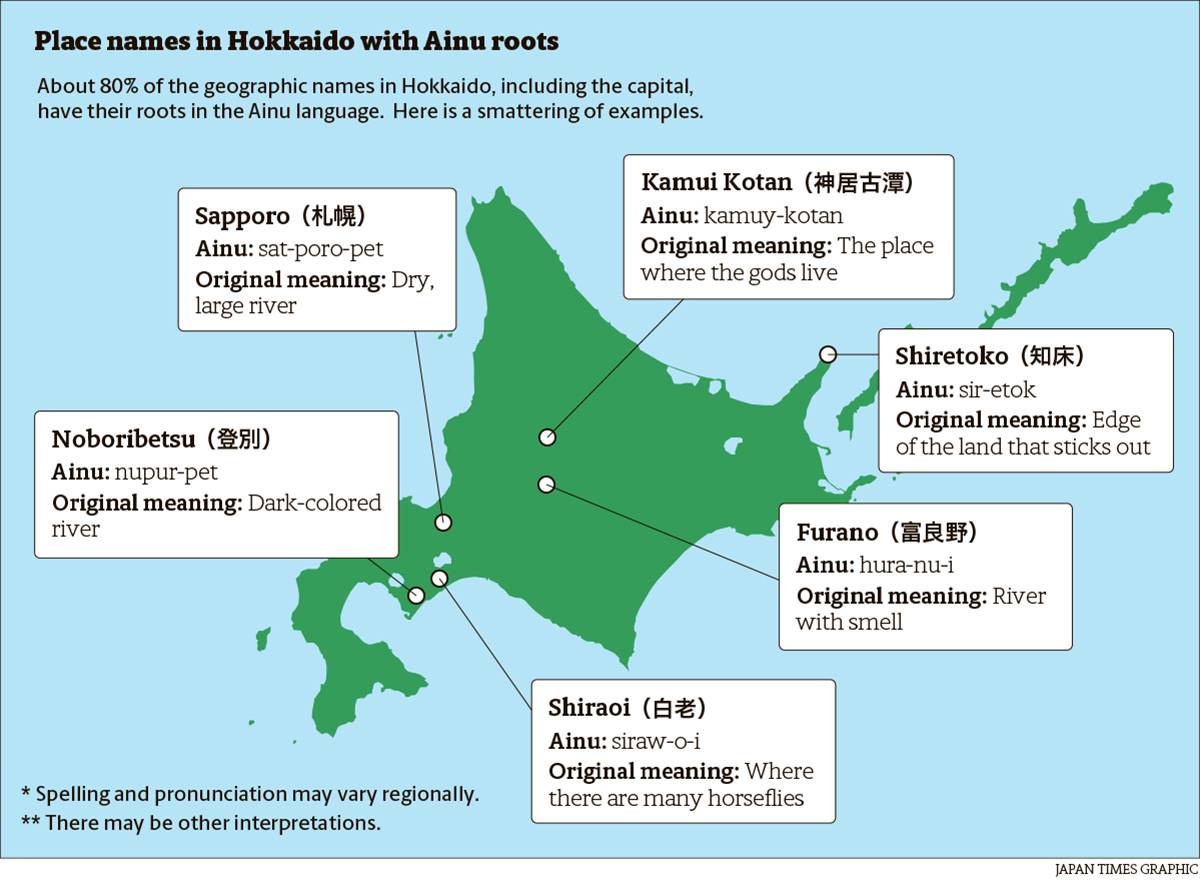

An oral language that did not have its own writing system, Ainu has been brought to the brink through the process of assimilating its speakers, most prominently the indigenous inhabitants of Hokkaido, into Japanese society.

This process began in earnest during the Meiji Restoration in the late 1860s, when the new government began to exercise direct control of the island and wajin (a historical term referring to the ethnic Japanese, or non-Ainu people) began to settle there in large numbers.

Ainu people were taught Japanese in schools built by the newcomers. Their minority status and the economic realities of needing to do business with the newcomers in their language led many in the indigenous population to abandon their traditions and not teach their native language to their children.

A unique language claws back

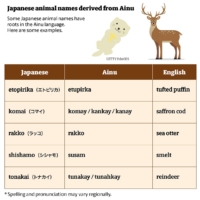

The Ainu language, it should be noted, is an isolate, meaning it is not a dialect of Japanese, for example. It has no linguistic connection to Japanese or, for that matter, to any other East Asian language.

