The world is facing a new nutrition reality where persistent undernutrition and escalating overnutrition coexist even within individual populations. This double burden of malnutrition imposes a set of new challenges for policy and program development. With less than five years left to achieve the World Health Assembly’s targets for maternal, infant and young child nutrition, and 10 years to reach the U.N. sustainable development goals (SDGs), the third Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit will be held in Tokyo from Tuesday to Wednesday.

The summit aims to foster a common understanding of key actions to improve nutrition worldwide and provide a forum for discussions under five themes: integrating nutrition with universal health coverage; building food systems; promoting resilience; promoting data-driven accountability; and ensuring financing for nutrition. Diverse stakeholders, including governments, international organizations, the private sector and society, will be encouraged to review their policies, measures and strategies and present new funding plans or policy commitments to accelerate the implementation of their initiatives.

As the host and a country with one of the highest life expectancies, Japan is ready to share its expertise accumulated over more than 100 years. A rich history of this nation’s dedication to nutrition improvement can provide useful insights into how the world can bring an end to long-standing nutrition-related issues and achieve a brighter, more prosperous future for all.

Origin of commitment

Japan’s nutrition-related initiative dates back to the late 19th century, when the country started its new life as a modern nation. To tackle nutritional deficiencies caused by food insecurity, Dr. Tadasu Saiki established the world’s first nutrition research institute privately in 1914, which was relaunched in 1920 as the National Institute of Nutrition, predecessor to the National Institute of Health and Nutrition (NIHN). The institute invested substantial resources in collecting and analyzing data, such as the nutrient composition of major food items and the dietary intake per capita as determined from household surveys, accumulating a large volume of scientifically valuable data. This allowed the government to gain insights into the public’s nutritional status and take appropriate measures, paving the way for the national nutrition policy of “leave no one behind.”

After World War II, with assistance from abroad, Japan overcame nutritional deficiencies in a remarkably short time through various nationwide activities led by nutritional specialists. Of particular note is the annual nutrition survey that began in 1945. According to Dr. Hidemi Takimoto, chief of the Department of Nutritional Epidemiology and Shokuiku at the NIHN, this survey originally targeted Tokyo residents and was later conducted nationwide. “Even during the difficult times after the war, the government was aware of the importance of monitoring people’s nutritional status in developing nutrition policy,” Takimoto said. Except for 2020 and 2021, when the survey was suspended due to the coronavirus pandemic, this survey has been conducted annually for over 75 years, helping Japan continuously advance its policy according to the changing needs of the times.

Japan is one of the rare countries to establish nationwide nutrition improvement programs ahead of its economic development. With the start of the overnutrition era, which coincided with Japan’s high economic growth spurt from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, the survey was expanded to include blood pressure measurements in response to the rise of new nutrition challenges, such as those posed by obesity and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

This forward-thinking policy allowed Japan to make substantial gains in life expectancy in tandem with the increase in the gross domestic product. In 1985, it reached the highest level of longevity in the world, with a healthier older population and lower obesity rates than other developed nations.

