It is not easy to grasp the big picture of water issues, which range from public health and environmental problems to socioeconomic challenges and technological solutions.

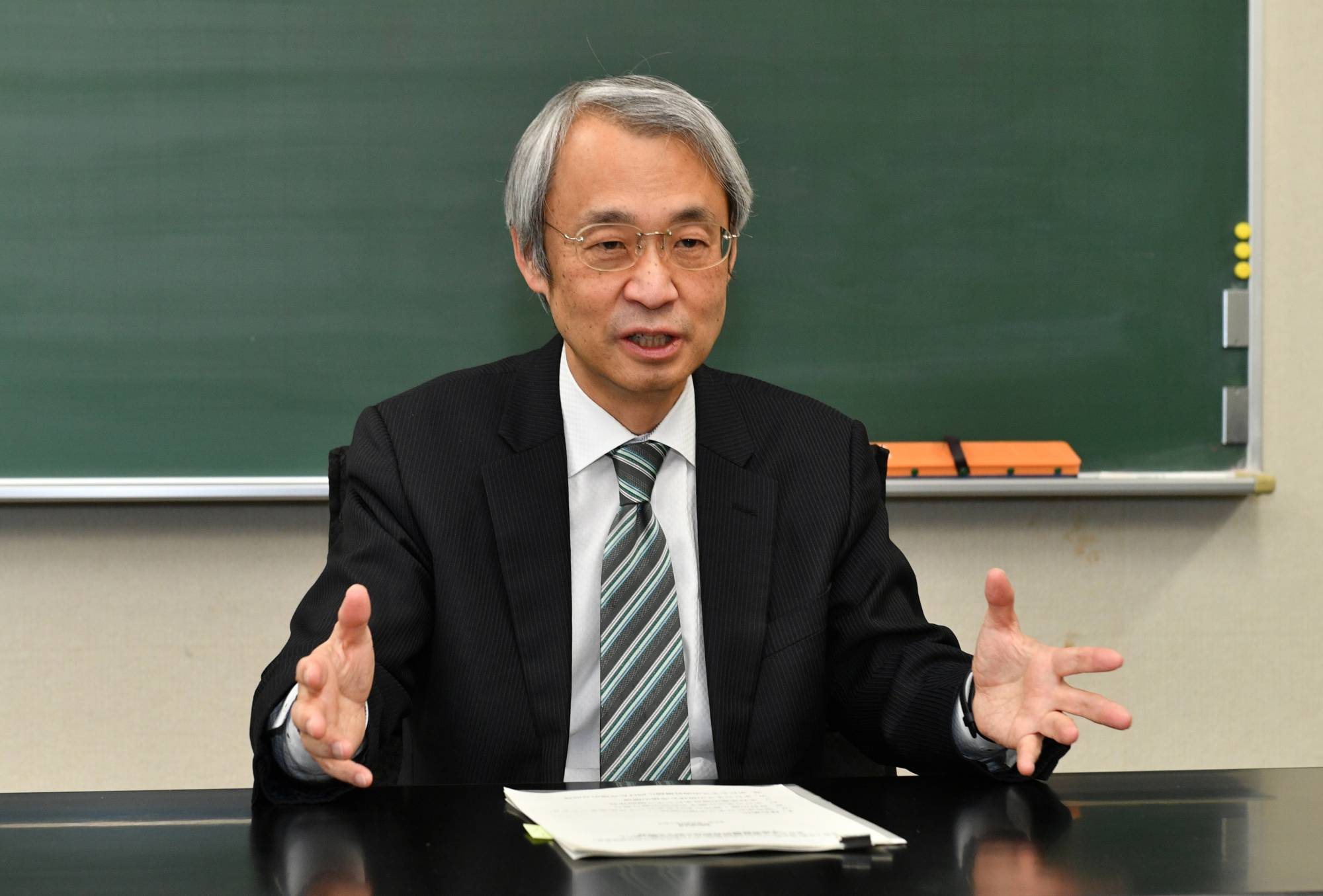

Professor Satoshi Takizawa, director of the Research Center for Water Environment Technology at the Graduate School of Engineering at the University of Tokyo, who also teaches at the university’s Department of Urban Engineering, has studied engineering and management of urban water systems in Japan and developing countries. He taught at the Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok from 1997 to 1999 and has participated in many international research projects.

Having served over a decade leading a panel on overseas expansion of the Japanese water industry for the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, professor Takizawa shared his thoughts on water with The Japan Times.

JT: What made you study urban water systems?

Takizawa: As a student in the 1980s, I became aware of water pollution in Japan and beyond, as well as diseases caused by unsafe water in developing countries. That led me to think of solutions making use of waterworks engineering rather than manufactured products. It’s been nearly 40 years.

JT: What are the major challenges?

Takizawa: Water is distributed unevenly across the Earth’s surface. The annual average rainfall in Japan is about 1,700 millimeters, while countries in the Middle East receive very little rainfall, less than 50 millimeters a year. There is no point of discussing the world average. That’s one of the difficult points regarding water resources.

Another challenge is water scarcity due to population growth. In particular, population growth and industrialization in urban areas are causing serious water shortages. How to manage urban water systems has become a major issue for the industry.

JT: Do you think businesses can contribute to solutions or should the challenges be basically addressed through official development assistance (ODA)?