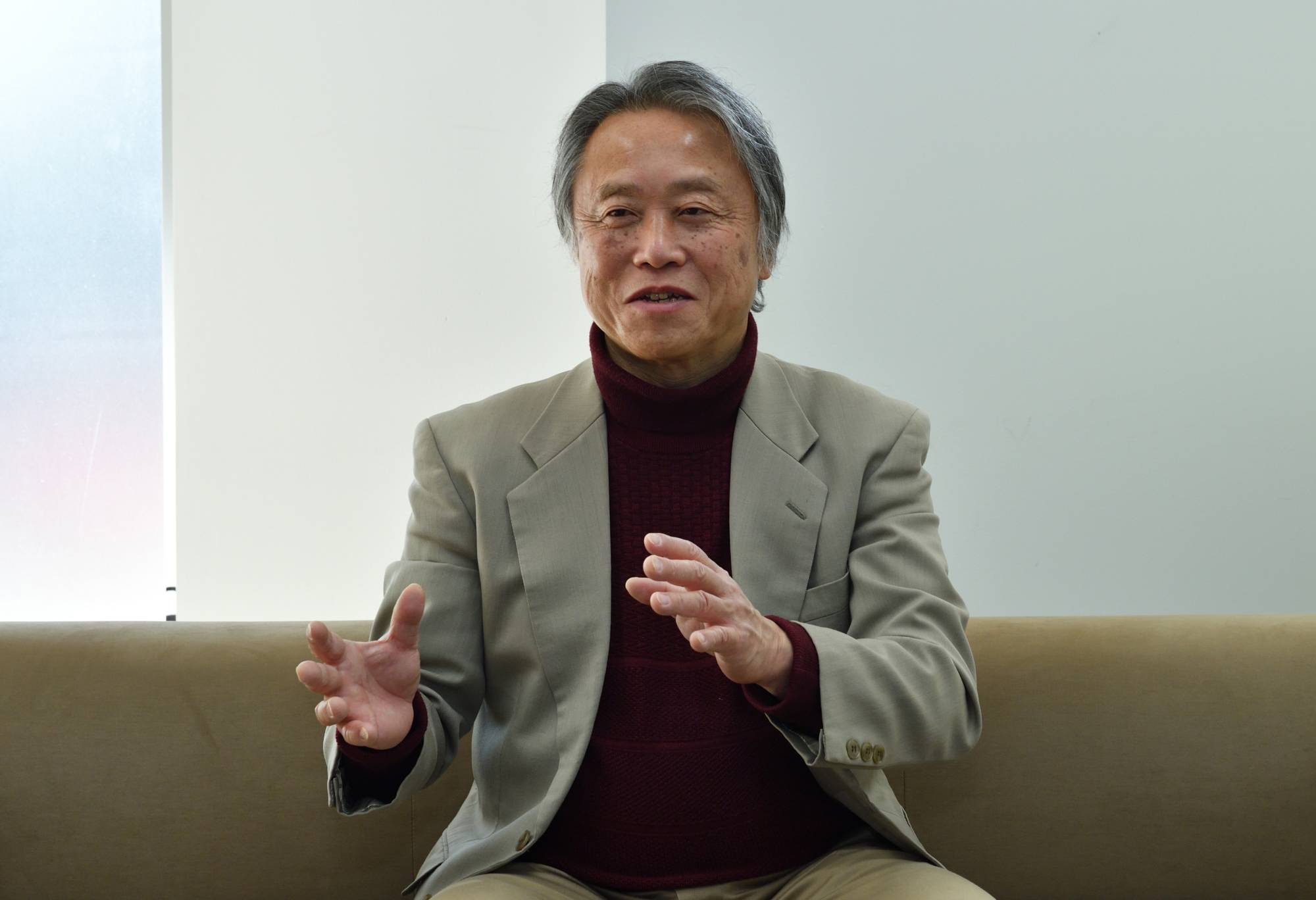

“The fact is, Ainu is not the only language in the region that can be defined as an isolate. Japanese and Korean are also isolates,” explained Hiroshi Nakagawa, a Chiba University professor emeritus of linguistics and Ainu culture. “In fact, if you look around Northeast Asia as a whole, there are numerous minority group languages throughout the region that are linguistically isolated. Ainu is one of them. Sure, we can still point to grammatical similarities among Japanese, Korean, Mongol and some other languages, but here, too, Ainu still stands alone.”

And when it comes to speakers of the language, the current situation is even more concerning than UNESCO suggests, Nakagawa warned.

“UNESCO said a few years ago that there are still 15 native speakers of Ainu, but we observers simply do not think that is the case,” he said. “Today, there is no one who speaks only Ainu, and there is no one who can speak Ainu better than they can speak Japanese.”

For his own part, Nakagawa’s own interest in Ainu as someone from outside the community arose from a simple desire to research a non-European tongue. However, something an elderly Ainu speaker said one day makes him wonder if some other force might have been at work.

“One of these older ladies who’d been teaching me Ainu terms looked at me and said, ‘I can see your tsukigami (guardian spirit),’” he related with a twinkle in his eye that shined through even over a video call. “‘And I can see that your tsukigami wants you to learn Ainu.’”

Regardless, whether out of a simple desire to beat his own path or due to having acted under the impetus of powers beyond human ken, Nakagawa now numbers among the scholars and activists, as well as people in the arts, business and government, who remain determined to keep the language and culture alive, not just today, but for tomorrow as well. Their efforts across the spectrum may already be having some impact.

“While we don’t have exact statistics, my sense is that the number of people who can speak Ainu to at least some degree — especially young people — is sharply on the rise,” Nakagawa noted. “Increasing the number of people who speak Ainu as a native language is necessary as a remote objective, but what’s crucial as a realistic objective is increasing the numbers of those who study in connection with their own ethnic identity.”

