This is the first article in a Japan in Action series, showcasing key policies of the Suga administration.

Evenings are often the busiest time for working parents, who rush to nurseries to pick up their children and then move on to tackle endless child care tasks, from cooking dinner to bathing their children to reading them bedtime stories. Even so, they are considered lucky compared with those parents forced to put off returning to work or having to quit their jobs because they couldn’t find day care for their children.

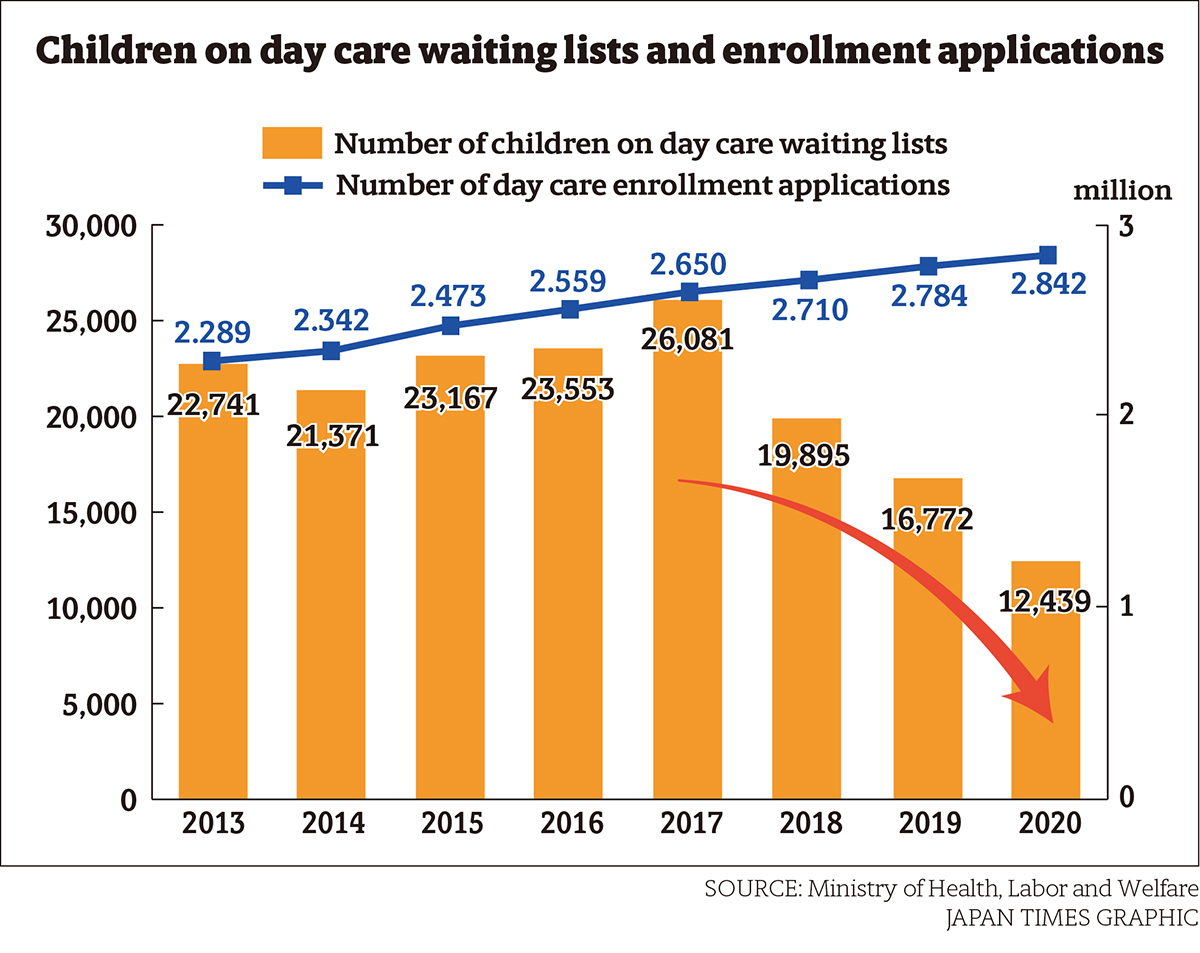

But there is some good news at hand. Long waiting lists for child care facilities, which are often blamed for Japan’s declining birthrate, are slowly but steadily shrinking, thanks to various government efforts.