Takizawa: Water is essential for life, but water issues have many aspects. On one hand, all people should be ensured access to safe water to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living. To address challenges in this field, Japan has built wells in rural areas of developing countries as part of its ODA. This is not business.

On the other hand, advanced urban water and sewerage systems should be supported by residents who benefit from them. And it’s natural that those who pay for such services demand that they be run economically and efficiently. That’s where we need to see the issue from a business point of view.

JT: How has the Japanese water industry been involved in projects overseas?

Takizawa: In Japan, operation and maintenance (O&M) of waterworks systems are basically handled by local governments. Some of them started supporting water projects in developing countries around 2000, as shown by Kitakyushu’s work in Cambodia (from 1999) and Yokohama’s work in Vietnam (from 2003).

Those activities were done at the request of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, a government agency that delivers much of Japan’s ODA. But it is not easy for local governments to further extend their investments abroad because they need to get approval from their assemblies and such business activities are not something that benefit local residents.

JT: How about Japanese companies?

Takizawa: Although some companies have exported equipment and components for waterworks systems, there are no Japanese companies like the so-called water majors, such as the French-based Veolia and Suez groups that have undertaken comprehensive projects including O&M. So we discussed this at the METI panel a decade ago and suggested that collaboration between local governments and private companies should take place.

JT: How do you see progress in such public-private partnerships unfolding over the decade?

Takizawa: Efforts have been made as far as possible. For example, Kitakyushu city government has succeeded in involving local Japanese companies in water supply projects in Cambodia, while the city, thanks to research funding from JICA, continues to send experts to the country, thus collaborating with private companies in waterworks O&M on-site. The Japanese government will further encourage such practices in public-private partnerships, in which local governments are expected to support private companies and work together with them on overseas water projects.

Another potential area of business is in concession, in which a private company is granted the exclusive right to operate, maintain and carry out investment in a water utility while the local government retains ownership of the assets.

Miyagi Prefecture is scheduled to enter into a concession agreement for its water supply, sewerage and industrial water system in 2022, which will be the first water supply concession case in Japan. In March, the prefectural government chose a group of companies as the contractor. The group will have the rights to perform all O&M activities for the three water projects for 20 years.

JT: How does the concession agreement benefit the companies?

Takizawa: Having experience with concessions will qualify the companies for comprehensive overseas water projects. With long-term and large-scale O&M expertise, Japanese companies will be able to apply for overseas water projects on their own, without involving local governments.

JT: In addition to public-private partnerships, are alliances between Japanese and foreign companies growing?

Takizawa: There are many examples. For instance, one member of the group mentioned above is the Japanese subsidiary of French-based water major Veolia. Japanese companies may be able to absorb expertise in efficient O&M by collaborating with Veolia, which has extensive experience in water business.

JT: Can Japanese companies further expand business abroad by promoting advanced products with a technological advantage?

Takizawa: Again, rather than just selling products, it would be better to have a design, build, operate, transfer form of contract with the client country. In most cases of seawater desalination plants, for example, Japanese companies are appointed to operate the plant on behalf of their client countries for 20 years, in addition to designing and building before transferring O&M back to the client. This is a very stable way of business to recover their investment via operation fees at a long-term fixed rate.

JT: Please tell us about the Water Engineering and Utility Management Future Leaders Training Program at the University of Tokyo.

Takizawa: It’s a master’s degree program offered by the Department of Urban Engineering in collaboration with JICA. Starting in 2018, we began accepting five students per year from Asian countries. They are young officers at governmental institutions in charge of water systems.

The program is designed to cultivate problem-solving capacity so that students will lead the water supply sectors in their respective countries to achieve better water supply service and waterworks management. We encourage them to discuss the challenges of their countries with other students, analyze the complex issues logically and identify underlying root causes. Once the students identify the root cause, they begin to address it through field research, formulating hypotheses and testing them, and eventually propose solutions.

Although many foreign students in Japan have had difficulty going home or coming back since the beginning of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, our students were able to continue their field research thanks to JICA, which helped provide chartered flights.

A student from Indonesia discovered that seawater desalination plants, which were provided by the Indonesian government for isolated islands without water sources, do not function properly because residents don’t know how to operate the plants. As a result, islanders continue to purchase expensive tanks of water from peddlers.

We also let the students analyze the cost and revenue of their projects and how long it will take to recover the initial investment. Projects will not be sustainable if they cannot generate enough revenue to offset costs.

A student from Myanmar found out that 80% of the water meters in Yangon were broken, which reduced the fare receipts to one-fifth of what was considered reasonable for the actual amount of water residents used. The student proposed to replace the broken meters with new ones and proved that the replacements helped achieve an increase to the proper revenue, recovering the cost of the meter replacements in eight months.

In their project proposals to address water challenges, we may find some areas where Japanese technologies could be of help, and those might develop into collaborations with Japanese companies. During the five-year program scheduled with JICA, we will be able to collect 25 case studies that will be widely applicable.

JT: Finally, please share your thoughts on the future direction of water issues.

Takizawa: On one hand, water is a basic need to maintain life and health. On the other hand, we need economic rationality and advanced technologies to manage and operate the complex water systems of today. It’s important to understand both aspects. We cannot just focus on either business or assistance, but need to consider which way may be more suitable, case by case. Japan’s international cooperation and the Japanese water industry are expected to further expand projects and businesses abroad while building constructive partnerships in the next 10 years.