Pop culture solicits savior

Interestingly, thanks to manga writer Satoru Noda, the academic Nakagawa even found himself playing a role he perhaps never expected: Since 2014, he has served as the Ainu-language supervisor on Noda’s popular comic book series, “Golden Kamuy.”

Set in the early 20th century, the adventure series features a young Russo-Japanese War veteran with an Ainu girl on a quest for gold stolen from the Ainu. The full details of the adventure tale are far too complex to be related here; however, aside from the story itself, what seems to make the series compelling for many is the fact that it also offers a rich portrayal of Ainu culture.

Nakagawa’s role as the Ainu language expert for the series came about through the Ainu Association of Hokkaido.

“The association first connected me with Noda,” Nakagawa said. “The manga was set to begin life as a magazine serial, and he had prepared a few segments before I came on board.”

“When we first spoke, he told me what his plans were for the series and what he was looking for,” he continued. “I read what he had prepared and thought, ‘Oh, this is really interesting.’ The content is wonderful. The depictions of the Ainu in particular were amazing. I told him that he should feel free to ask and I would lend a hand. This is how my involvement began.”

Nakagawa’s chief role has been to offer detailed advice related to Ainu terms and language, though he occasionally offered suggestions about characters and situations. “Essentially,” he explained, “I answer whatever questions Noda has” about Ainu culture and language.

The manga certainly seems to have struck a chord in Japan. Aside from sales of the original magazines, some 18 million copies of the 28-volume series in book form have been sold so far. Among other awards, it took the Manga Grand Prize in the 2018 edition of the prestigious Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize.

Interestingly, “Golden Kamuy” also seems to have captured the imaginations of some abroad. It has been republished in translation overseas, and images from the manga were even featured prominently as the key visual for a 2019 British Museum exhibition of manga art.

Adding to its impact, the comic books have also been turned into a popular animation series of the same name.

Such mainstream popularity is surely helping to keep interest in Ainu culture and language alive today among the general public. In addition, Nakagawa has seen sales of a work he subsequently produced to explain the culture more deeply via the comic book series — “Ainu Bunka de Yomitoku Golden Kamuy” (“A Deep Read of Golden Kamuy Through Ainu Culture”) — post strong results as well, offering perhaps further proof the manga has helped to increase interest in Ainu culture.

But perhaps even more important than the mainstream reaction, he added, has been the response from the Ainu community.

“On the whole, people in the Ainu community have been pleased about the series,” he said. “Whenever Ainu have been presented in films and so forth in a historical context, in most cases they have been shown in a pitiful light. Their culture is referred to as being on the verge of extinction and so forth.”

“Previous works also have fantastical elements,” he added. “However, this story does realistically present Ainu within an historical context. Moreover, it shows them not as being weak victims, but rather as a people actively trying to control their own destinies. This kind of presentation has been a first for the community. They’ve been waiting for someone to tell a story like this.”

This is not to say that the manga (or anime) have been universally well-received within the Ainu community; for example, depictions seen as exaggerated and perhaps grotesque by some have been brought up as causes for objection.

Taking it to the next level

Still, if nothing else, the series does offer the possibility of reaching out to both the Ainu community and the general public to stoke interest in Ainu culture. In addition to pop culture, Nakagawa and his research peers are engaged in other activities that help to fill in the gaps. For example, he is part of a multinational team that has created a glossed audio corpus of Ainu folklore for the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. At this website, visitors can hear recitations of Ainu folk tales accompanied by written glosses of the Ainu being spoken and sentence-by-sentence translations in both Japanese and English.

Materials are also being created that should appeal to more than just scholars. Chiba University’s Center for Areal Studies currently hosts a website for children that uses games through which they can learn some basic Ainu vocabulary and cultural concepts while they play. Nakagawa has also published introductory Ainu-language texts and volumes on Ainu folklore.

The ultimate hope for all these works has been to spark interest in Ainu language and culture and help keep them alive. However, interest in some relatively exotic culture alone is not enough.

“Economics are the basic reason why minority languages disappear,” Nakagawa observed. “People stopped using Ainu because they couldn’t get by if they couldn’t use Japanese,” he went on, stressing the need for linkages to be formed between economic activities and Ainu culture.

Still, the basic interest in keeping Ainu alive is there, as evidenced by the responses to “Golden Kamuy” and the like. For example, as Nakagawa pointed out, there has been the positive development of an uptick in the number of television programs that cover Ainu topics.

Things like “Golden Kamuy” are first steps, Nakagawa said, and the issue now for those people seeking to revitalize Ainu language and culture is how to take the interest that has been created to the next level.

“The situation that I think we should be aiming for is one in which the Ainu language and culture are allowed to develop in a way that does not seem to be out of place. Hearing Ainu spoken in the course of everyday life should not seem like something exotic. Hopefully, something like ‘Golden Kamuy’ can contribute in some way in this regard.”

This page is sponsored by the government of Japan.