Japan’s nutrition policy

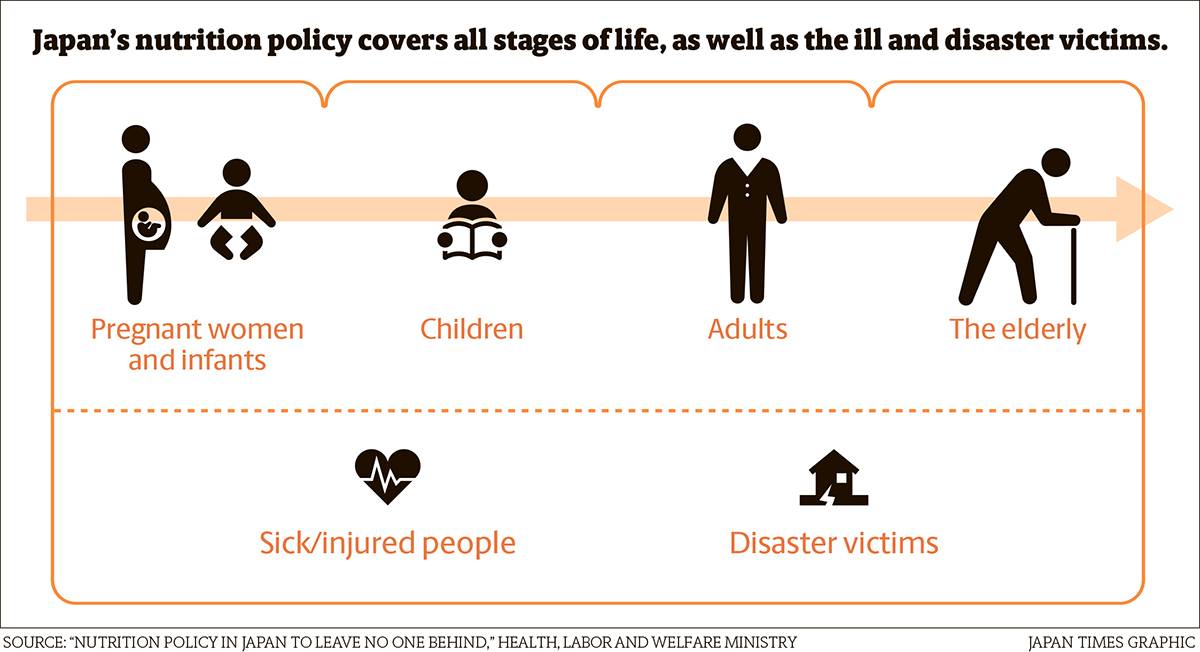

Japan’s health and nutrition policy consists of three main elements: educational activities based on diet; training and nationwide deployment of specialists; and a policymaking process based on scientific evidence. With these core elements, Japan has been promoting nutritional programs that cover people throughout their lives from infants to the elderly, as well as those who are sick, injured or victims of disaster.

The first element focuses on promoting diet or eating style. The traditional Japanese diet is characterized by ingredient diversity and meals that often consist of a staple food, a main dish and a side dish for ideal nutritional balance. Educating people to pay attention to the appropriate timing for meals, as well as the importance of communication and interaction at the table, is also essential.

Japanese learn firsthand about this concept from an early age through school lunch programs. By serving lunch to their classmates, they gain a visual understanding of appropriate portion size and how various dishes go together.

The second element, which affects a wider range of people, involves sending trained specialists and volunteers to manage nutrition at various facilities nationwide. These specialists also provide nutritional guidance to local communities to disseminate proper dietary knowledge and nutrition skills based on region-specific needs. Their activities play an important role in shokuiku, as food and nutrition education is called in Japan.

Food services provided at schools, company cafeterias and hospitals in Japan are carefully managed by registered dietitians (RDs) and other nutritional specialists, with close attention paid to balance. This system started about 100 years ago when Saiki envisioned a society with better nourishment for all. He established the Nutrition School in 1924 to train specialists to provide dietary guidance and manage food services to address nutritional deficiencies. Dietitian training was legislated by the Dietitians Act of 1947, which was partially revised in 1962 amid rising demand for more advanced dietary management to address the rising prevalence of NCDs, providing the foundation for the current registered dietitian system.

RDs and dietitians are active in various settings, including hospitals, schools and elder care facilities, to name just a few. Working closely with specialists in other fields, they tailor their approach to each site’s unique needs. Additionally, they provide dietary guidance to organizations, including businesses and medical institutes, and people whose lives have been disrupted by disaster. “Registered dietitians are nationally licensed nutritional specialists, and their role, together with the nationwide network of professional dietitians, characterizes Japan’s nutrition policy,” Takimoto explained. Their advanced skills and expertise are also contributing to developing dietitian systems in Vietnam and other countries.

The final element is a well-structured framework where scientific evidence feeds the government’s decision-making process. Under this framework, the government has formulated various health promotion initiatives at both the national and local levels to reduce health disparities across regions. One notable example is the Smart Life Project initiated in 2011 that aims to create a society in which everyone, including those who are not especially health-conscious, can be healthy. It encourages voluntary, effective health promotion activities throughout society, including the development of food products and menus for reducing sodium intake and increasing vegetable consumption.

In Japan, shokuiku has been promoted in cooperation with nutrition policy. The Basic Plan for the Promotion of Shokuiku has been redrawn every five years since 2006 to affirm the government’s commitment to promoting healthy dietary habits at home, school and within one’s community. The fourth plan began in March, with shokuiku positioned as part of Japan’s action plan to contribute to achieving sustainability in line with the SDGs. Taking into account the global context for nutrition issues, the plan calls for efforts to promote shokuiku with a focus on lifetime physical and mental health, sustainable food and nutrition and responses to the new normal and digitalization. In the next five years, the government will cooperate with various stakeholders to develop shokuiku further as a national campaign and achieve common goals.

These developments in Japan’s health and nutrition policy mean the country is entering a new phase and ready to extend its reach worldwide. Takimoto expressed her hopes for the upcoming N4G summit, saying “I see this summit as an opportunity to reaffirm the fact that nutrition is fundamental to good health and take action toward ensuring equal access to safe and nutritious food.” Takimoto will speak about child nutrition at one of the side events during N4G.

Global challenges

The pandemic has damaged food supply chains and delivered an economic blow to households, and the world can no longer afford to delay acting on the global challenge of malnutrition. One bright note, however, is that what the world is facing today is not new to Japan. With vast experience and knowledge accumulated through intensive research over more than a century, Japan believes it can offer a solution to global nutritional challenges and help achieve a caring and resilient society where no one will be left behind.

This page is sponsored by the government of Japan.

Download the PDFs of this Tokyo Nutrition for Growth Summit 2021

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.