The national total of children languishing on day care waiting lists hit a record low 12,439 in April 2020, thanks to the two consecutive government child care support plans implemented in the past eight years. In the past 3 1/2 years, the number more than halved from 26,081 reported in April 2017.

In the past three years alone under the previous child care support program slated to end in March this year, the government is likely to achieve its target of adding child care capacity for some 320,000 children.

To further strengthen child care support in Japan, whose total fertility rate — the average number of children a woman will bear in her lifetime — stood at 1.36 in 2019, the government will implement its new child care security plan beginning this year. The plan is part of the final report on Social Security Reform for All Generations approved by the Cabinet in December, with which the government aims to review the current social security structure of providing benefits mainly to the elderly, with the working generation taking on the burden.

Under the new four-year child care program, the government plans to boost the nation’s nursery school capacity by about 140,000 by fiscal 2024. It also seeks to reduce the number of children on nursery school waiting lists to zero as quickly as possible.

“Concerning the issue of child care waiting lists that has been a concern for many years, we will strive to achieve a final resolution by establishing child care facilities for around 140,000 children over four years while considering the projected increase in the number of women in the workforce,” Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said in the Diet during his policy speech in January. “To that end, we will fully utilize resources for child rearing, such as kindergartens and babysitters, available in local communities.”

Under this program, the government will shoulder a greater portion of construction expenses for new day care facilities.

Responding to local needs

However, the conditions facing nurseries vary from place to place. While Tokyo and other major cities in Japan are in dire need of additional child care facilities, some municipalities, for example, only need to add capacity for 10 children or so. In such cases, building an entire new child care facility may result in redundancy.

Thus, the new plan also tries to cater to demand through alternative means, such as utilizing vacant space in existing kindergartens to offer additional child care support or providing shuttle bus services to help parents take children to facilities that have capacity.

“In the past, we have focused on building new nursery schools, but the issue is no longer that simple. We will have to look at various needs in different municipalities and respond differently under the ongoing program,’’ said Yumiko Watanabe, director-general of the Child and Family Policy Bureau of the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry.

Moreover, in some municipalities, a shrinking population leaves child care facilities and nursery teachers not fully utilized. The ministry hopes to deploy these resources to provide consulting services for those who are raising children at home without using day care centers.

“Using the functions of local nurseries, we’d like to show our commitment to support all families, not just working parents, in the next four years,’’ Watanabe said.

Unutilized teachers

Another measure in the pipeline is securing nursery school teachers by tapping human resources already qualified for the job.

According to Watanabe, there are about 1.5 million licensed nursery school teachers in Japan, but only 600,000 are currently working at child care facilities.

“That means we have 900,000 licensed nursery teachers who are not working at nurseries,” she said. “How we can encourage these people to work at child care facilities could be key to solving the problem.”

But to achieve that, working conditions at child care facilities must be attractive enough to retain qualified teachers. For example, the average monthly salary of female child care workers was about ¥40,000 less than the average for all industries in 2016. Thanks to the government subsidy program, the difference has since shrunk to ¥20,000.

Other solutions under consideration include reducing their burden by utilizing more part-time nursery teachers, while easing regulations to allow assistant child care workers to work more than 30 hours a week. As the pandemic puts extra burdens on nursery school teachers, hiring additional staff to carry out miscellaneous tasks, such as sterilizing toys and cleaning rooms, is also being considered. The new plan also includes using information and communication technology to cut administrative work at facilities.

“If we can establish a society where anyone can give birth without hesitation and raise children, it would be a truly sustainable society,’’ Watanabe said, adding that baby-friendly municipalities will attract young couples to move in, helping to stop depopulation and revitalize the local economy. “It is important to create such a positive atmosphere across society.”

This series is sponsored by the government of Japan.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.